The slaves on the sugar estates – do they appear hardworked dispirited and oppressed? Open your eyes and ears to every fact connected with the actual condition of slavery everywhere – but do not talk about it – hear and [see] everything but say little.*

In 1832, Yale’s eminent scientist Benjamin Silliman advised botanist Charles Upham Shepard (Amherst Class of 1824) on how to negotiate his visit to the South, where Shepard was to investigate sugar plantations in order to assist Silliman in the production of a report to the United States government on the sugar industry. The investigation had begun in 1830 with a request from the House of Representatives to Secretary of the Treasury Samuel Ingham to “cause to be prepared a well digested Manual, containing the best practical information concerning the culture of the Sugar Cane, and the fabrication and refinement of Sugar, including the most modern improvements” (“Manual” preface). Ingham’s successor Louis McLane gave the project to Silliman, and Silliman divided it into tasks for four men, including Shepard, who went to Louisiana and Georgia, “where the sugar cane is cultivated.”

In 1832, Yale’s eminent scientist Benjamin Silliman advised botanist Charles Upham Shepard (Amherst Class of 1824) on how to negotiate his visit to the South, where Shepard was to investigate sugar plantations in order to assist Silliman in the production of a report to the United States government on the sugar industry. The investigation had begun in 1830 with a request from the House of Representatives to Secretary of the Treasury Samuel Ingham to “cause to be prepared a well digested Manual, containing the best practical information concerning the culture of the Sugar Cane, and the fabrication and refinement of Sugar, including the most modern improvements” (“Manual” preface). Ingham’s successor Louis McLane gave the project to Silliman, and Silliman divided it into tasks for four men, including Shepard, who went to Louisiana and Georgia, “where the sugar cane is cultivated.”

In his advice to Shepard quoted above on how to treat with the planters, Silliman was suggesting that he avoid antagonizing them with any kind of anti-slavery argument if he wanted the planters to cooperate with the research. Elsewhere — in correspondence between Silliman and Amherst’s President Edward Hitchcock — Silliman comes across as someone who could at once view slavery as an original sin and – from his own earlier visit to the South — observe that most of the slaves he saw were “well-treated,” simultaneous opinions that were probably typical for his time and station. We don’t know what Shepard’s views were, but it’s likely they were similar to Silliman’s.

The Charles Upham Shepard Papers contain some of Shepard’s notes and correspondence relating to “the sugar inquiry,” including several documents from planters who either answered Shepard in the form of his questionnaire or who wrote their answers in a letter. Many of these focus on the manufacture of sugar from cane, rather than on growing cane itself.

