When Millicent Todd Bingham and Richard Sewall wrote their biographies of Emily Dickinson, they each included a section about the influence upon the poet of President Edward Hitchcock and Amherst College. Bingham and Sewall sought to show that one can see in Dickinson’s poems – in her ideas, imagery, and unexpected vocabulary – the effect of Hitchcock and the college he helped establish.

When Millicent Todd Bingham and Richard Sewall wrote their biographies of Emily Dickinson, they each included a section about the influence upon the poet of President Edward Hitchcock and Amherst College. Bingham and Sewall sought to show that one can see in Dickinson’s poems – in her ideas, imagery, and unexpected vocabulary – the effect of Hitchcock and the college he helped establish.

The science cabinets at the College were among Dickinson’s Amherst-related influences. They housed specimens of minerals, shells, fossils, and animals gathered by Hitchcock and his colleagues over the course of their careers and were important campus attractions. Edward Dickinson, the poet’s father, contributed $50 to the Woods cabinet and $100 to Appleton, and his children were no doubt part of the thousands of people who visited them over the decades. There is evidence that Emily attended the opening of the Woods Cabinet (mineralogy, meteorology, geology) in the Octagon in 1848, and she probably also visited the Appleton Cabinet (zoology and ichnology) when it opened in 1855.

The Emily Dickinson International Society meets in Amherst this summer to walk in Dickinson’s town and gather together in the homes she knew, and to absorb as much of her world as possible. They won’t find the same science cabinets that Dickinson knew, but photographs from the collection can recreate something of what she saw.

The photographs below show the campus as it was in middle of the 19th century, as well as some of the exhibitions Dickinson would have seen when she visited the science cabinets and gathered the words and ideas that filled her thoughts and spilled onto paper.

The Woods Cabinet is next to the Octagon in the structure on the left; Appleton Cabinet, a new building at this time, is at far right. Johnson Chapel (middle of long row of buildings) also housed the early elements of the zoological and ichnological cabinets before they were moved to Appleton. Half-plate ambrotype by E. W. Cowles, ca. 1855.

The Woods Cabinet is next to the Octagon in the structure on the left; Appleton Cabinet, a new building at this time, is at far right. Johnson Chapel (middle of long row of buildings) also housed the early elements of the zoological and ichnological cabinets before they were moved to Appleton. Half-plate ambrotype by E. W. Cowles, ca. 1855.

The Visitor’s Guide, published by President Hitchcock’s son Charles in 1862, provides a detailed list of the contents of the “public rooms and cabinets” as they were in 1862 as well as a general history of the collections. It’s still a useful document both for specifics about what was where and for a sense of how people understood and described the contents of the collections.

The Visitor’s Guide, published by President Hitchcock’s son Charles in 1862, provides a detailed list of the contents of the “public rooms and cabinets” as they were in 1862 as well as a general history of the collections. It’s still a useful document both for specifics about what was where and for a sense of how people understood and described the contents of the collections.

The new Appleton Cabinet, housing the Hitchcock Ichnological Cabinet and the Adams Zoological Cabinet. Half-plate ambrotype by E.W. Cowles, ca. 1855. At least one of the rocks outside the entrance appears to have a fossil track in it – see detail below. The man (I’d swear it’s Hitchcock) entering the building carries something under his arm – perhaps more specimens.

The new Appleton Cabinet, housing the Hitchcock Ichnological Cabinet and the Adams Zoological Cabinet. Half-plate ambrotype by E.W. Cowles, ca. 1855. At least one of the rocks outside the entrance appears to have a fossil track in it – see detail below. The man (I’d swear it’s Hitchcock) entering the building carries something under his arm – perhaps more specimens.

The track on the left looks to this amateur like the 14-20” print of “Brontozoum giganteum,” examples of which Appleton apparently had in abundance.

A slightly later (ca. 1865) photograph shows that the rocks in the earlier photograph have been removed, the one with a track probably to the interior of the building and the striated rock perhaps to the area around the “Ninevah Gallery” near the Octagon, which still has an arrangement of boulders near the one moved by the Class of 1857.

A slightly later (ca. 1865) photograph shows that the rocks in the earlier photograph have been removed, the one with a track probably to the interior of the building and the striated rock perhaps to the area around the “Ninevah Gallery” near the Octagon, which still has an arrangement of boulders near the one moved by the Class of 1857.

“[Natural history cabinets] deeply interest and instruct the community surrounding a college, and all who visit it, and thus give reputation to it…almost every one will see enough in nature’s products to awaken interest, inquiry and admiration. This explains the fact that as many as fifteen thousand visitors annually have registered their names in the Amherst Cabinets, small and retired as the place is.” (Edward Hitchcock, “Reminiscences of Amherst College,” p. 112).

“[Natural history cabinets] deeply interest and instruct the community surrounding a college, and all who visit it, and thus give reputation to it…almost every one will see enough in nature’s products to awaken interest, inquiry and admiration. This explains the fact that as many as fifteen thousand visitors annually have registered their names in the Amherst Cabinets, small and retired as the place is.” (Edward Hitchcock, “Reminiscences of Amherst College,” p. 112).

