It is always thrilling when a single location on campus can pull together from the archival record multiple threads of Amherst’s history. In preparing for Professor Mary Hicks’s Black Studies class in research methods, we discovered the history of the Charles Drew House, a history which incorporated material from five different collections: the Fraternities Collection, the Biographical Files, The Alfred S. Romer Papers, the Building and Grounds Collection, and the Charles Drew House Photo Albums.

The history of the Charles Drew House begins with the Phi Kappa Psi fraternity chapter at Amherst College. Founded in 1895, the fraternity first occupied a home on Amity Street in Amherst. It purchased and remodeled in the late 1910s the mansion owned by Julius Seelye, a former president of the College. The Springfield Union touted the home’s “choicest location” in town and the justification of “as pretentious a motive as the circular porch.”

In the midst of World War II, the fraternity came close to losing its home. Amherst College administration considered prohibiting fraternities on campus. Advocates, including many alumni, convinced the trustees to preserve fraternity life with the condition that certain reforms would be made. In 1946, the trustees of Amherst College announced that fraternities would be required to remove any clause in their constitutions that discriminated against pledges based on race, ethnicity, or religion.

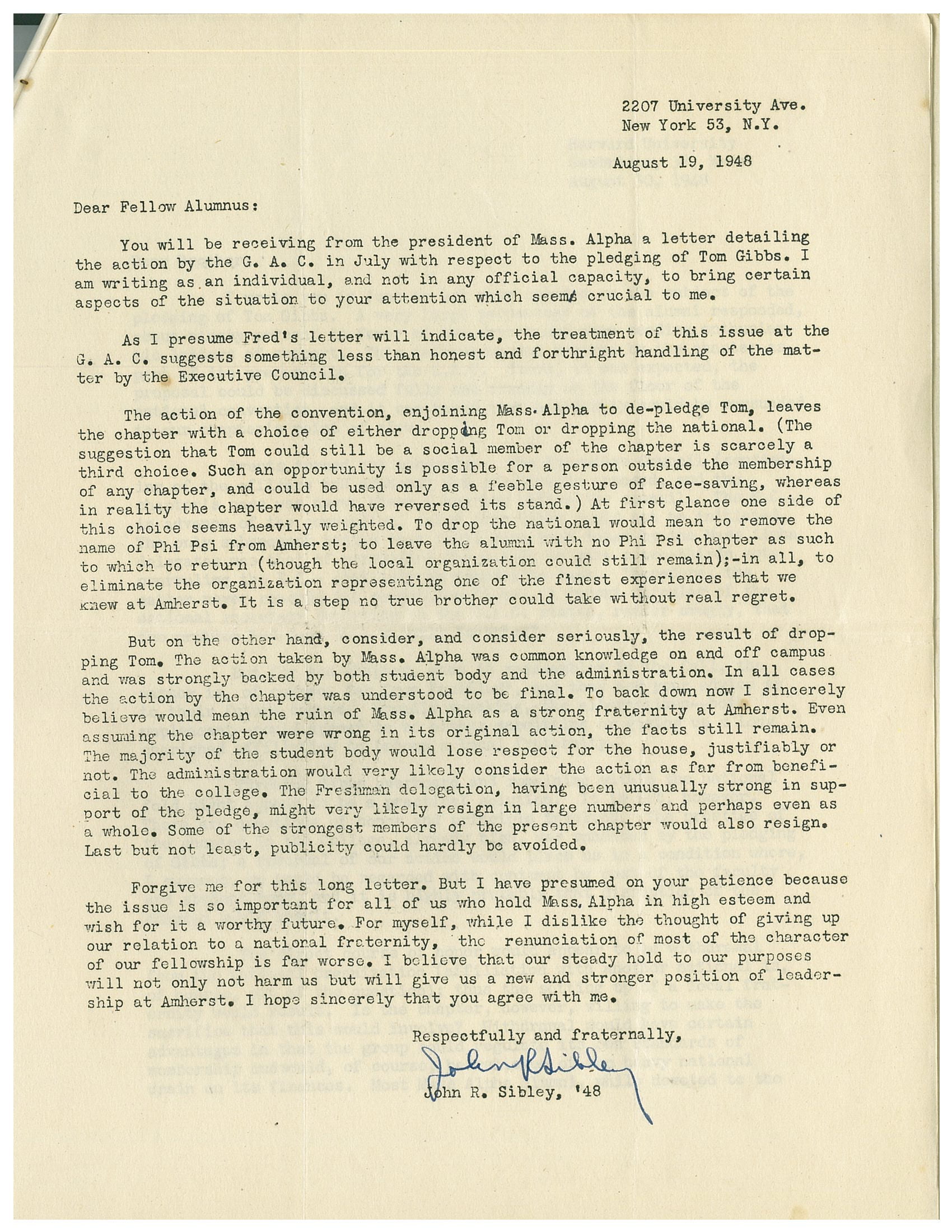

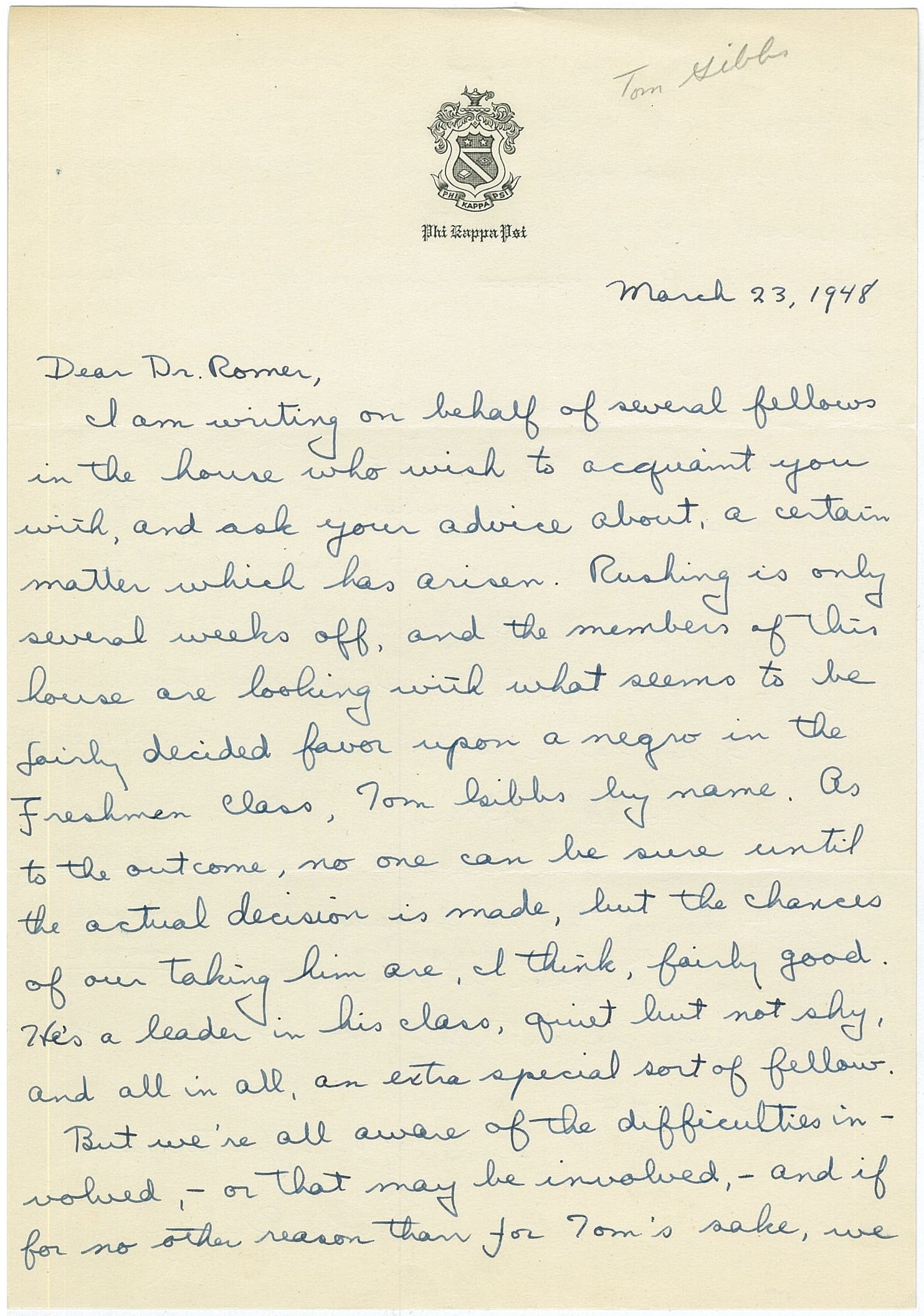

This momentous change challenged the national attitudes toward inclusion in fraternities. This became evident when the Amherst chapter of Phi Kappa Psi pledged Thomas Gibbs, an African American freshman, in the spring of 1948. Gibbs was a member of the track team and a class officer. A fellow Phi Kappa Psi brother described him as “quiet but not shy, and all in all, an extra special sort of fellow.” Students and alumni alike were largely in support of Gibbs joining. The Fraternities Collection in the Amherst College archives provides evidence of community opinion. However, the national organization pressured the Amherst chapter into depledging Gibbs until the fraternity had had ample time to consider the affair. In the fall of 1948, the Amherst chapter polled Amherst alumni and the Phi Kappa Psi national community and moved forward with their plan to pledge Gibbs. The story garnered news interest and the national organization – bristling at Amherst’s perceived public defiance – pulled the Amherst chapter’s charter. The chapter pledged Thomas Gibbs and became a local fraternity: Phi Alpha Psi.

