Professor Snell.

In the tool shed.

With a piece of wood.

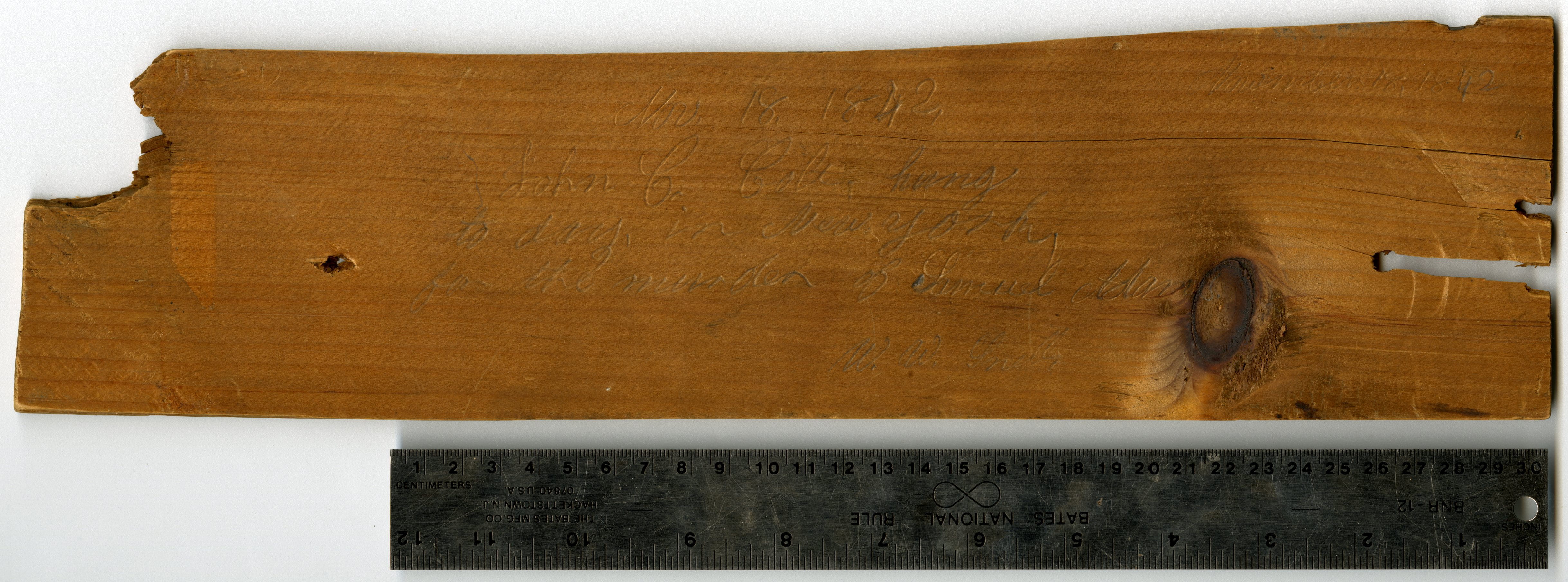

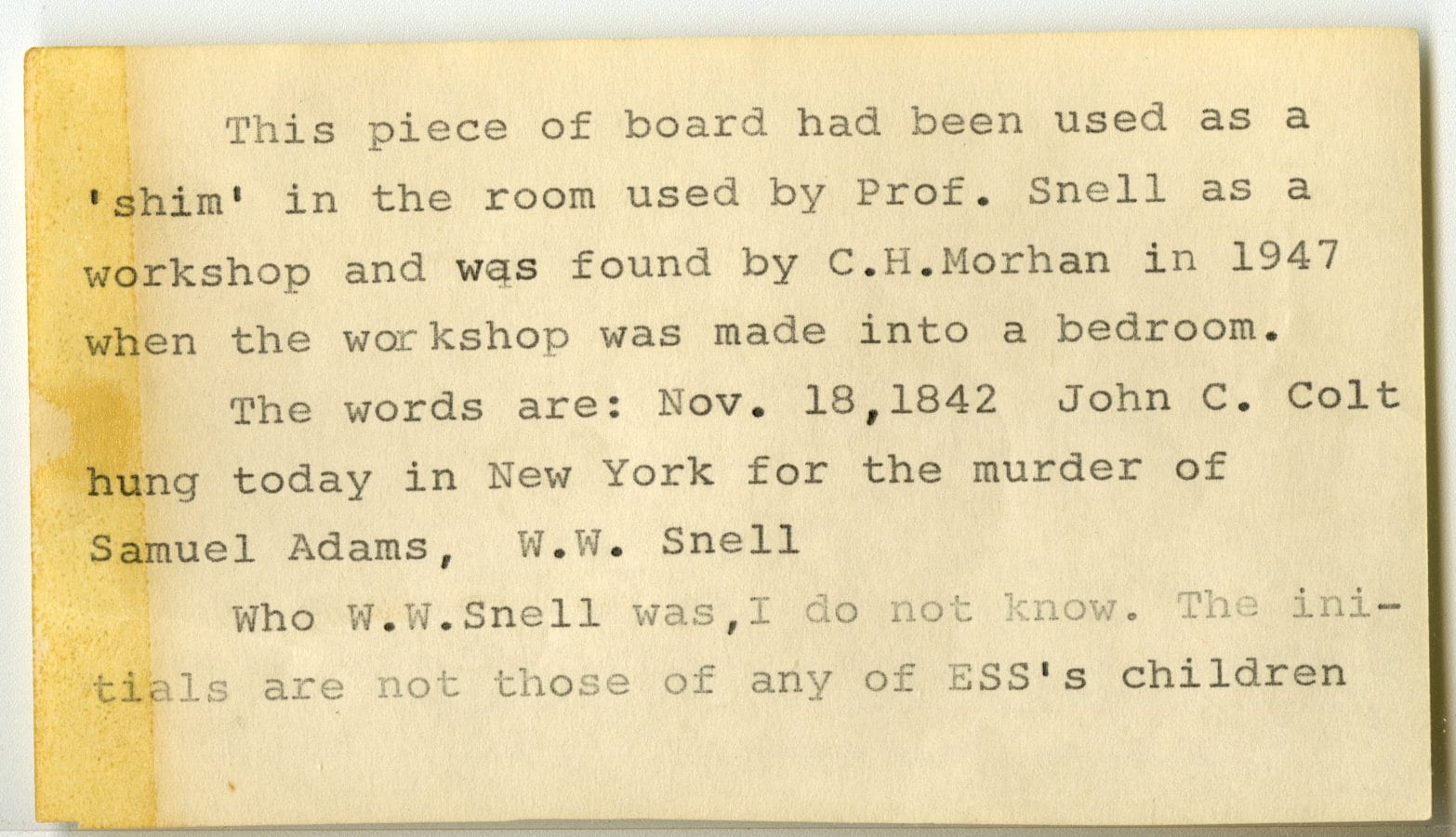

Things are already not what they seem: Prof. Ebenezer Strong Snell (1801-1876, Class of 1822) was not a murderer, a murder did not take place in his tool shed, and he used the piece of wood as a door wedge. So why does our title mention “murder,” and why would anyone save such an inconsequential-looking piece of cheap pine long enough for it to enter our archives?

The wood came to my attention some months ago when a patron asked for a document in the Snell Family Papers and the wood happened to be in the same box as the requested item. It stuck right out of the file and poked at the box lid. The file included a little card:

Apparently Prof. Charles H. Morgan (not Morhan – a typo by someone else) found the piece of wood in Snell’s house and gave it to –a guess– the archivist of the time, Peggy Hitchcock Emerson, who kept it with the rest of the Snell papers. Morgan, a professor in the Art Department, moved into the Snell house in 1932, and the information about the wood came to him from the last caretaker of the last Snell to live in the house.

The inscription raised several other questions, including “why would anyone commemorate the murder with this piece of wood, or (for that matter), any piece of wood?” and “who is W. W. Snell?