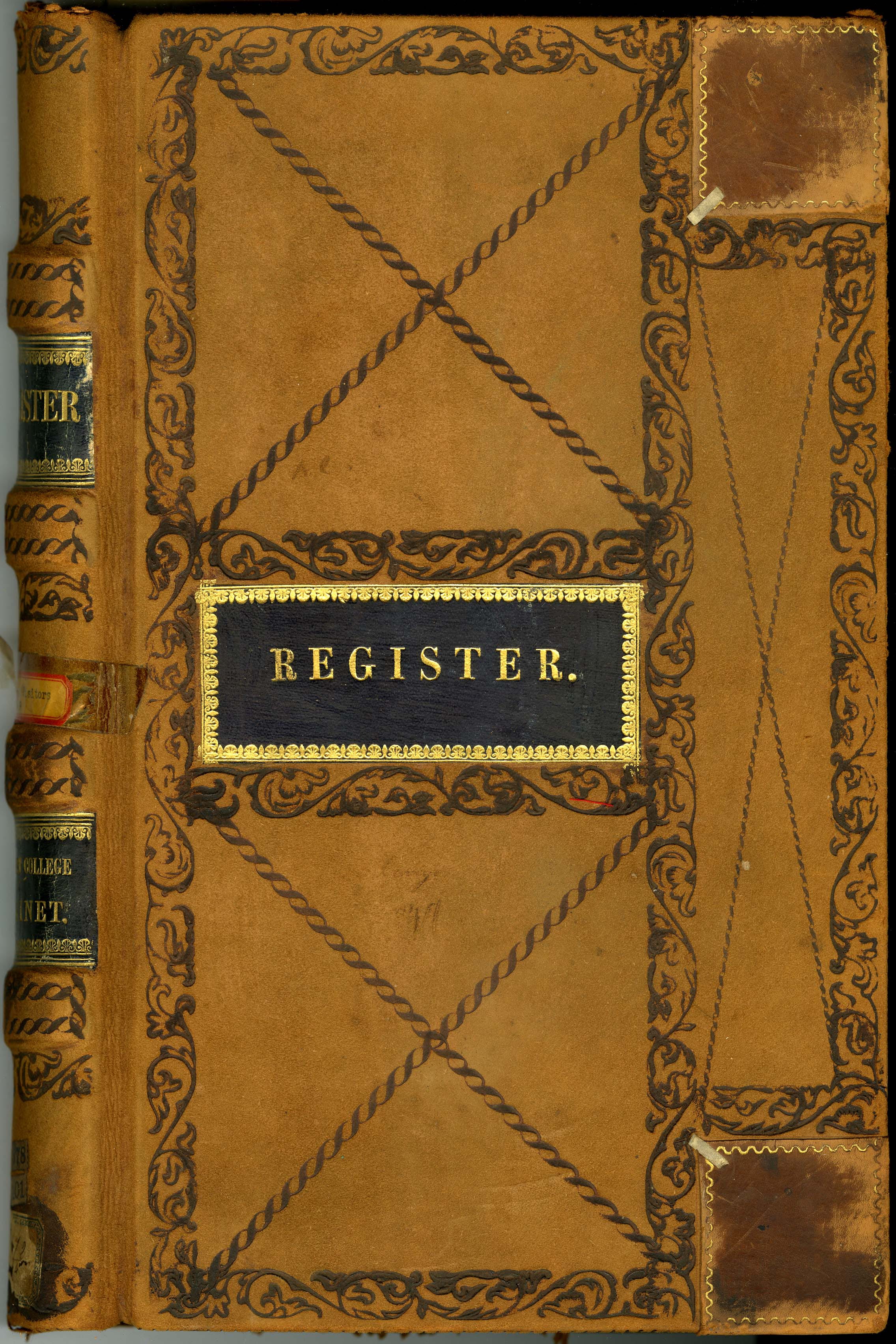

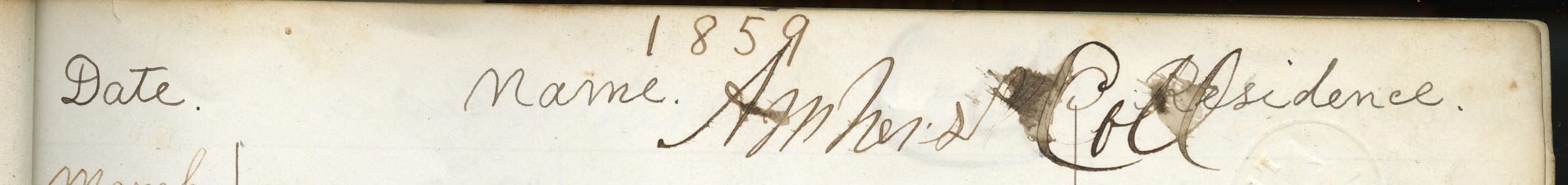

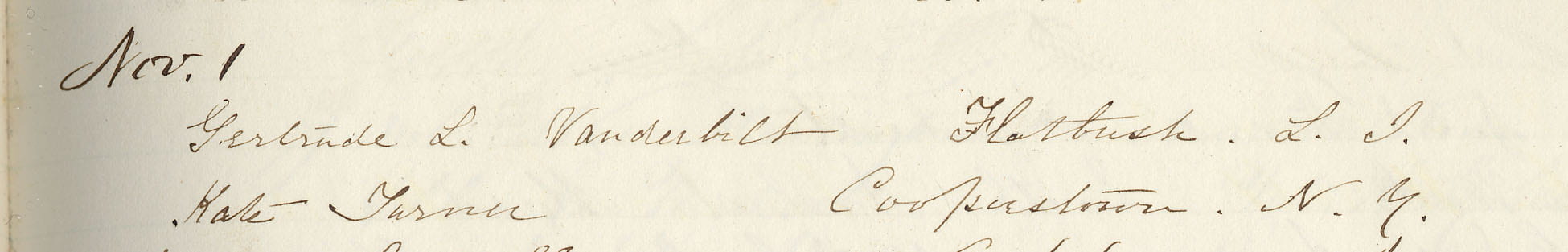

The Appleton Cabinet register commences in March, 1859. So far, Emily Dickinson’s signature has not been located in this large book (Jay Leyda searched it in the 1950s), but there are many other interesting signatures.