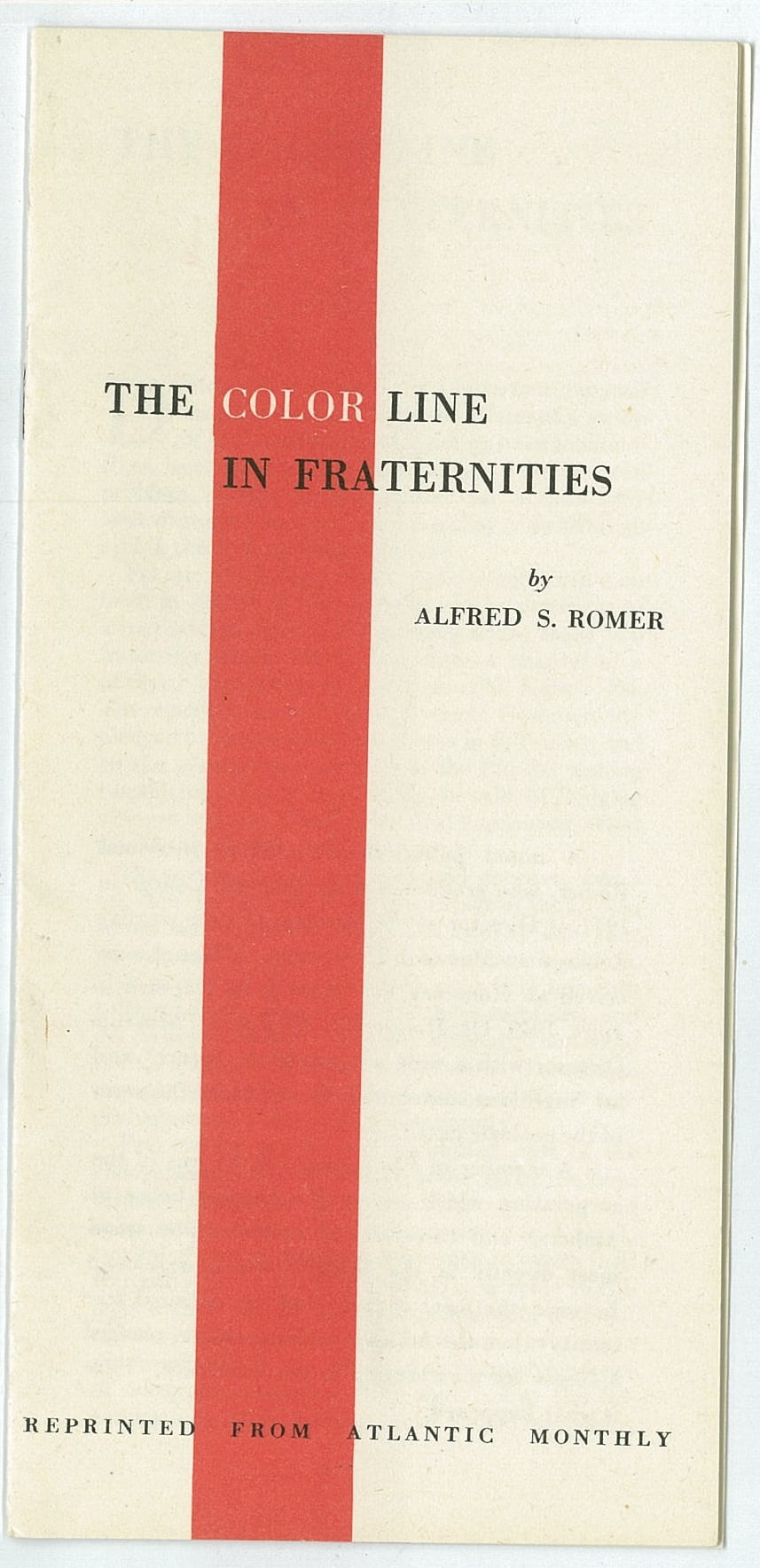

The chair of the Phi Alpha Psi corporation at the time was Alfred Sherwood Romer (AC 1917), the director of Harvard University’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. His papers in the Amherst College archives contain correspondence between Romer, the Phi Kappa Psi brothers, and alumni. The correspondence demonstrates a variety of opinion on the matter. Romer wrote an article, “The Color Line in Fraternities,” which was published in the Atlantic Monthly in 1949. It garnered attention. A student in Illinois read the article in her “Social Problems class” and wrote to Romer in the early 1950s, curious as to the outcome. This prompted Romer to write a postscript to the article.

This exchange between Romer and Miss D. Frederick in 1951 shed further light on the Gibbs/Phi Alpha Psi story. Click on the images to view them in closer detail, and note the secretary’s shorthand on D. Frederick’s letter to Romer.

Charles Drew was born in Washington, D.C., in 1904. He attended Amherst College and graduated in 1926 – afterwards he received an M.D. and a C.M. from McGill University. Charles Drew was known for his pioneering research into blood banks and the use of blood plasma. During the early years of World War II he spearheaded the collection of blood plasma as part of the “Blood for Britain” program. He also was appointed director of the first American Red Cross Blood Bank. He served for many years on the faculty of the Howard University Medical School. Tragically, Drew’s life was cut short in an automobile accident while driving with colleagues to a conference at the Tuskegee Institute. Many organizations honored Charles Drew by putting his name on elementary schools, a medical university, and residence halls at both Howard University and Amherst College.