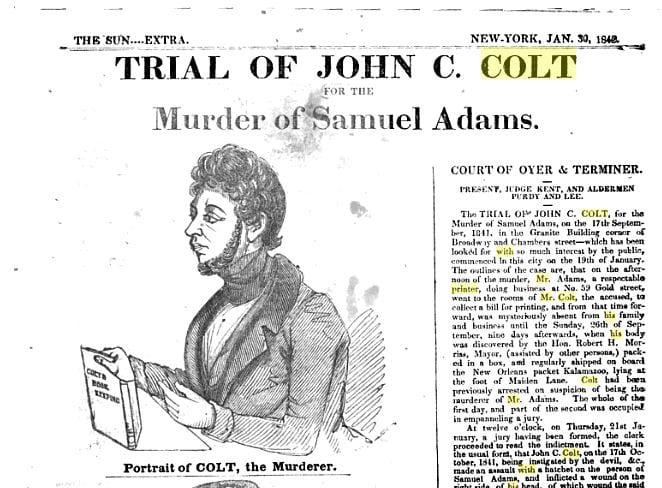

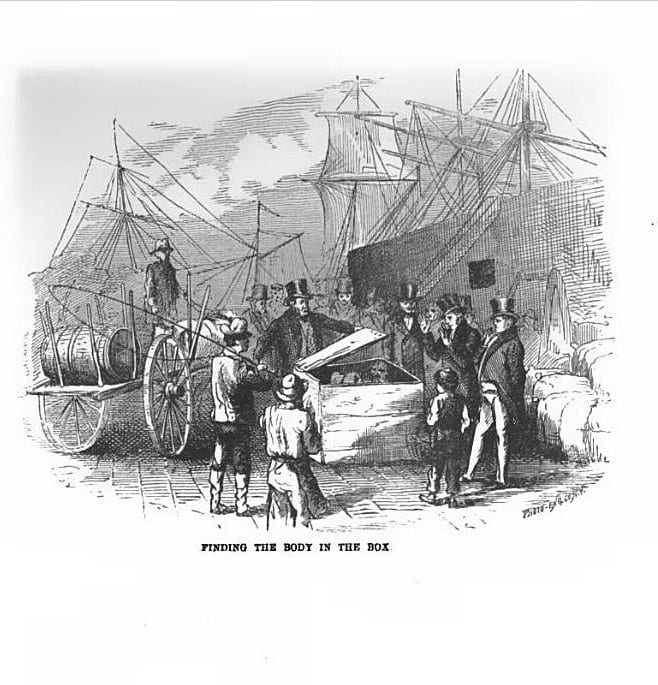

Neither Prof. Morgan nor Peggy Hitchcock had recourse to Google or to our digital newspaper archive to obtain answers. A few simple search terms with these tools brought up plenty of information about John Caldwell Colt and his sensational murder trial. Newspapers, including our local Hampshire Gazette, printed entire pages about the case and followed it from the victim Samuel Adams’ disappearance in September of 1841 to the discovery several days later of his body– stuffed in a pine box (a shipping crate) and loaded on a ship scheduled to depart for New Orleans — and then to the trial and conviction of his murderer in 1842. At its simplest, the murder was about money: John Colt owed Samuel Adams money (they disagreed on the amount) for printing Colt’s work on bookkeeping. Colt hadn’t planned to kill Adams on the day when the printer came to collect his money, but when the two argued and things went bad Colt murdered Adams with a hatchet. Colt then had to figure out how to clean up and dispose of the body quickly – hence the box in which he folded and tied the body in such a way that he could stuff it into a container that was said in court to measure 3’4″ x 1’10” x 1’9″. In Killer Colt, Harold Schechter writes that the box “had been constructed by Colt himself, who assembled all the shipping crates for his books” (p. 108), and several witnesses mention seeing this particular box as well as the equipment Colt used to make them.