The Appleton Cabinet register commences in March, 1859. So far, Emily Dickinson’s signature has not been located in this large book (Jay Leyda searched it in the 1950s), but there are many other interesting signatures. Among the famous people who visited Appleton are Nicholas Nickleby, Smike, and members of the Squeers family. It is not clear whether Oliver Twist was part of their group or visited on his own.

Among the famous people who visited Appleton are Nicholas Nickleby, Smike, and members of the Squeers family. It is not clear whether Oliver Twist was part of their group or visited on his own.

![]() Joseph Smith and 12 ladies (Smith, who had been shot dead in 1844, evidently returned from the celestial kingdom to visit Appleton)

Joseph Smith and 12 ladies (Smith, who had been shot dead in 1844, evidently returned from the celestial kingdom to visit Appleton)

Dickinson’s friend Kate Turner and Kate’s friend Gertrude Vanderbilt visited Sue Dickinson in the fall of 1861. There is no record of whether they also saw the poet, who was experiencing a personal crisis at this time – her “terror since September,” as she described it the following spring.

Dickinson’s friend Kate Turner and Kate’s friend Gertrude Vanderbilt visited Sue Dickinson in the fall of 1861. There is no record of whether they also saw the poet, who was experiencing a personal crisis at this time – her “terror since September,” as she described it the following spring.

The Ichnological Cabinet in Appleton was Edward’s Hitchcock’s great joy. He described the history of his collection in his “Reminiscences” and his son described it in the Visitor’s Guide above: “Great care has been taken by the position of the tables, sometimes horizontal and sometimes inclined, and especially by the position of the large slabs on their edges, to make the light fall on them most advantageously….The main principle of the arrangement was to place the specimens so that the light should fall obliquely upon their faces.” (Guide, p. 57) Visible in this photograph: “Near the middle of the room there is suspended from the ceiling the leg of the great Moa, or dinornis, lately discovered in the alluvium of new Zealand, where it may have lived within a few hundred years. The two upper bones, the femur and the tibia, are wooden models of bones in other cabinets. But the lower piece, the tarso-metatarsal and the foot, excepting three of the phalanges, are true bone, from New Zealand. Not far distant hangs the model of an egg of a still larger bird, the Aepyornis, from Madagascar; the original of which is in Paris.” (p. 67)

The Ichnological Cabinet in Appleton was Edward’s Hitchcock’s great joy. He described the history of his collection in his “Reminiscences” and his son described it in the Visitor’s Guide above: “Great care has been taken by the position of the tables, sometimes horizontal and sometimes inclined, and especially by the position of the large slabs on their edges, to make the light fall on them most advantageously….The main principle of the arrangement was to place the specimens so that the light should fall obliquely upon their faces.” (Guide, p. 57) Visible in this photograph: “Near the middle of the room there is suspended from the ceiling the leg of the great Moa, or dinornis, lately discovered in the alluvium of new Zealand, where it may have lived within a few hundred years. The two upper bones, the femur and the tibia, are wooden models of bones in other cabinets. But the lower piece, the tarso-metatarsal and the foot, excepting three of the phalanges, are true bone, from New Zealand. Not far distant hangs the model of an egg of a still larger bird, the Aepyornis, from Madagascar; the original of which is in Paris.” (p. 67)

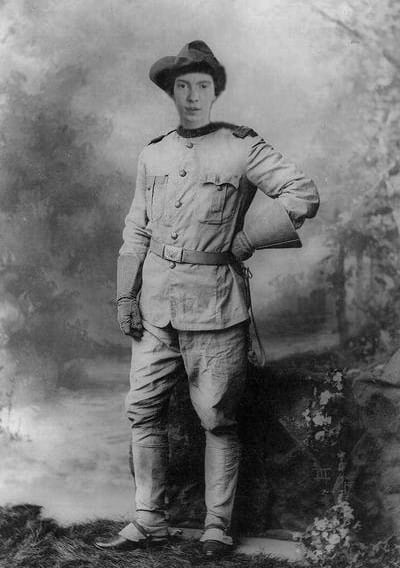

The photograph above shows Charles Baker Adams, Class of 1834, and a man obsessed with science, especially conchology and entomology. Adams gave the bulk of the specimens for the Zoological Collection while it was located in the Chapel and then the Woods Cabinet but didn’t live to see it gathered in Appleton. In 1852 despite ill health, he insisted on a return expedition to the tropics and could not be dissuaded, even by the discouragement of the trustees of the College. “He went, and stopping at the hospitable residence of a friend in St. Thomas, was advised to keep within doors till the yellow fever had subsided. But his love of science set at nought the suggestions of prudence, with the remark that there was no fever among the shell fish, and a little exposure brought on the fever of which he died.” (Reminiscences, p. 96-7)

The photograph above shows Charles Baker Adams, Class of 1834, and a man obsessed with science, especially conchology and entomology. Adams gave the bulk of the specimens for the Zoological Collection while it was located in the Chapel and then the Woods Cabinet but didn’t live to see it gathered in Appleton. In 1852 despite ill health, he insisted on a return expedition to the tropics and could not be dissuaded, even by the discouragement of the trustees of the College. “He went, and stopping at the hospitable residence of a friend in St. Thomas, was advised to keep within doors till the yellow fever had subsided. But his love of science set at nought the suggestions of prudence, with the remark that there was no fever among the shell fish, and a little exposure brought on the fever of which he died.” (Reminiscences, p. 96-7)

