In early 2017 I posted about 25 individual daguerreotypes from the Amherst College Class of 1850 that are part of the Archives and Special Collections. I provided new glass for each daguerreotype, reassembled each unit, and attempted to identify the members of the class. The daguerreotypes were in envelopes, having been removed in the 1980s from a grouping in an old wooden frame, which was apparently discarded. With only two exceptions – Austin Dickinson and George Gould – there were no names attached to the daguerreotypes from a class well known to Emily Dickinson, who often mentioned Austin’s classmates in her letters. The identifications I proposed in the 2017 post were based in particular on things like a visible fraternity pin in a daguerreotype that could be compared against a list of known fraternity members, or later images of the students that could be compared with their youthful ones. In this way, it was possible to identify everyone at least tentatively. And there the matter rested.

A few months later I needed to write a thank-you note to someone who gave us a collection of daguerreotypes by Professor Ebenezer Snell’s brother William Ward Snell. For my thank-you, I looked through a collection of note cards in the department and chose my favorite, a photograph showing the interior of Morgan Library in the late 19th century. I’ve looked at this photograph many times, but this time – with daguerreotypes on the brain – I noticed something I’d never noticed before. Can you see it?

Look closer:

I knew at once that there was a framed group of daguerreotypes on the wall. Furthermore, it was reasonable to think it was a group of people somehow connected to each other (faculty or students) rather than a bunch of random daguerreotypes framed together (if anyone ever did that anyway). I went to a good scan of the photograph and examined it. The one on the left in the second row caught my eye — I yelped– surely that was Austin Dickinson… I wasn’t looking for him — he just stuck out in some way, perhaps because I’ve seen his big, doughy face a million times already and I have its template impressed on my brain.

My more levelheaded and therefore initially skeptical colleague Chris examined it – and agreed. It then occurred to me that if this daguerreotype showed Austin, was he where he ought to be if the daguerreotypes were in alphabetical order? I counted. He was. The next thing to do was to place the ones with solid identifications in their proper place and then to work down through the list of students. Chris and I had a lot of fun with this part.

In order to do the work, we looked at the daguerreotypes that had some physical aspect that made them stand out – those that showed solarization in the whites that made them glow (like Faunce in the middle of the second row), or that were especially dark; those in which the direction the sitters were facing was a factor; or those that were framed in ovals, which seemed especially visible. These variables allowed us to put the images in place and recreate the framed group that you can see in the library photograph above. So here’s the Class of 1850 in alphabetical order, from left to right, top to bottom. If you want to be a smarty-pants, you could compare them with the identifications in the previous post and see where I was wrong.

In order to do the work, we looked at the daguerreotypes that had some physical aspect that made them stand out – those that showed solarization in the whites that made them glow (like Faunce in the middle of the second row), or that were especially dark; those in which the direction the sitters were facing was a factor; or those that were framed in ovals, which seemed especially visible. These variables allowed us to put the images in place and recreate the framed group that you can see in the library photograph above. So here’s the Class of 1850 in alphabetical order, from left to right, top to bottom. If you want to be a smarty-pants, you could compare them with the identifications in the previous post and see where I was wrong.

Avery, Beebe, Bishop, Cory, Crosby, Dickinson, Ellery, Faunce, Fenn, Garrette, Gay, Gilbert, Gould, Gregory, Hodge, Howland, Manning, Newton, Nickerson, Packard, Sawyer, Shipley, Stimpson, Thompson, Williston (see list of full names at end of post). Daguerreotypist undocumented but most likely J.D. Wells of Northampton.

But – oh no…!

