One point I often make when talking with students about the books in the Archives & Special Collections is that printing is a capitalist enterprise. What I mean by that is that one must possess sufficient capital to purchase (or hire) a printing press with all of its equipment (e.g. type); then one must pay for the paper and the ink, the labor of setting type, the labor of operating the press, the warehouse space required to store your printed sheets, and so on before any profit can be made. If you want illustrations in your book, that would involve a completely separate process that requires its own specialized equipment and highly skilled labor, all of which requires funds.

It’s especially important to bear in mind the financial underpinnings of print when we look back at the history of scientific publishing. Which gives me an excuse to talk about one of my very favorite books: The Moon: Considered as a Planet, a World, and a Satellite by James Nasmyth (London, 1874).

Here’s a quick summary of Nasmyth’s project from an article by Frances Robertson in the journal Victorian Studies:

Having made his fortune as an industrialist and inventor with his Bridgewater Foundry in Manchester, the mechanical engineer James Nasmyth was able to retire in his late forties, in 1856, in order to devote himself to his longstanding passion for astronomy (Nasmyth, Autobiography 329). His main astronomical project, from 1842, had been a sustained series of lunar observations, culminating in his publication The Moon: Considered as a Planet, a World, and a Satellite (Nasmyth and Carpenter). Among the reasons Nasmyth’s book is noteworthy is that it was one of the first books to be illustrated by photo-mechanical prints.

Nasmyth used his fortune to publish his own peculiar theories about the moon, making full use of the very latest technology to include photographs like these:

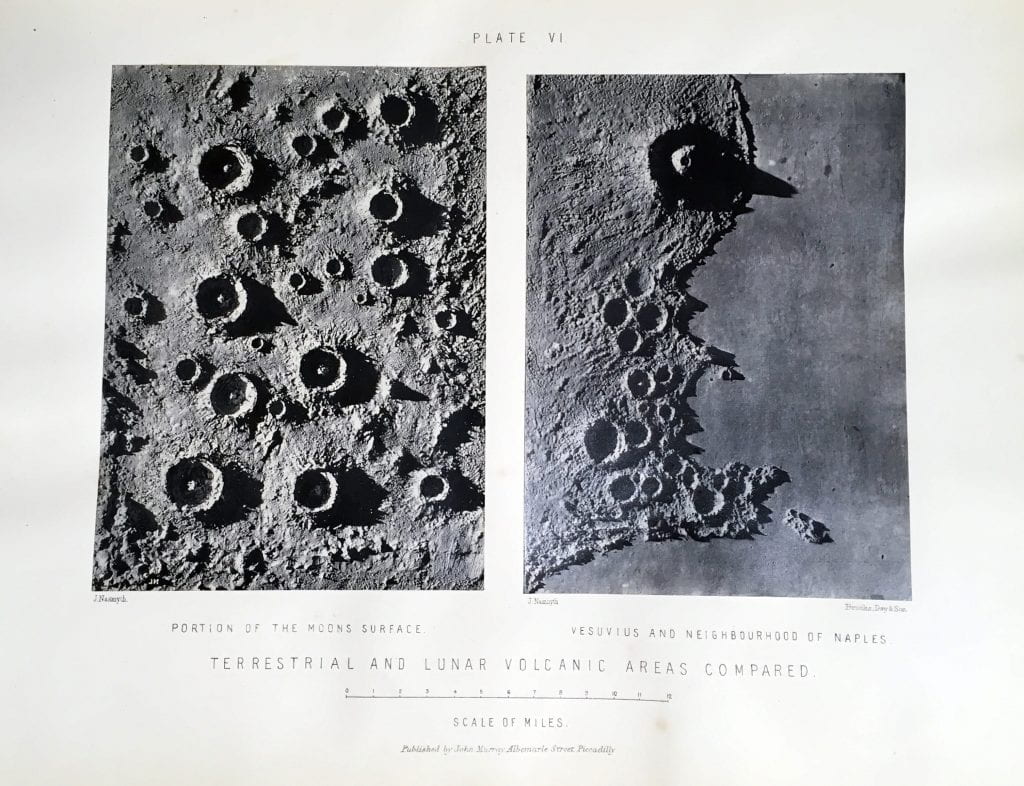

The caption summarizes part of Nasmyth’s theory: when things get old, they shrink and become wrinkled; the moon is old, therefore its mountains may have been formed by shrinkage. He also had theories about volcanic activity being another factor in the formation of the lunar surface, which he supports with another piece of photographic evidence:

Bearing in mind that this work was published in 1874, these couldn’t possibly be actual photographs of the lunar surface and the region around Vesuvius in Italy. Nasmyth had the means to pay for the construction of plaster of Paris models of lunar and terrestrial landscapes, then to pay for photographs of those landscapes, which were then published in his book to support his theories. Of course the lunar surface looks remarkably similar to Vesuvius — he built both of the models!

While these photographs are beautiful to look at, it would be impossible to defend them as reliable scientific evidence of anything.

But if you have sufficient funds to produce a lavishly illustrated book, you can make whatever claims you want. I like to imagine the less wealthy amateur astronomers who read Nasmyth’s book and disagreed, but did not have the same means of promoting their counter-arguments. Nasmyth’s use of a range of illustration techniques makes this work a wonderful specimen for the teaching of book history, but I wouldn’t rely on it for any information about the moon.

All of these points are equally true of another nineteenth-century work in the Archives & Special Collections: Crania Americana; or, A Comparative View of the Skulls of Various Aboriginal Nations of North and South America: to which is Prefixed an Essay on the Varieties of the Human Species by Samuel George Morton (Philadelphia and London, 1839).

Although it was published decades before Nasmyth’s work, these two works are very similar in their use of printing technology to advance a particular scientific theory — a theory that modern science has absolutely disproved. Morton lays out his methods and apparatus for measuring the hundreds of human skulls he had collected.

Many scholars have written about this book, a recent piece that specifically addresses Morton’s use of illustrations appeared in 2014 in the journal American Studies: “”Even the most careless observer”: Race and Visual Discernment in Physical Anthropology from Samuel Morton to Kennewick Man” by Fernando Armstrong-Fumero. Morton’s book boasts of the seventy-eight plates and color map right on the title page, a common practice, but one that ought to remind us that those plates were expensive to produce. The addition of color to the map was also a labor-intensive prospect, since each map was colored by hand:

Many scholars have written about this book, a recent piece that specifically addresses Morton’s use of illustrations appeared in 2014 in the journal American Studies: “”Even the most careless observer”: Race and Visual Discernment in Physical Anthropology from Samuel Morton to Kennewick Man” by Fernando Armstrong-Fumero. Morton’s book boasts of the seventy-eight plates and color map right on the title page, a common practice, but one that ought to remind us that those plates were expensive to produce. The addition of color to the map was also a labor-intensive prospect, since each map was colored by hand:

A map like this one appears to be authoritative, but the data on which it is based are deeply flawed. Morton includes several pages of “Phrenological Measurements” — phrenology being the pseudo-science of determining personality traits and other characteristics by measuring human heads. According to phrenologists, human behaviors such as “Secretiveness,” “Hope,” and other categories can be quantified by measuring the appropriate part of the head:

I am intentionally NOT showing any of the plates of human skulls, mummies, and pickled heads that Morton includes in his work, but here is the “Phrenological Chart” in which the physical areas for each trait are outlined:

Morton was a major contributor to what is now known as “scientific racism” — the claim that different groups of homo sapiens can be categorized and ranked based on “objective” scientific measurements. I will be posting more on this topic in the months ahead as we prepare an exhibition on the topic of the dissemination of scientific racism over the last 300 years and more. The thread that connects the two books in this post runs throughout scientific publishing — the factors of technology and funding have shaped the history of scientific communication almost as much as the data and field work on which these works are based.