At the opening of the Woods Cabinet in 1848, Adams said: “The efforts of naturalists to exhibit the true order of nature, can never fail to gratify a correct and refined taste. Such order is of far higher origin than mere human invention, and is so perfect as to harmonize no less with our emotions of beauty than with our ideas of fitness and method. It is indeed one of the most delightful features of science, that the farther she advances in a correct knowledge of nature, the more systematically and harmoniously are all the powers of the intellect and the emotions of beauty and virtue gratified and invigorated. Nor can the lesson of humility be lost on the lover of science, since his highest efforts consist only in the discovery and exhibition of a beauty and perfection, which not only does not originate in him, but which extends far beyond the most distant flights of his imagination.” (Guide, p. 111) Imagine the effect of these ideas on Dickinson, who is thought to have been at the ceremony.

After Adams’s death, another well known Amherst man, William S. Clark, took over the zoological collection and was responsible for many of the specimens of large mammals seen in the pictures below.

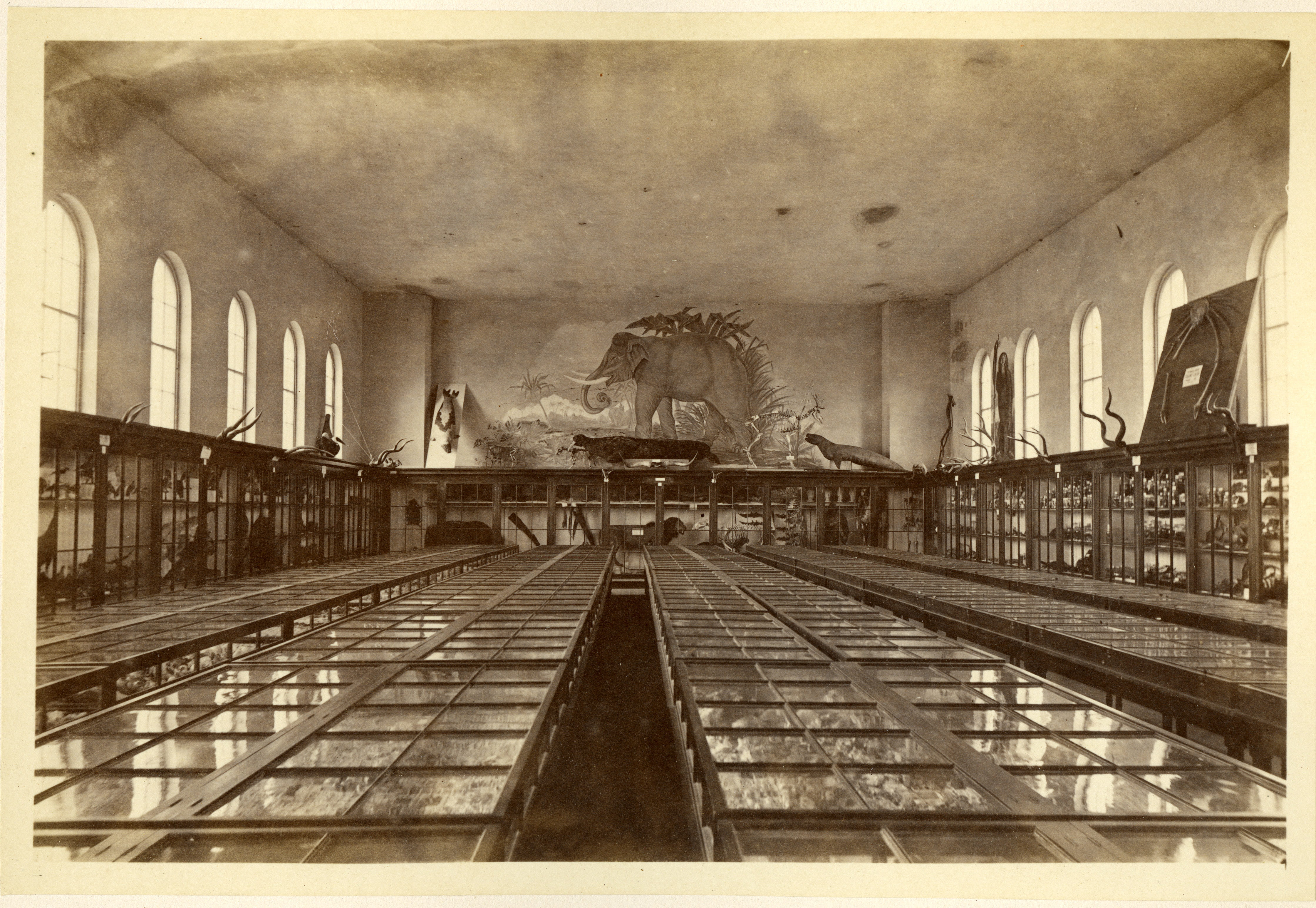

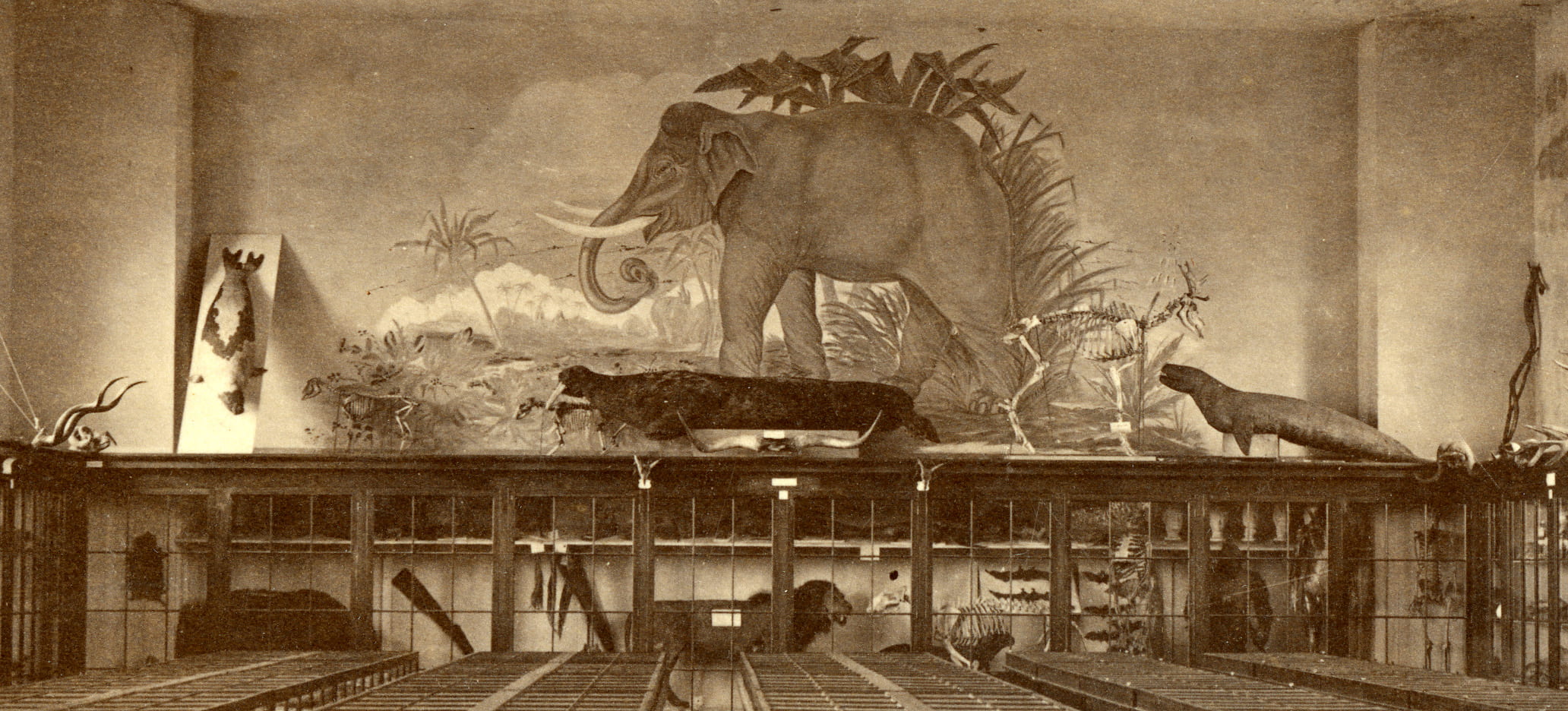

The Adams Zoological Cabinet in Appleton: “The first thing that attracts the attention of the visitor is the paintings upon the walls. Upon the west end of the room is represented an elephant, in the mist of tropical scenery; It appears to best advantage when viewed from the east end of the room…” (Guide, p. 86)

The Adams Zoological Cabinet in Appleton: “The first thing that attracts the attention of the visitor is the paintings upon the walls. Upon the west end of the room is represented an elephant, in the mist of tropical scenery; It appears to best advantage when viewed from the east end of the room…” (Guide, p. 86)