Neither Prof. Morgan nor Peggy Hitchcock had recourse to Google or to our digital newspaper archive to obtain answers. A few simple search terms with these tools brought up plenty of information about John Caldwell Colt and his sensational murder trial. Newspapers, including our local Hampshire Gazette, printed entire pages about the case and followed it from the victim Samuel Adams’ disappearance in September of 1841 to the discovery several days later of his body– stuffed in a pine box (a shipping crate) and loaded on a ship scheduled to depart for New Orleans — and then to the trial and conviction of his murderer in 1842. At its simplest, the murder was about money: John Colt owed Samuel Adams money (they disagreed on the amount) for printing Colt’s work on bookkeeping. Colt hadn’t planned to kill Adams on the day when the printer came to collect his money, but when the two argued and things went bad Colt murdered Adams with a hatchet. Colt then had to figure out how to clean up and dispose of the body quickly – hence the box in which he folded and tied the body in such a way that he could stuff it into a container that was said in court to measure 3’4″ x 1’10” x 1’9″. In Killer Colt, Harold Schechter writes that the box “had been constructed by Colt himself, who assembled all the shipping crates for his books” (p. 108), and several witnesses mention seeing this particular box as well as the equipment Colt used to make them.

He got the box downstairs (not too big a box, not too big a body) and paid someone to help him get it to the wharf.

If the ship had departed with the body on board, Colt might have gotten away with it. In fact, given that it took a week for keyhole witnesses (literally) to get the authorities’ attention, it’s a wonder he didn’t get away with it. He was so close. But things continued to go awry for Colt (not to mention Adams), and the ship didn’t leave on time. Soon the contents began to smell. The police, already alerted to the disappearance of Adams, came and pried the lid off the box.

From here events followed swiftly – the victim was identified, the suspected murderer was arrested, and the evidence was hauled away. Including the box.

This much was clear and, in its way, straightforward and well documented. But still: why would Professor Snell have this piece of wood with such an inscription? The answer (according to my theory) is in details from the small world that was Western Massachusetts in the early 19th century.

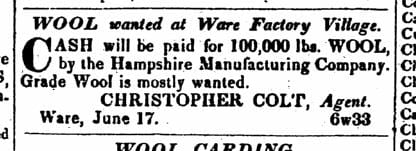

If the reader hasn’t already made the connection, murderer John Colt was the brother of repeating firearms inventor Samuel Colt. In the late 1820s and into the 1830s their father, Christopher Colt, worked at a textile mill in Ware, Massachusetts, where John and Samuel spent at least a little time (mostly coming and going quickly) and where Sam acquired notoriety on July 4, 1829, by blowing up a raft on Ware Pond. On that occasion things didn’t go quite as he planned (apparently a Colt family tradition) and the explosion drenched the villagers who’d gathered to witness the event. The villagers were angry and Sam barely escaped punishment.

If the reader hasn’t already made the connection, murderer John Colt was the brother of repeating firearms inventor Samuel Colt. In the late 1820s and into the 1830s their father, Christopher Colt, worked at a textile mill in Ware, Massachusetts, where John and Samuel spent at least a little time (mostly coming and going quickly) and where Sam acquired notoriety on July 4, 1829, by blowing up a raft on Ware Pond. On that occasion things didn’t go quite as he planned (apparently a Colt family tradition) and the explosion drenched the villagers who’d gathered to witness the event. The villagers were angry and Sam barely escaped punishment.

The town of Ware is right next to Brookfield, where Ebenezer Snell’s family lived (specifically in North Brookfield), so it’s very possible that the Snells heard about the Ware Pond event, as well as about the mysterious explosions in the woods around town that the villagers came to suspect were Colt’s doing.