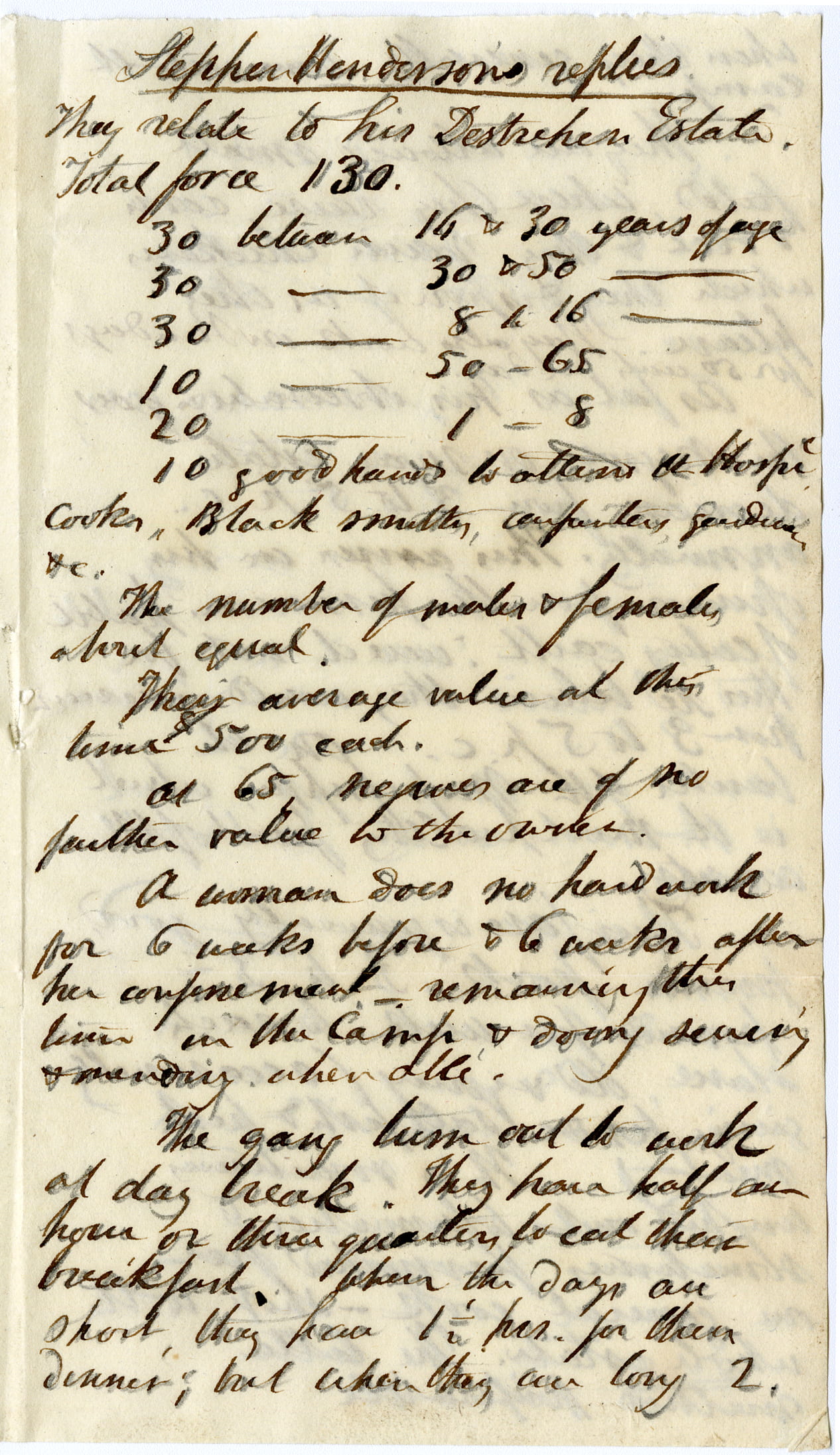

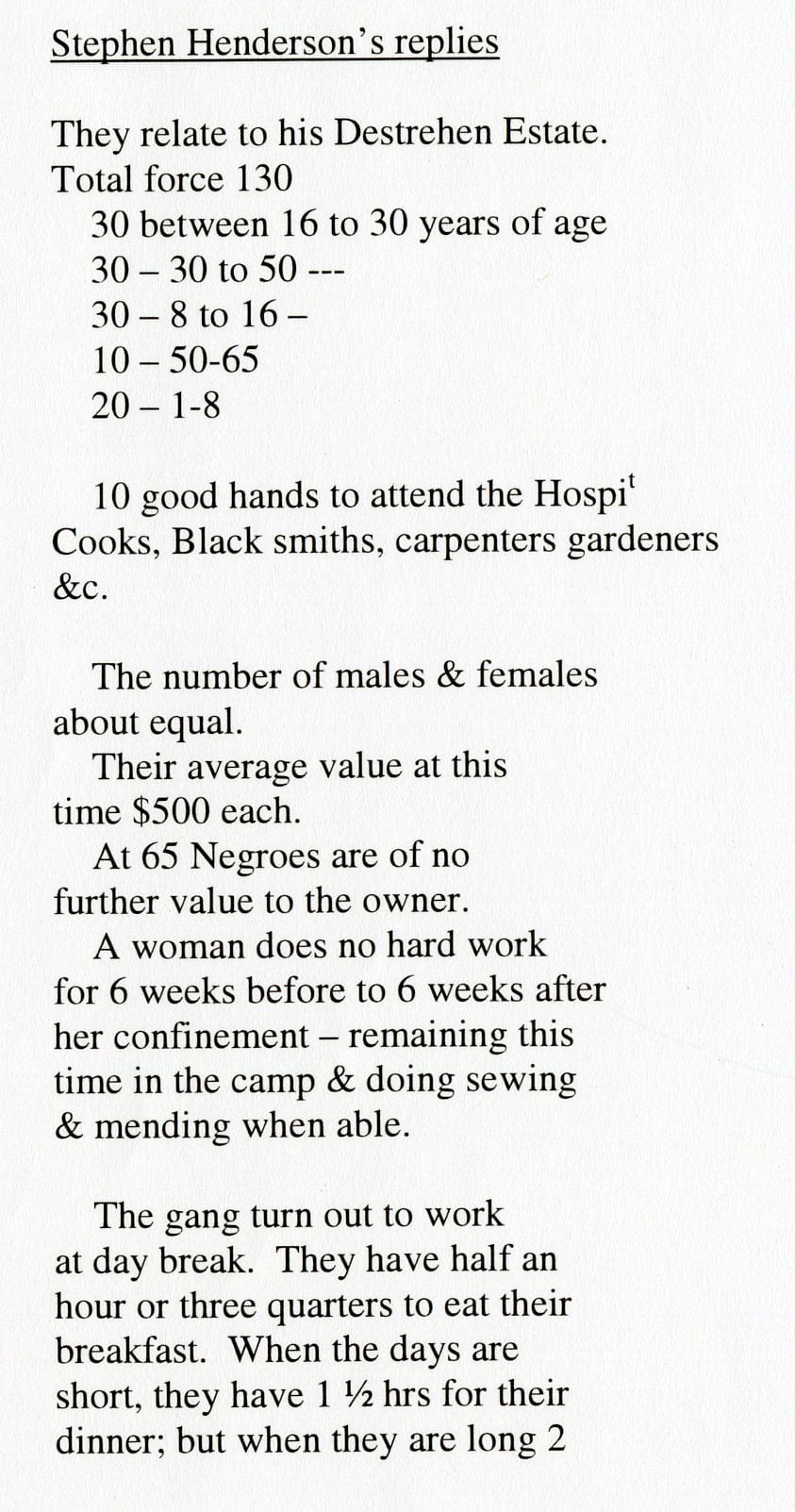

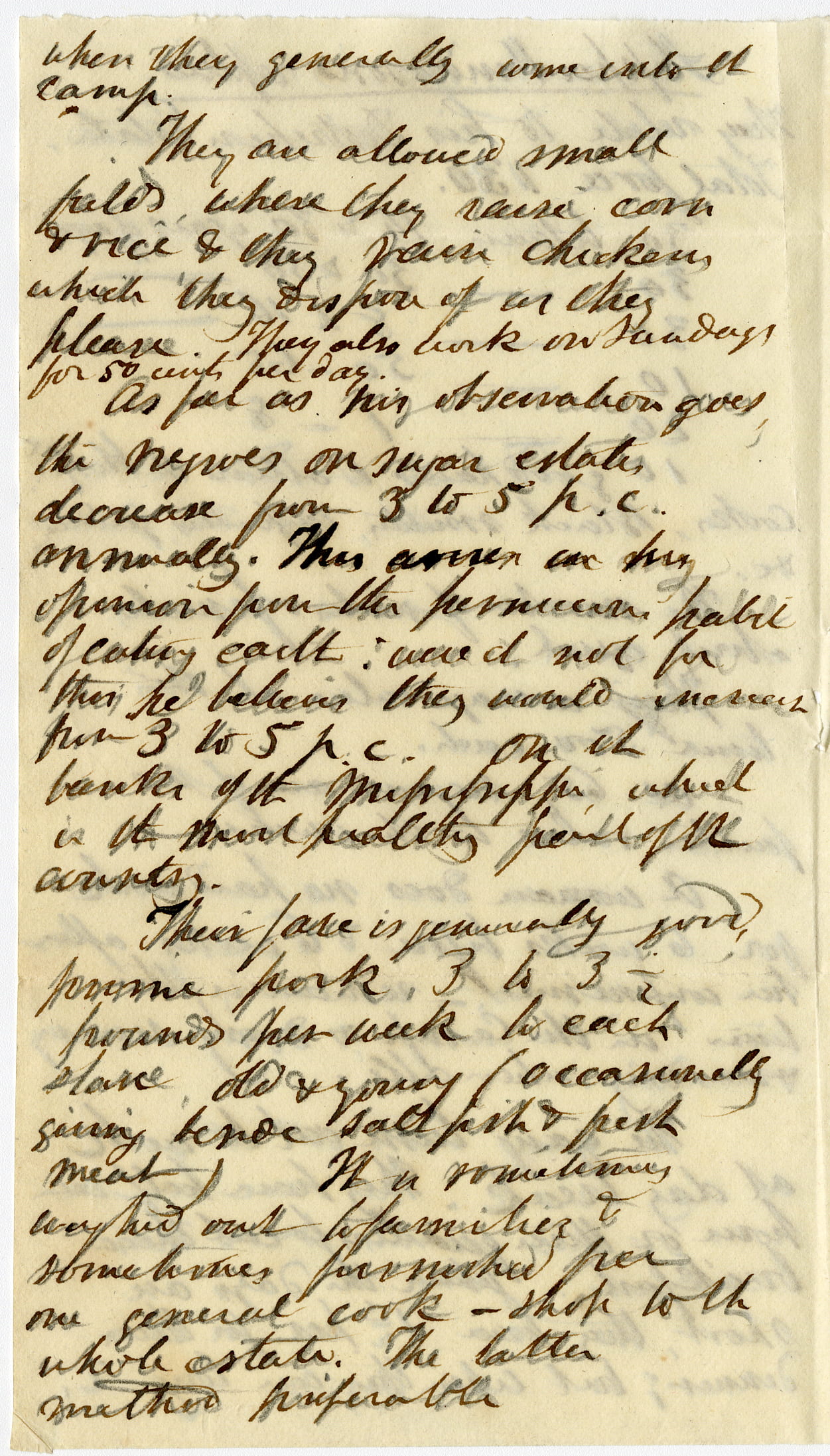

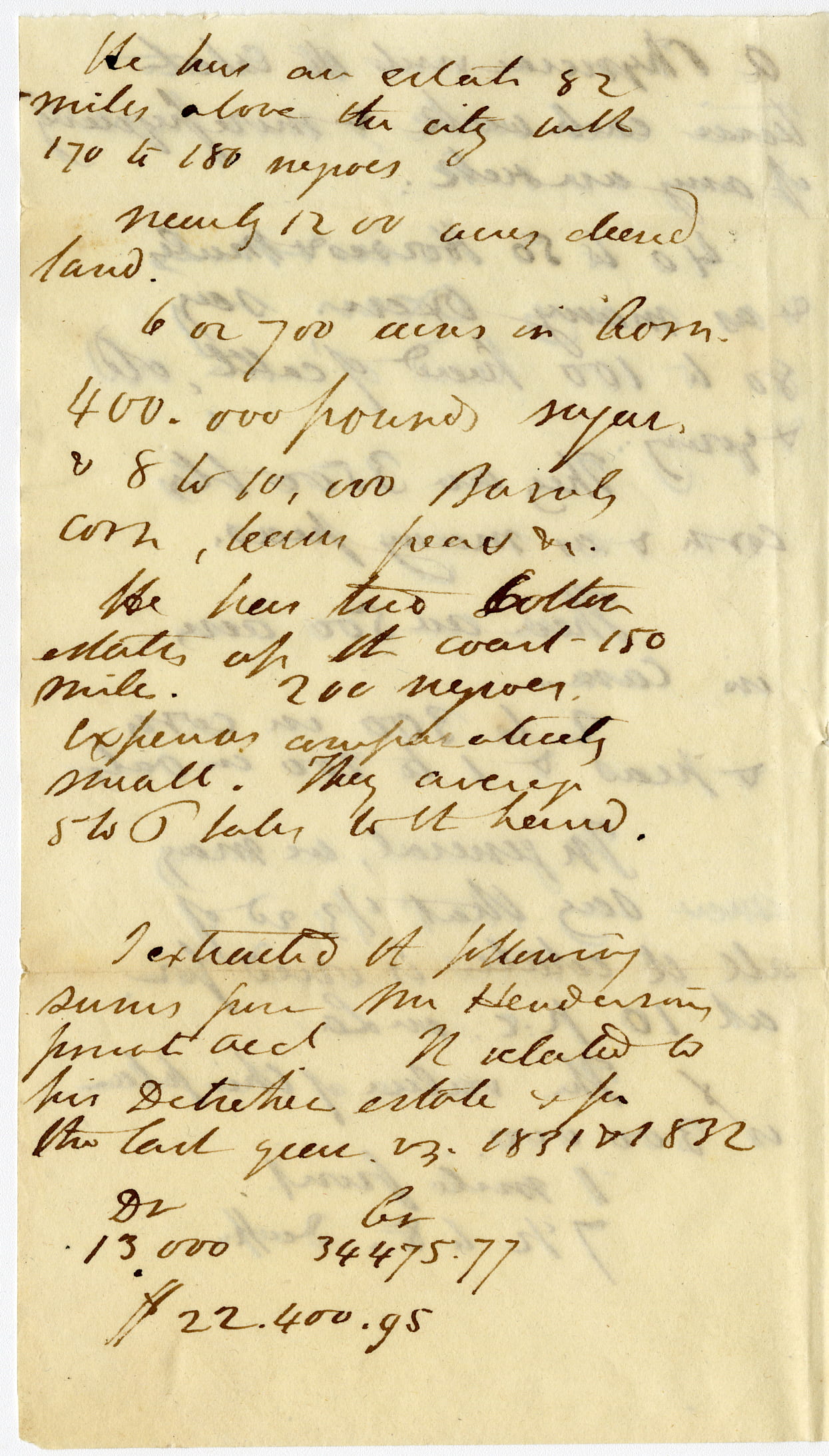

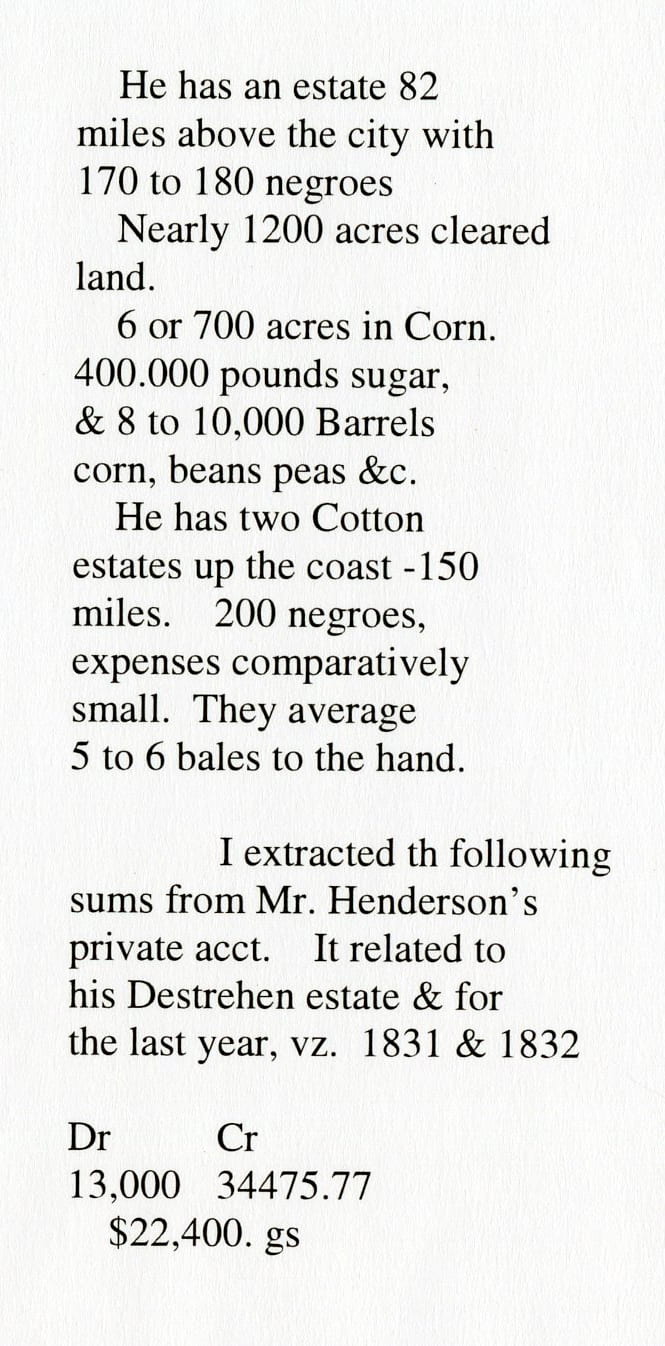

In at least one case, though, we have notes in Shepard’s hand from his conversation with a planter. The planter was Stephen Henderson, who owned several cotton and sugar plantations, including one named Destrehan, a plantation that exists as a tourist site today.

The name “Destrehan” might not have caught my eye if I had not recently watched the film “12 Years a Slave” and then read both the book from 1853 on which the film was based and a little about the making of the film.