Regarding the mammals case, “Upon the third shelf the variety is greater. Here may be seen the skulls of many small animals; the teeth of many more, such as the whale, camel, elephant, and hippopotamus; the tail of an elephant, the skin of a rhinoceros; feet of a bear; skulls of monkeys; daguerreotype of the Aztec children, etc. Upon the upper shelves of this and the next case will be seen models of the heads of men distinguished for good or bad qualities, by the side of the heads of various wild and domesticated animals. These specimens were designed to illustrate phrenology…. Commencing at the right-hand side of the long case at the west end of the room, one sees first some monstrosities. One is a very fine specimen of a double calf…. Another is a double-headed lamb, and the third is a calf possessing a rudimentary porcine snout. Next is a fine panther, called also American cougar, catamount, and Indian devil. It is one of the cat tribe.” (Guide, p 93-4)

Regarding the mammals case, “Upon the third shelf the variety is greater. Here may be seen the skulls of many small animals; the teeth of many more, such as the whale, camel, elephant, and hippopotamus; the tail of an elephant, the skin of a rhinoceros; feet of a bear; skulls of monkeys; daguerreotype of the Aztec children, etc. Upon the upper shelves of this and the next case will be seen models of the heads of men distinguished for good or bad qualities, by the side of the heads of various wild and domesticated animals. These specimens were designed to illustrate phrenology…. Commencing at the right-hand side of the long case at the west end of the room, one sees first some monstrosities. One is a very fine specimen of a double calf…. Another is a double-headed lamb, and the third is a calf possessing a rudimentary porcine snout. Next is a fine panther, called also American cougar, catamount, and Indian devil. It is one of the cat tribe.” (Guide, p 93-4)