Not too long after the pond incident, Samuel Colt was hustled off to Amherst Academy (or perhaps “back” — it’s unclear when he first attended the school). If Ebenezer Snell didn’t know about Sam Colt from the latter’s days in Ware, he certainly came to know him in Amherst. Snell had attended Amherst Academy himself and taught there later (1822-25). By the time Colt got there, Snell was a professor at Amherst College, just a block away. Although we don’t know for sure when Colt arrived in Amherst, we know when he left: shortly after July 4, 1830, when Colt and classmate Robert Purvis* stole Ebenezer Mattoon’s Revolutionary War cannon (a weapon with a long history of town escapades), dragged it up to the Amherst College campus, and scared the frocks off students and professors. A newspaper comment from a few weeks later and a diary entry from the following year document the occasion and the excessive “huzzaing”:

![Excerpt from the journal of J. A. Cary, Class of 1832. This entry from July 3, 1831: …The day tomorrow is to be [observed] by religious exercises. Our last anniversary will long stand recorded in the annals of Hell, & may this be as long remembered in the records of Heaven. Last year the “consecrated eminence” was surrounded by the mists & fogs of the region of darkness, but in this it has been refreshed by the dews of heaven. A year since & the roar of artillery, I doubt not, & the cheers & shouts of the ungodly were echoing and reechoing from the dark caverns below, in this many of those same voices are lifted up to God in praise, and in “humble grateful prayer.”](https://consecratedeminence.wordpress.amherst.edu/files/2015/06/1832-cary-ja-jrnl-excerpt-1831-jul-3-crppd-re1830-jul-41.jpg?w=300)

Amherst July 22, 1864

Hon. Henry Barnard

My dear Sir,

Your letter of yesterday is just rec’d. I well recollect the main incidents of the celebration enquired about; tho’ I never before knew that the celebrated Hartford Sam. Colt, was the hero of that occasion.

A young wild fellow of the name of Colt of Ware, was a member of our Academy & joined with other boys of Academy Lodge, on College Hill, in firing cannon, early in morning of 4th July. (The day of the week, I can’t tell.)

Some of the officers of College interfered & tried to stop the noise. Colt, as Prof. Fisk [probably Professor Nathan Welby Fiske, father of Helen Hunt Jackson] ordered him not to fire again, and placing himself, as the story was told, the next day near the mouth of the gun, swung his match, & cried out, “a gun for Prof. Fiske.” & touched it off – the Prof. enquired his name – & he replied, “his name was Colt, & he could Kick like Hell” – He soon left town, for good. This was the account given at the time – & has after been repeated here.

I met Prof. Snell, directly after receiving your letter, and as he was here, at the time, I enquired of him about it. He recollects Prof. Fiske relating to him, the [instance? i.e. “story” or “occasion”] of his being on the ground, & saying that the [instance?] started by some of the boys, that he, Prof. Fiske, tried to straddle the gun, was not true. So, I think I have given you about as it was. I am always happy to hear from you, & to meet you. With kind regard & esteem, I am very truly yours, Edward Dickinson.”

So when in 1841-2 the Snells read of the trial of John Colt for the murder of Samuel Adams, they would have had personal memories of the Colt family, both because of Sam Colt’s notoriety in Amherst and because of the proximity of the Snell and Colt families in neighboring towns.** And there was yet another reason the murder would’ve shocked them: they knew the victim, probably very well.

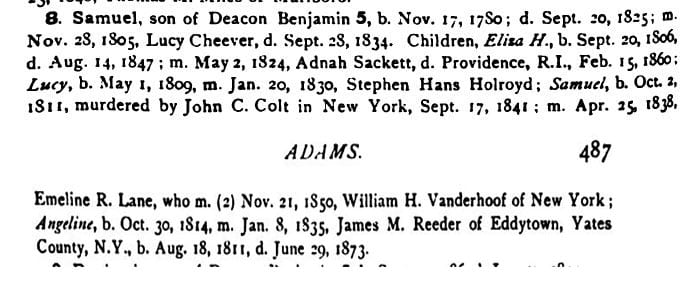

According to the “History of North Brookfield,” Samuel Adams, John Colt’s victim, was also from North Brookfield. He appears just before “ADAMS” in the center of the image below.***