The film includes a scene filmed in Destrehan’s “mule barn,” which was re-purposed to serve as plantation owner Edwin Epps’s cotton barn. If you’ve read “Twelve Years” or watched “12 Years,” you’ll remember that Epps is the man who enslaved Solomon Northup for ten years — he was apparently the cruelest of Northup’s many tormentors.

So, what exactly did this folded-up document that mentions Destrehan say? Here it is, including Shepard’s blurry ink-over-pencil tracing, abbreviations, and mistakes, in a sort of poisoned verse form. It’s a modest-looking document whose early 19th-century handwriting – itself dashed off probably while meeting with the planter– resists quick understanding, but transcribing it reveals sobering truths. Perhaps only Kara Walker could illustrate this text properly.

Of course, the people performing the labor described in the document above had names and identities. The document below is the first page of the registry of slaves on Henderson’s estate at the time of his death in 1838, five years after Shepard made his notes. This page shows only the first dozen of the 152 people listed on subsequent pages in the document.

Destrehan Plantation’s site has a transcription of the full list of enslaved people. The complete inventory of Henderson’s estate is available through ancestry.com or ancestrylibrary.com. See also the new National Museum of African American History and Culture for complementary material on subjects discussed in this post. The Museum opens next week, and the New York Times has published a preview featuring samples from parts of the museum.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

*”Mr. Silliman’s Instructions,” Charles Upham Shepard Papers, Box 3, Folder 5, page 4.

Thank you for sharing all this. I will have to take a slower read through it later. Very sobering-