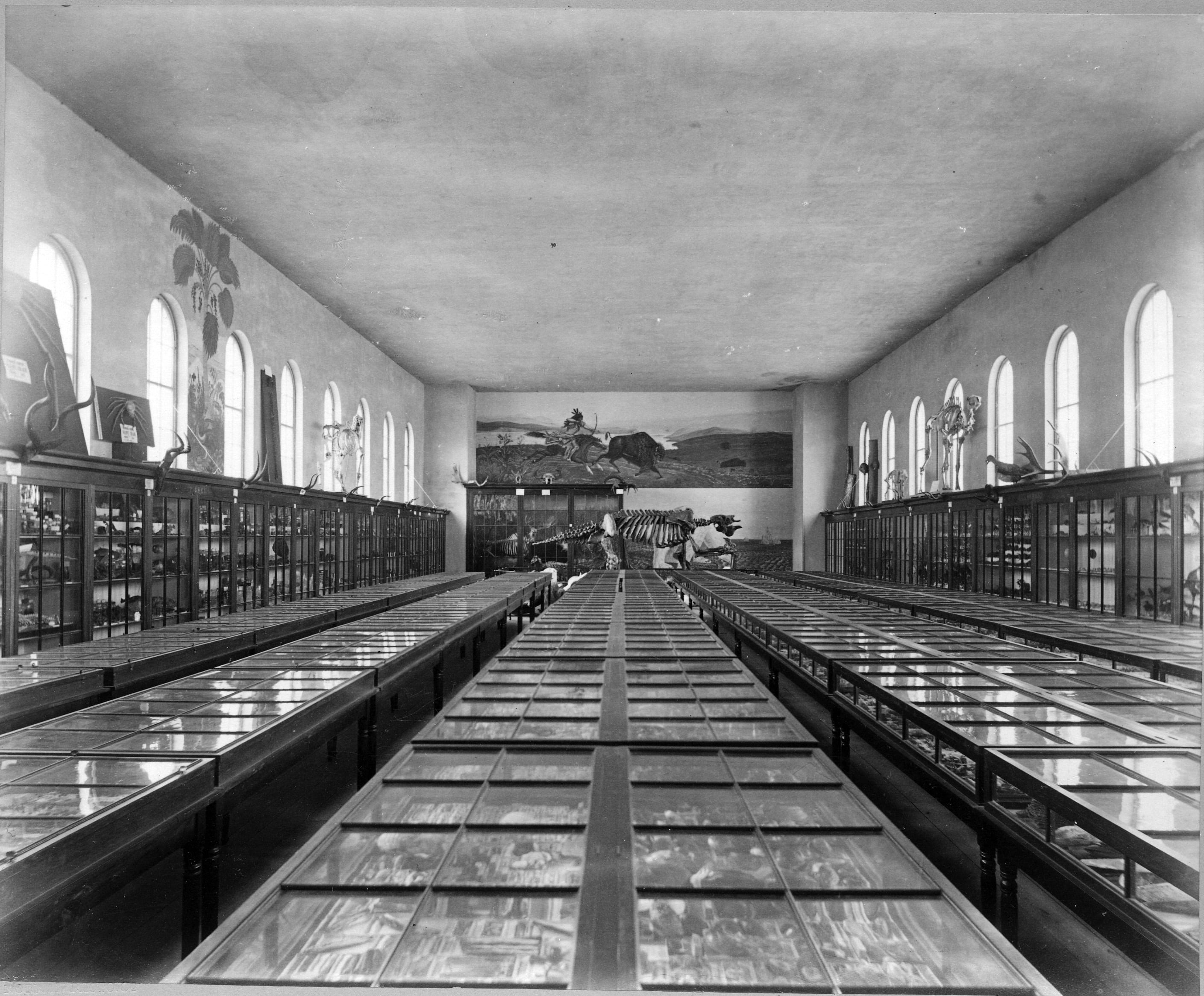

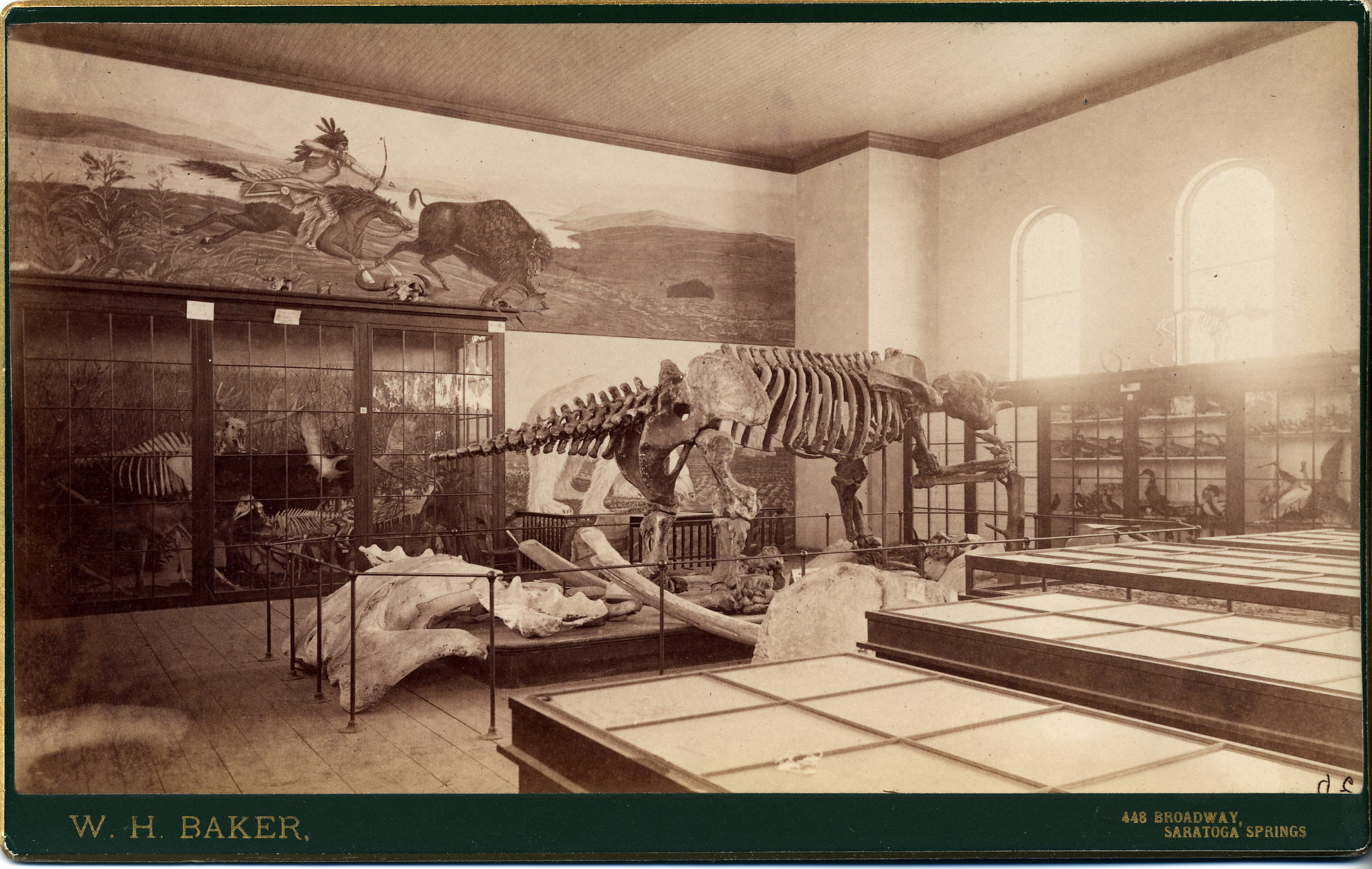

Looking east, “so, too, the representations of Arctic scenery, and of a western buffalo hunt, over the stairs, appear best from the west end of the room…” (Guide, 86)

Looking east, “so, too, the representations of Arctic scenery, and of a western buffalo hunt, over the stairs, appear best from the west end of the room…” (Guide, 86)

“Inside the large glazed case, near the stairs, is a representation of the scenery of a Northern winter, in which a moose is located. When this painting was executed, only a solitary moose occupied the case; but now, since the accumulation of specimens, the scene is not so appropriate.” (Guide, 87)

“Inside the large glazed case, near the stairs, is a representation of the scenery of a Northern winter, in which a moose is located. When this painting was executed, only a solitary moose occupied the case; but now, since the accumulation of specimens, the scene is not so appropriate.” (Guide, 87)

“Upon the north side of the room are represented a South American anaconda attempting to ‘charm’ a parrot, and the huge African ape, the gorilla, the nearest approach of the animal kingdom to man.” (Guide, 86-7)

“Upon the north side of the room are represented a South American anaconda attempting to ‘charm’ a parrot, and the huge African ape, the gorilla, the nearest approach of the animal kingdom to man.” (Guide, 86-7)

