Every new film that tells a story about Emily Dickinson seems to stir up a new round of questions about her life and writing. In 2016 it was A Quiet Passion, directed by Terence Davies and starring Cynthia Nixon as the adult Dickinson; in 2019 it’s Wild Nights with Emily (2018) directed by Madeleine Olnek with Molly Shannon playing Dickinson. While we normally steer clear of debates about the accuracy and merits of fictional portrayals of Dickinson, a recent interview with Molly Shannon calls for some clarification of the facts.

In this televised interview that aired in early April 2019, Molly Shannon makes the following claim around the 1:05 mark:

It’s really cool … there were these erasures found in her work through spectrographic technology where they can find all this stuff about great historical figures…

While a single interview on a morning talk show may not seem like much, we want to correct the record to state that none of the Emily Dickinson manuscripts held at Amherst College have undergone any sort of analysis via “spectrographic technology” or any kind of imaging beyond a visible-spectrum flatbed scanner.

Amherst College launched Amherst College Digital Collections in the fall of 2012 and made full-color scans of all of our Dickinson manuscripts freely available online in early January 2013.

At that time, our goal was to make these manuscript images as widely accessible as possible. People interested in Dickinson’s life and poetry no longer had to trust the word of scholars with the resources and expertise to visit the special collections at Amherst and Harvard; they could see the manuscripts for themselves.

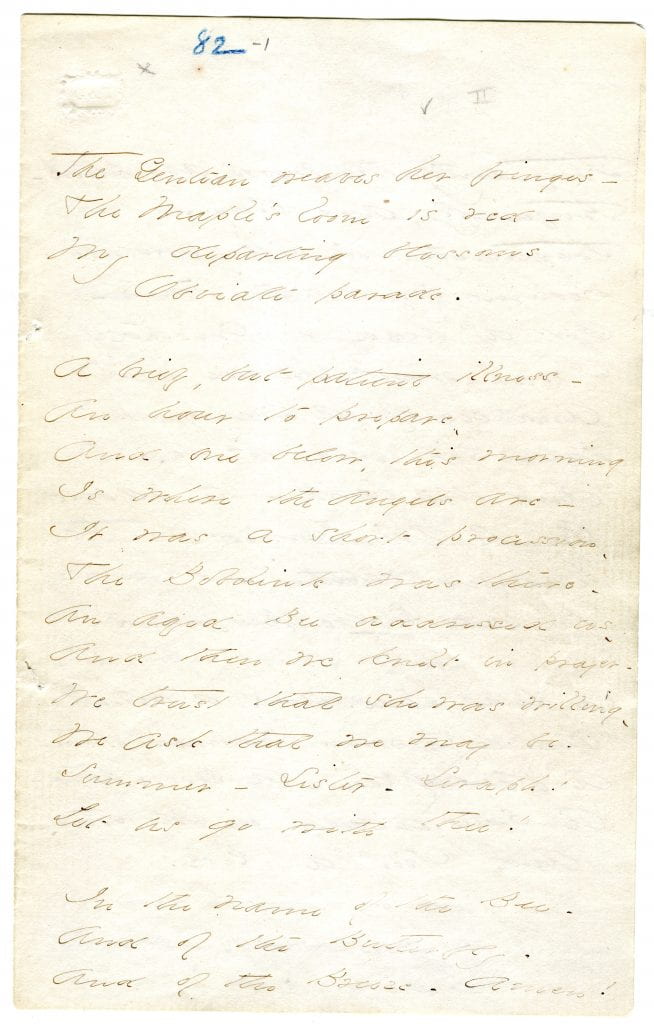

The first facsimile of a Dickinson manuscript we have been able to locate is the “Fac-simile of ‘Renunciation,’ by Emily Dickinson” that appeared at the front of Poems: Second Series edited by Mabel Loomis Todd and Thomas Wentworth Higginson and published by Roberts Brothers of Boston in 1891.

Prior to the widespread adoption of digital photography in the early 21st century, producing photographic facsimiles of important manuscripts was far more difficult. Ralph Franklin’s 1981 two-volume set The Manuscript Books of Emily Dickinson was a major achievement of editorial scholarship and facsimile publication.

The reproductive technologies of the time made it cost-prohibitive to publish the facsimile images in full color, but these black and white images were a great leap forward.

Today anyone with an internet connection can see a better quality image of this same manuscript via ACDC: https://acdc.amherst.edu/explore/asc:15595/asc:15597

Within ACDC, users can download their own copy of the image or use the built-in tools to zoom in and rotate the image. As much of an improvement as these color scans are, there is more work to be done. First, it’s important to recognize that these scans were created before Amherst College had established a formal Digital Programs department with dedicated imaging professionals. The Archives & Special Collections staff used a standard flatbed scanner that captures only visible-spectrum light to create 600dpi master files back in 2008-2009. These same master files are what is in ACDC today.

In the meantime, advances in imaging manuscripts have been going on all around us. Perhaps the most famous example of using new technology to recover a lost text is the Archimedes Palimpsest. As described on their website:

The Multispectral Imaging of the Archimedes palimpsest was undertaken by Keith Knox, of the Boeing Corporation based in Maui, William A. Christens-Barry of Equipoise Imaging LLC, and Roger Easton, Professor of Imaging Science at RIT. … To explain multispectral imaging, we must make a short digression into electromagnetic radiation…

Those interested in the science of multispectral imaging can find out much more on the Archimedes Palimpsest site, but the point is that such imaging is complex and requires carefully calibrated equipment to produce reliable results.

Perhaps no facility better captures the excitement of using new technologies to study the material culture of the past than the Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage at Yale University. This Yale news story about their work on their “Vinland Map” describes some of the imaging techniques and technologies that were not available just 10 or 15 years ago: Yale putting high-tech tests to its controversial Vinland Map.

We don’t mean to fault a Hollywood actress for not knowing the full details of the history of the digitization of Dickinson manuscripts; she is not a professional scholar of Dickinson or material culture. We do feel the need to state, for the public record, that none of Amherst’s Dickinson manuscripts have undergone multispectral imaging of the sort now available at Yale.

While Amherst does not have the capacity to do the sort of imaging done at the Yale IPCH, technical details of their processes are readily available online: https://digitalcollections.wordpress.amherst.edu/about/ As interest in the deeper physical features of Dickinson’s manuscripts gains public attention, we have begun exploring ways we might use the newest technologies to improve our scans to better serve the public.

This review of the film WILD NIGHTS by Joanne Laurier and David Walsh is also highly relevant: https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2019/05/10/wild-m10.html