What inspires a woman to throw over her life from one day to the next, to go from apparent comfort and a great job in a big city to a remote post in a country she’s never been to, where they speak a language she hasn’t studied at all? And what would possess her to leave the first country after five years of hard work for an entirely different one, retraining herself all over again? How does she go from here:

to here:

–and from being this person (I love the body language here):

What percent of her decision springs from a spirit of adventure, and what percent from “missionary zeal”?

What percent of her decision springs from a spirit of adventure, and what percent from “missionary zeal”?

In the case of Dora Mattoon, it was 110% of each. She couldn’t be contained.

On March 2, 1911, the 27-year-old Dora read an obituary in the New York Times for missionary Maria B. Poole. Maria, who had earlier attended Dora’s church, the Broadway Tabernacle, had died at the mission station in Harpoot, Turkey, of a heart attack after complications from pneumonia. According to Dora’s diary, the story of Maria’s life and work inspired Dora to take her place, almost from one day to the next. She thought quietly over the idea for a few months before announcing her decision in early May. Dr. Charles Jefferson, her pastor at the Broadway Tabernacle, wrote to console her worried parents:

“Your daughter seems to have worked this problem out all by herself. I never once spoke to her on the subject of missions, and was quite surprised when a short time ago she came to me, and told me she was going to apply for the position left vacant by our missionary, Miss Poole. I do not believe that anybody talked to her, or coaxed her into it, or even persuaded her, but that she worked it all out alone in her own heart. And she seems to be quite firm in her decision, feeling convinced in her own mind that she is doing what is right and best. She does not like to go so far from you and her mother, but she feels that you have four other girls… Under the circumstances, then, I do not see what is to be done but to let her carry out her plan. She is a mature woman, in good health, old enough to know her own mind, and to measure her own powers, and however hard it may be for you to have her go so far from you, I believe that in time you will become adjusted to it… She can write to you often, and every seven years she can come home… Having been in Turkey once myself, I do not think of it as far away.” (Letter of May 2, 1911 from Charles Jefferson to Alfred Mattoon.)

By October, Dora was on a ship heading for Turkey to take Maria Poole’s place in Harpoot.

Dora thrived in Turkey. She loved the people – the natives and her colleagues – and she loved the work. Her particular job was to be a touring missionary, to visit small villages in the region and to meet with the “Bible women” there. The Bible women were native Armenians who taught Bible lessons to their fellow citizens for a small salary, and it was Dora’s job to be sure they had what they needed, spiritually and materially. At first she used an interpreter, but over time she learned Armenian and Turkish and was able to conduct meetings herself.

Dora’s work required that she travel from Harpoot across land that was often dangerous from snowstorms, rainstorms, flash floods, and dense fog, not to mention Kurdish tribesmen, who in Dora’s letters seem to alternate between rescues and robbery. Dora traveled by horseback, often for days at a time between one village and the next, and for months at a time over the course of an entire tour. Finding shelter usually meant a stay in a native khan (an extremely rustic inn) where she would share a blanket with fleas on the floor in a smoky, windowless room, separated from other occupants by a blanket curtain. She almost always had a male escort, usually the long-time missionary Henry Riggs, but occasionally she went alone on shorter trips or was accompanied by Mariam Varzoohi, a native teacher in the girls’ college. Dora traveled across hills, jumped off falling horses, waded up to her thighs in snow, got soaked to her skin, and seems to have relished all of it. Whether she’d been a mountaineer before she came to Turkey or whether she realized her love for it in Harpoot, it became a lifelong attachment.

![“The northern way is pleasanter than the southern in that one passes over mountains most of the way, and the khans are better on the whole…I was absent from Harpoot almost five weeks, and two days was the longest time I spent in any one place, so you may know life in one way did not become monotonous. Our principal topic of conversation between here and Sivas was our rascally arabdaji [guides]. This was my first experience of travelling in Turkey without a man, and I find a woman has to do a deal of fighting to get along alone.”](https://consecratedeminence.wordpress.amherst.edu/files/2016/05/turkey-no596.jpg?w=500)

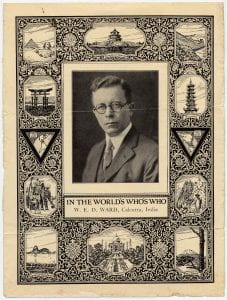

Harpoot’s attractions included Earl Ward, who had been in Turkey since 1909. Dora had met Earl’s twin Mark (both Amherst Class of 1906) before she left for Turkey, so finding Earl at Harpoot would’ve been no surprise. Falling in love with him might’ve been a surprise, though:

“You remember, mother, I used to say men were a nuisance – though I did find them ever so good chums as you know…” (Letter of Oct 17, 1912.)