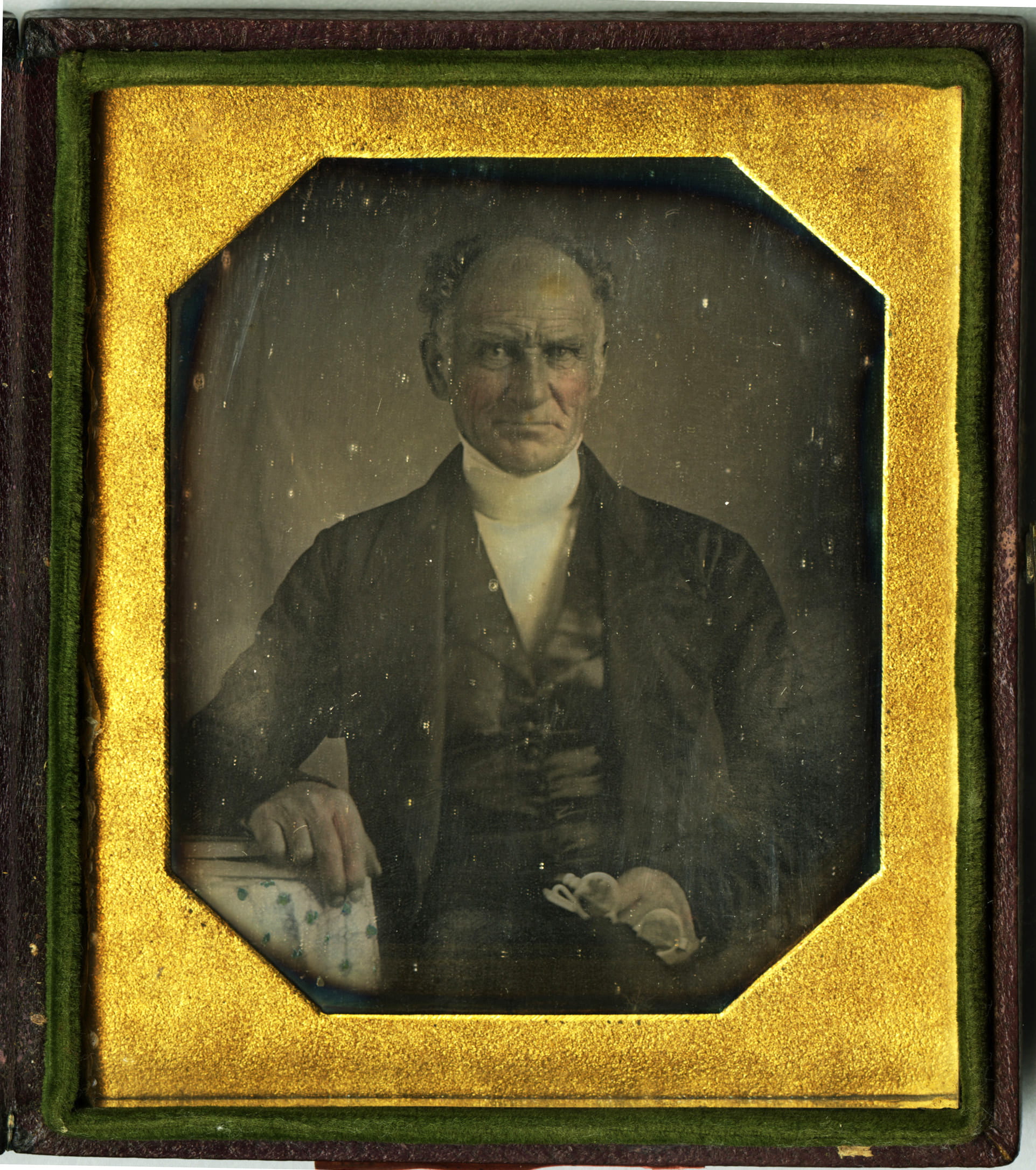

The Snell family knew the Adams family because Rev. Thomas Snell, Ebenezer’s father, led the church in town for 64 years, from 1798-1862, and Benjamin Adams, Samuel’s grandfather (d. 1829), was a deacon in the same church. Thomas Snell said of Benjamin Adams, “At the time of my settlement, no member of the church had so much influence in ecclesiastical affairs as Dea. Adams. He was a good judge of preaching, and a man of uncommon attainments for one who enjoyed no greater advantages. At this time he was the only member of the church who would take part in a religious meeting” (History of North Brookfield, page 485). Benjamin’s grandson Samuel was also in the same age group as some of Ebenezer’s younger siblings, so they may have played or been in school and church together. The “W. W. Snell” — William Ward Snell — of the inscription on the wood was born in 1821, so to him Samuel Adams would’ve been an older boy by a decade.