“Several important specimens have recently been received for the Zoological Museum…. Among them are the stuffed skin and skeleton of the African Gorilla, presented by Rev. Wm. Walker, of Gaboon, West Africa. No other cabinet in the country, at this date, is so largely represented by specimens of this animal. It being the nearest approach of the animals to man, these specimens have attracted great interest, particularly as they so clearly show the falsity of the notion that the gorilla could ever have changed into man by the ‘law of selection.’ The skin was stuffed by Jillson of Fentonville, and the skeleton mounted by my oldest son.” (Reminscences, p. 95)

“Several important specimens have recently been received for the Zoological Museum…. Among them are the stuffed skin and skeleton of the African Gorilla, presented by Rev. Wm. Walker, of Gaboon, West Africa. No other cabinet in the country, at this date, is so largely represented by specimens of this animal. It being the nearest approach of the animals to man, these specimens have attracted great interest, particularly as they so clearly show the falsity of the notion that the gorilla could ever have changed into man by the ‘law of selection.’ The skin was stuffed by Jillson of Fentonville, and the skeleton mounted by my oldest son.” (Reminscences, p. 95)

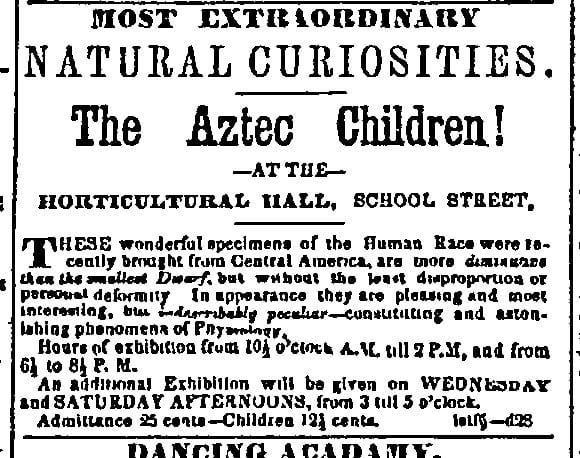

When I envisioned this post, I thought I would write about one item in particular, our daguerreotype of the “Aztec children” who toured with P.T. Barnum in the 1850s. However, Maximo and Bartola, the microcephalic children from El Salvador, received full treatment in a nice blog post from a few months ago. I like to consider that Dickinson probably saw this daguerreotype in Appleton (west end!), even though you would seek in vain for “Aztec children” or “microcephalic” in her poetry or letters.