“Mark [Ward] talked to me more than once about Earl and how much he needed me, though I wouldn’t have it that way at all and came out here with my mind fully made up that whatever happened I simply wouldn’t marry Earl Ward.” (Letter of Oct 17, 1912.)

“…his faults loomed clearer than his virtues for some time!” (Letter of Aug 14, 1913.)

Good chums Dora and Earl worked and played together for the few years they overlapped in Harpoot.

Earl’s tour in Harpoot ended in July of 1913, when he returned to the U.S. and began to work for the YMCA. When Earl left, he and Dora were already engaged and planned to marry when Dora’s tour was up a long two years later.

Dora left Turkey in the spring of 1915, by which time the war had reached Harpoot. That winter, from her home in Massachusetts, she wrote to her sisters, reflecting on what had happened in the brief time since she’d left:

“I wonder where all those dear [Harpoot] friends are now? Many if not most of them killed, I suppose. How dear they all were, and how I loved and admired them! When I came away three of our professors and one of our teachers were in prison, along with eight or ten others of the prominent Armenians, and torture and massacre and deportation had not yet then begun. They came with full force later!” (Letter of Dec 3, 1915.)

In March of 1916, after a brief furlough in the United States, the newlyweds headed for Calcutta, India, on YMCA business. It’s difficult to be certain from only her letters home, but at first Dora seems to have struggled to find her place in India. The climate was hard on her, but in addition she seems to have become an adjunct to Earl’s work in Calcutta rather than having her work equal to his as it had been in Turkey. Her letters suggest that her role was to be primarily a helpmeet to Earl, especially as hostess to people associated with his work, and to do this work so regularly that it was exhausting. Dora needed to be busy, to do her own work, and to feel useful, and while she loved Earl and supported his work, her frustration is apparent in her letters to family.

After a few years and another brief furlough, the Wards were sent to Bombay, and here Dora seems to have gotten back into a role she loved. While Earl devised programs for men and boys, Dora did the same for women and girls. Their duties introduced them to the “chawls” in neighborhoods where their work would take place:

“The chawls are great blocks or tenements of concrete, four storeys high, with twenty rooms on a floor and about five persons to a room probably! We figure there are about 8,000 people in the 22 chawls in that particular area.”

The Wards also traveled around India to inspect other social work sites:

“We had three weeks in Nagpur and spent practically all the time studying the welfare work. I visited the day nursery, or creche, which is being done at the mill, and I also spent some time at an infant welfare center which is being run by the municipality. Then I went to the villages with Irene’s trained nurse and some of her teachers, and Earl spent a lot of evenings, and I some too, visiting the night schools, which is the big approach to people. The welfare work is financed by Empress Mills, who employ 25,000 workers. They live in villages, or bustees, and the welfare work is being done in the bustees. I also looked into the Project Method of teaching…”

Dora was back in business. Click on an image below for gallery.

During vacations the Wards traveled in India as they had in Turkey. Over time Dora became “an old India hand,” familiar with the ways of India – its history, religions, customs, foods, and how to get around. Click for gallery:

After another tour of duty in Calcutta from 1930-32, the world economy forced the YMCA to downsize and the Wards were called home. They were never again posted abroad but remained very active in the U.S. with social work similar to what they had done in Turkey and India.

The Dora Judd Mattoon Ward Papers contain diaries, correspondence, photographs, a nearly full set of the “Harpoot Newsletter” by Ernest Riggs, and other materials about the lives of Dora and Earl Ward. One of its chief strengths is in showing how the lives of missionaries evolved in response to circumstances and changing needs. Dora and Earl started out as “missionaries” in Turkey, but in India they referred to themselves as “social workers” or “welfare workers,” and their work seems distinctly less religious and more specifically related to health, education, and welfare. Where Dora’s work as a touring missionary in Turkey involved a lot of religious teaching, her work in India was more about setting up programs for women and children, and Earl’s was the same for men.

The papers are also important as a record of events in Turkey and India in the first third of the twentieth century. Although the couple seems not to have been especially “political,” their letters contain many comments about the state of affairs first in Turkey during World War I, and later in India during the declining years of the British Raj.

We welcome researchers seeking to use the many Ward collections at Amherst College — those of Edwin St. John Ward (AC 1900), Earl Ward (AC 1906), Mark Hopkins Ward (AC 1906), Dora J.M. Ward, and Paul L. Ward (AC 1933) — or one of the many other missionary collections in our holdings.

Note:

Most of the photographs in this post are by Earl Ward, a few probably by Dora Ward or Fay Emmett Livengood, a fellow missionary in Turkey. Many of Earl’s photographs, including several used in this post, were digitized by his nephew Richard Ward, Class of 1942.

All of the letters in the Dora Judd Mattoon Ward Papers were transcribed by Dora’s faithful niece and our donor, Nancy Kline.