Towards the end of last semester, it was time for me to begin thinking of a topic for my final paper in a course I was enrolled in, “Sex, Gender, and the Body in South Asian History.” Over the course of the semester, the course, taught by Professor Mekhola Gomes, equally explored a range of primary and secondary sources to better grasp how the quotidian concepts of “sex,” “gender,” and “body,” can be examined in the context of South Asian history.

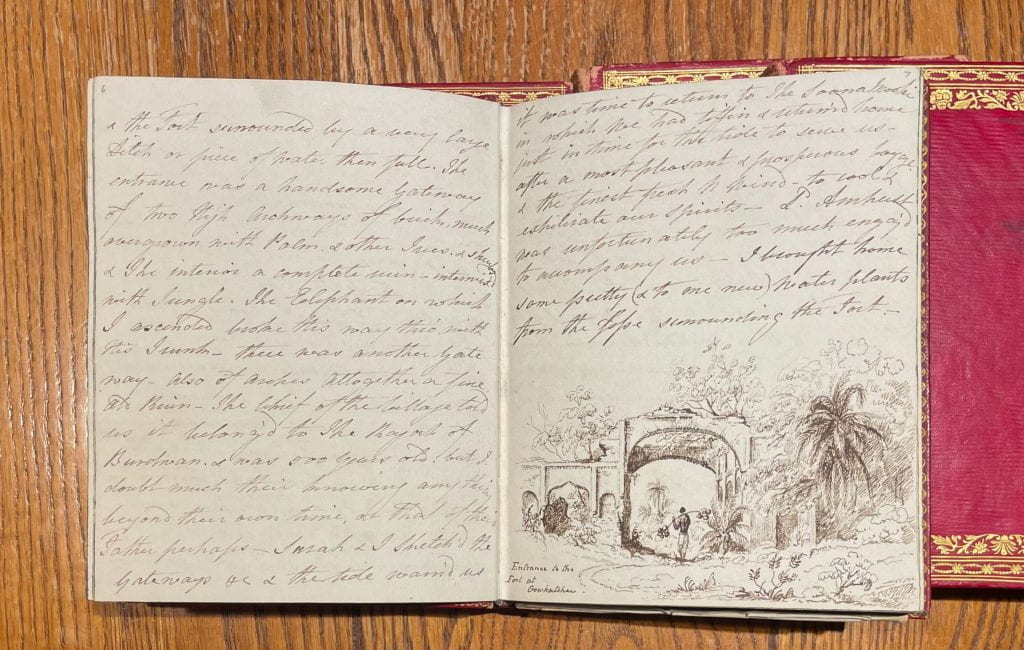

I instantly thought back to when I found out about the William Pitt Amherst Family Collection, specifically the diaries of Sarah Archer Amherst, while working in the Amherst College Archives and Special Collections. I was interested in writing about sati – the practice of widow burning – which was abolished in India in 1825 by the British colonial government. Lady Sarah Amherst, the wife of William Pitt Amherst, Governor General of India from 1823 to 1829, documented her time as a colonial wife in seven 200-page volumes that capture her day-to-day activities living in India. I wanted to know: did Lady Amherst ever produce accounts of sati? And if so, what did these accounts look like?

I came with these questions to the archives, this time as a patron, and began looking through the diaries. Instantly, I felt deep despair. In my hands were these diaries from more than two hundred years ago that detailed the life of a colonial woman living in India as the wife of the Governor General, and I could not read a single word. At that moment I realized the significant gap in knowledge for young researchers, like myself, who cannot read cursive. Part of me wanted to give up right away, trying to decipher Lady Amherst’s handwriting almost felt like reading a foreign language; however, I knew how critical of a skill this would be for me as a historian and as someone who is deeply interested in learning about the past.

Luckily for me, as a worker at the Archives myself, I knew who to approach and within the next couple of days with the help of Mimi Dakin, I was spending small chunks of my evening tracing cursive handwriting in a children’s penmanship book. It was difficult and I was frustrated. But I realized, when I came back to the Sarah Archer diaries a week later, the foreign words appeared more legible!

As I browsed through the diaries looking for answers to the questions I had come with to the archives, I came across multiple accounts of sati noted by Lady Amherst, which seemed to reproduce formulaic male descriptions of the practice. It was difficult to ascertain whether Lady Amherst witnessed the satis herself; however, her descriptions of the practice conformed to the traits of those produced by colonial men at the time. Historian Lata Mani is critical of accounts like Lady Amherst’s, which she argues exemplifies how violence against Hindu women was normalized, and religion was used as an imperative in justifying the inherently violent instances of immolation, as it was seen to have the force of nature.

As I worked with these diaries in the spring, I recognized that these diaries were invaluable sources documenting the events and culture of Indian society in the early 19th century. The finding aid at the time lacked a detailed account for the rich history documented over the seven volumes. Over the course of the summer, I read all seven volumes in an attempt to enhance the descriptions of the volumes. This was a rewarding experience: not only did I learn greatly about Indian society at the time and the life of colonial officials, but I also significantly improved my ability to read her handwriting.

Simultaneous to reading Lady Amherst’s diaries, I was creating a LibGuide that would help others like me learn how to read old handwriting. This LibGuide includes pages from various documents found in the Amherst College Archives and Special Collections and their transcriptions, including Edward Hitchcock’s personal notebooks, Theodore Baird’s diaries, and Amherst College Faculty’s administrative records books, all from the 19th and 20th centuries. As I was compiling the documents, I realized that learning how to read old handwriting had opened up so many doors for me! I hope that the LibGuide can help others the same way.

A link to the guide: https://libguides.amherst.edu/c.php?g=1340654&p=9883151.

You must be logged in to post a comment.