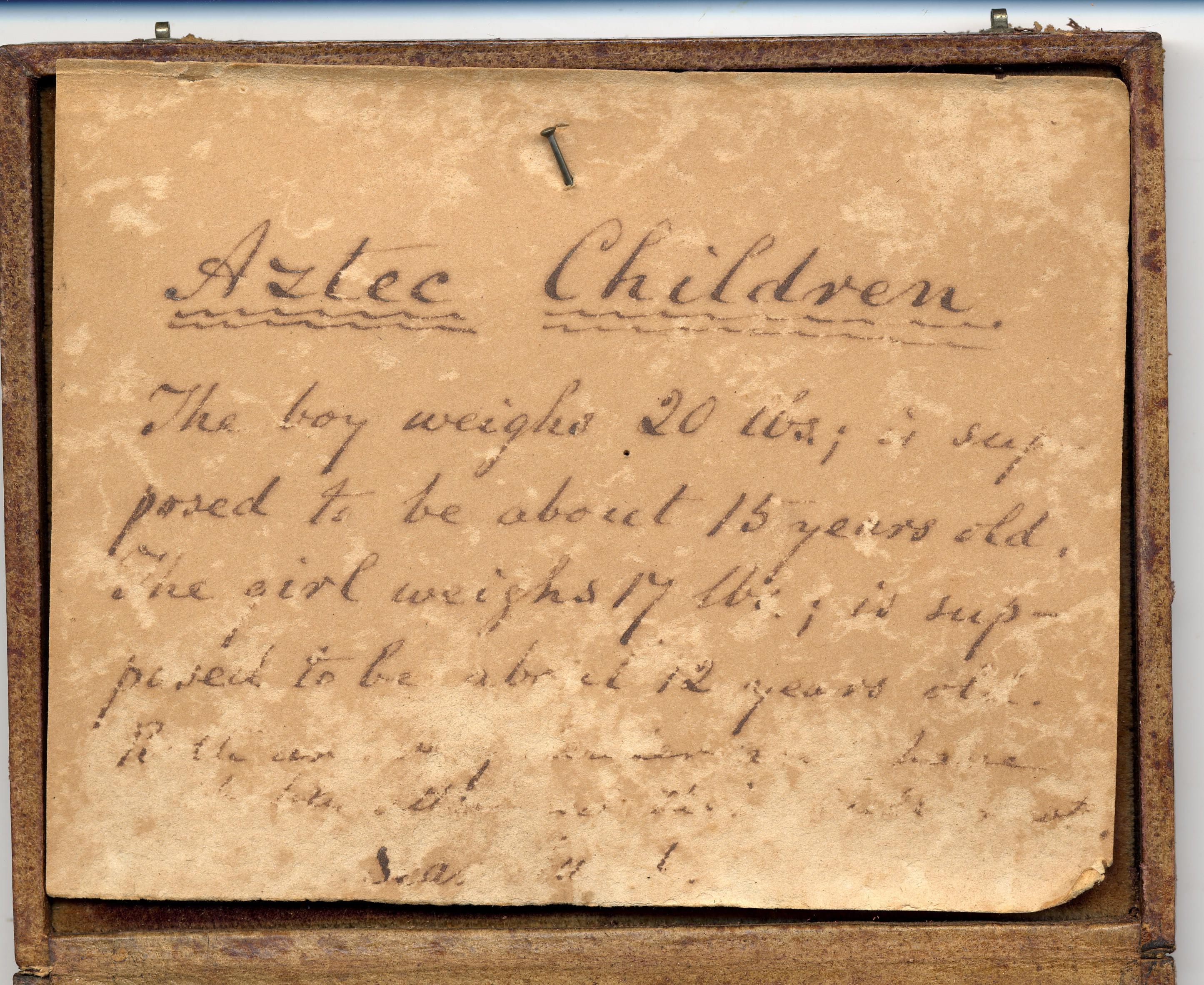

Our daguerreotype was most likely a purchase by Professor Adams during the visit to Boston by Barnum’s circus in late 1850-51. The daguerreotype, perhaps one of many sold during the tour, was taken by Beckers & Piard of New York, ca. 1850. The half-legible inscription (in Adams’s hand?) pinned to the velvet liner says: “Aztec Children. The boy weighs 20 lbs; is supposed to be about 15 years old. The girl weighs 17 lbs; is supposed to be about 12 years old.” The rest is frustratingly illegible, even in Photoshop.

Our daguerreotype was most likely a purchase by Professor Adams during the visit to Boston by Barnum’s circus in late 1850-51. The daguerreotype, perhaps one of many sold during the tour, was taken by Beckers & Piard of New York, ca. 1850. The half-legible inscription (in Adams’s hand?) pinned to the velvet liner says: “Aztec Children. The boy weighs 20 lbs; is supposed to be about 15 years old. The girl weighs 17 lbs; is supposed to be about 12 years old.” The rest is frustratingly illegible, even in Photoshop.

Hitchcock said of natural history collections in colleges devoted to a liberal education, “they are indispensable to give students a knowledge of the natural productions of different parts of the earth, and without which, their views would be narrow, and they would be liable to constant blunders in their literary productions” (Reminiscences, 111). Visitors today should attend the cabinet called the Beneski Museum, a facility and collection that would make Hitchcock and his colleagues proud and provide inspiration for poets of all stripes.

Very interesting and well researched!