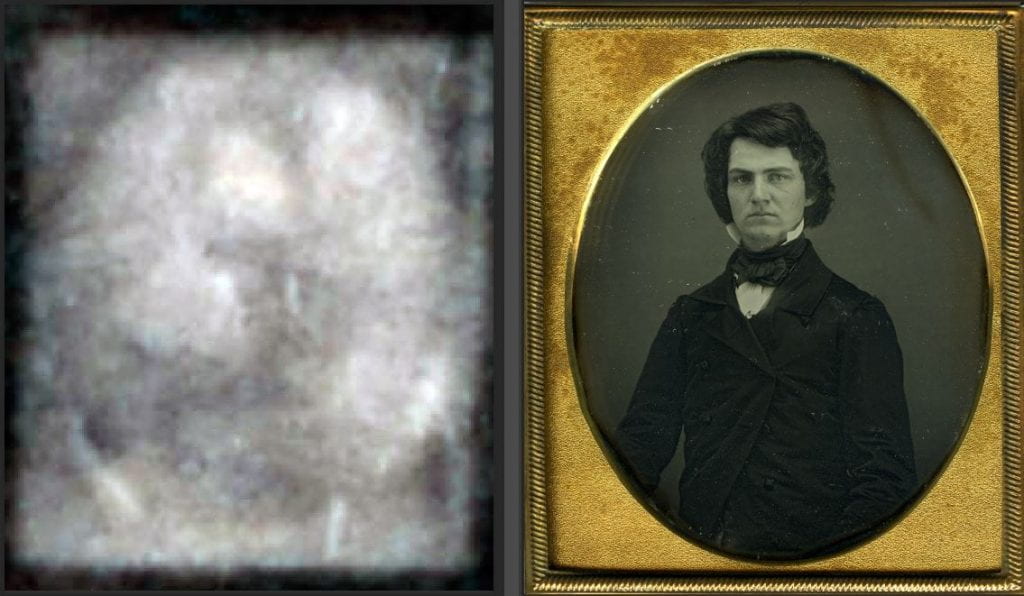

Are you familiar with the expression “sacrifice your darlings”? I remember exactly when I first heard that expression and who said it to me. It’s usually employed (everywhere…tiresomely) as a helpful reminder to edit your writing (good advice, and I attempt to abide by it — I swear), but I also think of it in broader terms to mean giving up something one treasures. In this case, it meant that my heart must be broken and a darling sacrificed, for it revealed that the photograph below — the same photograph that is my computer’s background– is not Henry Shipley, known to his mates as “Ship,” the brilliant bad-boy of his class who couldn’t stay out of trouble and whose tragic story (see second half of earlier post) has become linked in my mind with this particular photograph:

Instead, it’s Minott Sherman Crosby, a schoolteacher and principal of two schools, the Hartford Female Seminary and then Waterbury High School, and later superintendent of schools in Waterbury. He lived to 1897 and had three children with Margaret Maltby Crosby.

This identification continues to disorder my mind and send up a bristling resistance. I still associate that face with Ship, though sadly now. Instead, the real Shipley is — according to the group order — this fellow:

So I put this guy – this Shipley – as the background on a second computer, where he duels across the room with his alter-ego (aka Crosby) for my affection. But I continue to struggle to accept the truth, which is a strange lesson in sacrificing a darling, and in how hard it is to give up a cherished belief in the face of better evidence — a lesson for every era.

So for now, at least, this should be it for the Class of 1850. Unless something else comes up….

***********************************************************************************************

Full list of the graduates of the Class of 1850:

William Fisher Avery (1826-1903)

Albert Graham Beebe (1826-1899)

Henry Walker Bishop (1829-1913)

John Edwin Cory (1825-1865)

Minott Sherman Crosby (1829-1897)

William Austin Dickinson (1829-1895)

John Graeme Ellery (1824-1855)

Daniel Worcester Faunce (1829-1911)

Thomas Legare Fenn (1830-1912)

Edmund Young Garrette (1823-1902)

Augustine Milton Gay (1827-1876)

Archibald Falconer Gilbert (1825-1866)

George Henry Gould (1827-1899)

James John Howard Gregory (1827-1910)

Leicester Porter Hodge (1828-1851)

George Howland (1824-1892)

Jacob Merrill Manning (1824-1882)

Jeremiah Lemuel Newton (1824-1883)

Joseph Nickerson (1828-1882)

David Temple Packard (1824-1880)

Sylvester John Sawyer (1823-1884)

Henry Shipley (1825-1859)

Thomas Morrill Stimpson (1827-1898)

John Howland Thompson (1827-1891)

Lyman Richards Williston (1830-1897)

There were also 15 non-graduates in the class, all of whom departed Amherst long before the daguerreotypes were made.

Brilliant sleuthing done here by AC Archives specialist Mimi Dakin!