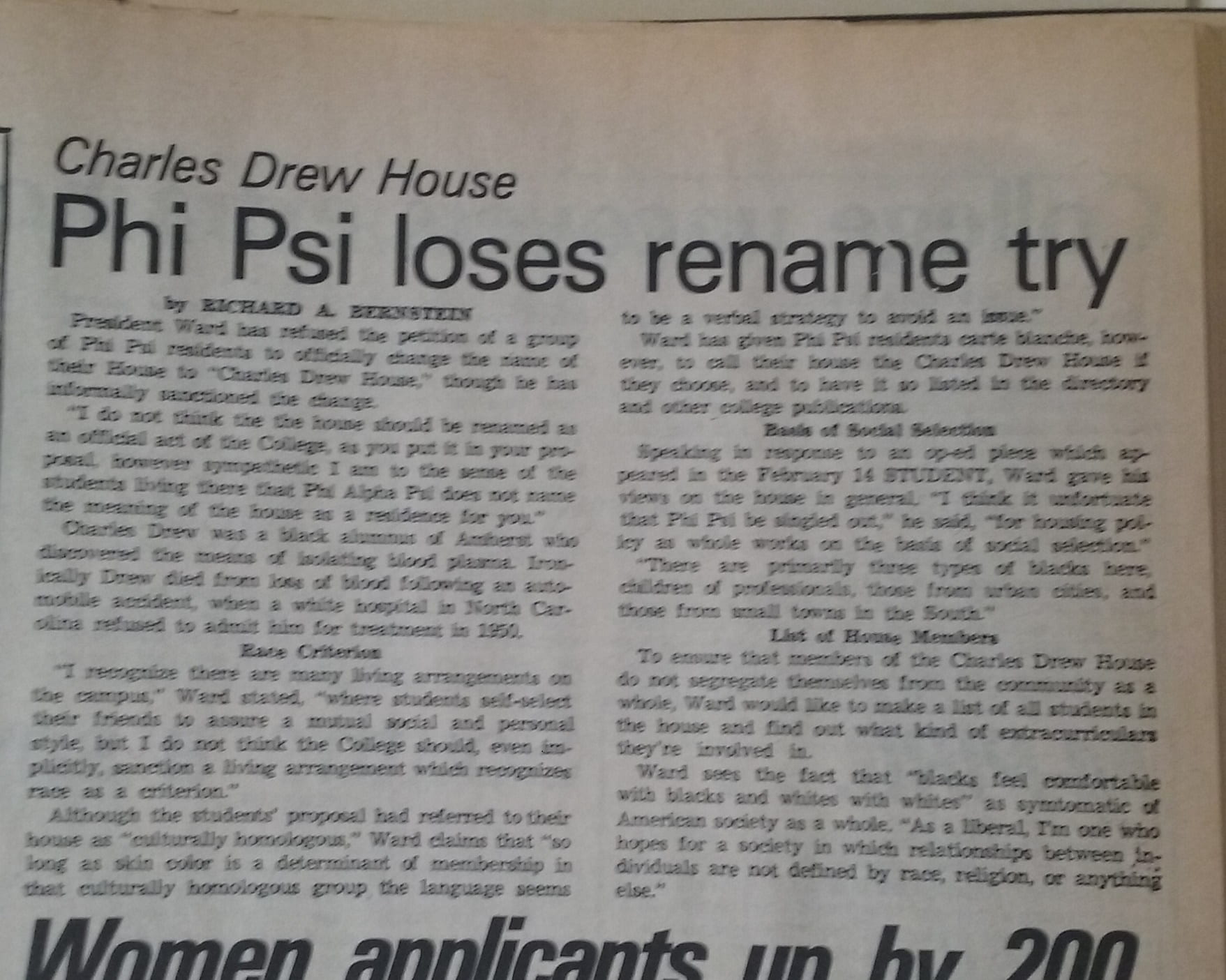

By the mid-1960s, Phi Alpha Psi (also known as Phi Psi) had withdrawn from the fraternity system and were known for their reputation as a counter-cultural institution on campus. In the 1970s Phi Psi pushed for the house to be named after Charles Drew but the organization was denied. For more information on Phi Psi visit Amherst Reacts, a digital humanities project put together by Amherst students in 2016.

In 1984 Amherst College banned fraternities, following the resolutions laid out in the Final Report of the Ad Hoc Committee on Campus Life. The houses were transformed into dormitories and were renamed after significant members of the college community. The unofficial Charles Drew House once again pushed for an official dedication and was granted such in 1987.

Today, the Charles Drew House sponsors “events that will celebrate the achievements of black people such as Charles Drew and explore the cultures of Africa and the Diaspora at large. This house was founded as a space where members of the Amherst community can engage in intellectual debate, social activities, artistic expression, and all other endeavors, which highlight Africa and the Diaspora and the accomplishments of its diverse peoples.” (see the full constitution here)

The Charles Drew House also lives in the Amherst College Archives and Special Collections, where scrapbooks and photograph albums kept by the residents of the Charles Drew House from 1986 to 2010 are held.