I am currently putting the finishing touches on our new exhibition: Race & Rebellion at Amherst College. This exhibition explores the history of student activism and issues of race, beginning with the founding of the Anti-Slavery Society in 1833 and the “Gorham Rebellion” of 1837 through the takeover of campus buildings by black student activists in the 1970s. No exhibition on a subject as broad and complicated as race can ever claim to be truly comprehensive and all-inclusive. This exhibition focuses on recovering the deeper history of African-American lives at Amherst College between 1826 and the late 1970s; we could just as easily have mounted an entire exhibition about more recent events of the last 25 – 50 years.

Two books about Amherst’s black alumni have been published: Black Men of Amherst (1976) by Harold Wade, Jr. and Black Women of Amherst College (1999) by Mavis Campbell. Both of these books need to be revised and brought up to date. One theme in the exhibition is the recovery of black lives at the college that were not included in either published volume. In some cases, we have identified African-American students who graduated from Amherst in the 19th century who were not included in Black Men of Amherst, but there are entire categories of people who were intentionally left out of both books.

The first category is that of service staff at the college. Charles Thompson, for example, was born in Portland, Maine in 1838, spent some time in Boston then worked on three long sea voyages before returning to Boston to work as a coachman. Sometime in 1856 or 1857, Charles Thompson came to work at Amherst College, where he spent the rest of his life in service.

As fraternities began to build and manage their own houses in the 1870s and 1880s, many employed black servants.

The solitary black figure at the back of this group portrait of the members of Beta Theta Pi fraternity in 1890 is identified as “Olmstead Smith ‘The Dark’” on the back of this photograph. The large feather duster in his hand emphasizes Smith’s position as the fraternity custodian.

This fraternity group portrait also includes a single African-American, Perry Roberts. Perry Roberts served as the custodian for Delta Upsilon from approximately 1882 until the early twentieth century. Delta Upsilon group photos regularly show Roberts seated front and center holding the fraternity seal.

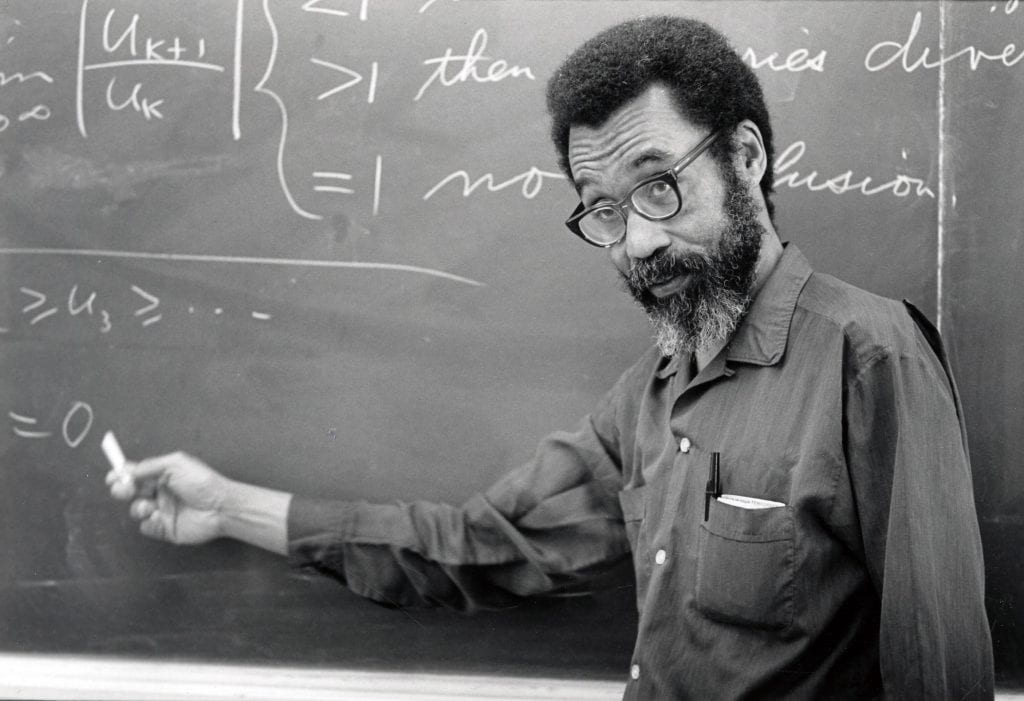

Although Edward Jones was the first African-American to graduate from Amherst back in 1826, it wasn’t until 1964 that the college hired its first black faculty member. Professor James Q. Denton taught mathematics and statistics at Amherst until his retirement in 2005.

Poet, activist, and scholar Sonia Sanchez was the first African-American woman to join the faculty at Amherst College. She arrived as a visiting assistant professor in 1972 and left for a position at Temple University in 1975.

Professor Sanchez was soon followed by Andrea Rushing who was hired in 1974 to teach Black Studies and English. She retired in 2010.

Mavis Campbell, author of Black Women of Amherst College, came to campus in 1976 to teach Black Studies and History. She retired in 2006.

These names and faces just scratch the surface of the multiple lives of people of color at Amherst College. In this exhibition we have chosen to focus specifically on African-American individuals, but we encourage others to use the resources of the Archives to explore other minority groups and their experiences at the college.

Reblogged this on tubibloginformatico and commented:

Good job!

This is just so great!

Thank you for this interesting post about Black people at Amherst College. There were few African American students at Amherst in the years I was there. But I believe in 1959 or 1960, I attended a meeting to hear a speech by Benjamin J. Davis, Jr., class of 1929. He was hosted during this return to his alma mater by biology professor, Tom Yost. Benjamin Davis had just been released from prison after serving four years at Terre-Haute Penitentiary, railroaded because he was a member of the Communist Party USA. He should be honored and celebrated for his courageous stand against the atrocious Smith Act later overturned by the U.S.Supreme Court as un-Constitutional. The “Big Lie” was that Ben Davis and 11 other Communist Party members had “conspired to teach and advocate the violent overthrow of the United States Government.” What a flagrant falsehood! Ben Davis was a kind and gentle person elected and reelected repeatedly as a City Councilman of New York City representing Harlem. Ben Davis joined the CPUSA while serving as the attorney fighting the lynch-law frame-up of Angelo Herndon in Atlanta. Herndon had been accused of “insurrection” for daring to organize white and African American workers into the Unemployed Councils during the Great Depression. In those days the CPUSA’s main slogans were “Organize or Starve” and “Black and white Unite! Same Class, Same Fight.” No wonder the offspring of the slaveowners who controlled Atlanta and Georgia were trembling in fear at this “insurrection.” Black and white together? Victory in that struggle would mean the end of segregation. I don’t have Harold Wades’ book to see if he includes a chapter—or two—about Benjamin J. Davis, Jr. But I would be willing to bet he DOES! If Wade did not include Ben Davis, I very much agree his book needs to be updated. Tim Wheeler, Amherst College, Class of 1964.