But let’s get back to that piece of wood in the Snell Family Papers. What is this piece of wood?

Accounts of the trial of John Colt reveal that the lid of the pine box containing Adams’ body went missing:

In court testimony about the missing lid a police officer remembered that the prison watchman had offered to show him the box. The officer’s testimony “suggested that at least one man with access to the lid — Watchman Patrick — understood its value as a curio” (Schechter, p 178). Later, however, another watchman said that he had used the lid to build a fire on a particularly chilly night. He offered the helpful (if suspiciously superfluous) detail that the lid had smelled “strong” when it was burned (Schechter, p.184). Either way, the lid was gone, apparently for good.

Given the relationship between the Snells and those involved in the case (the Colt and Adams families), I wonder, then, whether the piece of wood that one Snell inscribed and another kept and used as a wedge for decades is in fact a piece of the missing lid. I think that Ebenezer’s brother William Ward Snell somehow came into possession of that piece of wood, possibly through a member of the Adams family or a mutual connection of the Colts and the Snells. In 1842, William Snell was a young man of 21 or 22 perhaps fascinated by a murder trial involving a victim he knew personally. Like whoever took the lid, probably dividing it into several pieces, Snell would’ve viewed the segment as a souvenir of the crime or a memorial of the victim. But why does it appear among brother Ebenezer’s possessions? I can’t answer that question (yet), but I do at least know that brother William moved out west and may have left some of his possessions behind, and I know too that Ebenezer himself wasn’t above a bit of rubbernecking at murder. His memoir of a trip in August of 1827 reveals that he witnessed the hanging (a botched one, apparently) of Jesse Strang for the murder of John Whipple — the “Cherry Hill murder”:

If you look closely at the piece of wood, you can still see the nail holes where the piece was tacked down. In Colt’s confession he describes how the box originally had only a few nails, not enough to keep a body secure, so he purchased additional nails and then stood on top of the box to force the body into its tidy package: “I had to stand on [Adams’ knees] with all my weight before I could get them down. I then nailed down the cover.” (Edwards, Story of Colt’s Revolver, p 169; reprinted from Colt’s confession in “Authentic Life of John C. Colt”).

From one day to the next, you never know what you’ll find in the archives.

_________________________________

* Contrary to the information on his current Wikipedia page and other sites, abolitionist Robert Purvis didn’t attend or graduate from Amherst College, he attended Amherst Academy. The two schools are often confused. However, students at the Academy were allowed to attend lectures at the College, so it’s quite possible that Purvis attended lectures here.

** Research for the 2018 post “A Strength of Snells” revealed that in fact two Snell in-laws, Moses Porter and Lucretia Colt Porter, were first cousins of John and Sam Colt. This relationship would’ve brought the Colt murder case right into the Snell family parlor.

*** Newspaper accounts of the case put Samuel Adams in Providence, Rhode Island, but he may have gone there to begin his career, perhaps through connections with his older sister Eliza Sackett, who lived in Providence.

Reblogged this on O LADO ESCURO DA LUA.

That Pittsfielder, Herman Melville, discusses the case in Bartleby the Scrivener. I could give you the quotation, but I prefer not to.

The photo of Rev. Thomas was taken by his son, William Ward Snell. The original is on a glass cube etched with metal- I was told it is earlier than an ambrotype- not sure what to call it.

Hi, Susan — The original I included here is in the Archives and Special Collections and it’s a daguerreotype. I replaced the glass and resealed it when I was writing this post.