A recent acquisition that we purchased at auction was a folder of letters written to Sheridan Gibney (AC 1925). Gibney was a very successful playwright, Oscar-winning Hollywood screenwriter, and three-time president of the Screenwriter’s Guild. He wrote dozens of successful screenplays, two of which, in particular, became film classics: I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932) and The Story of Louis Pasteur (1936), both starring Paul Muni. For the Pasteur biopic, Gibney won two Oscars for Best Writing.

The newly acquired letters will make a good addition to our existing collection of Gibney’s papers.

Gibney’s third and final tenure as president of the Screenwriter’s Guild coincided with the infamous anti-Communist “witch hunt” by the House Un-American Activities Committee beginning in 1947. For that reason, his career is a representative case for the fraught relationship between culture and politics. As he wrote in his brief unpublished memoir (available in his biographical file in the Archives), Gibney always considered himself to be against Communism, but his position as guild president brought his career to a halt when the so-called “unfriendly witnesses” at the House committee hearings implicated the Screenwriter’s Guild as a hotbed of Communism — and Gibney was guilty by association.

His success in drama notwithstanding, Gibney’s great love, especially during his undergraduate years at Amherst, was poetry. Robert Frost considered him one of his best pupils. At one critical point in his undergraduate career, Gibney felt alienated by what he perceived as a lack of intellectual seriousness at Amherst. He considered dropping out to write and travel in Europe, citing Frost as his model: he, Frost, never earned a college degree yet supported himself by writing, teaching and lecturing — even, for a time, farming.

Gibney ultimately went on to complete his Amherst degree (and even earned an honorary degree from the college in 1938). His youthful desire to get away to Europe to have new experiences and write was fulfilled after graduation, when he sailed to France. His papers here contain dozens of interesting letters to his mother, as well as to his mentor, the writer, professor of English, and composer John Erskine. His letters from Paris in 1925 — the Paris of expatriate writers such as Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemingway, Ezra Pound and James Joyce — are full of rather earnest but pleasure-filled observations, and flashes of writerly enthusiasm. Gibney was a man ready to make his mark on the world.

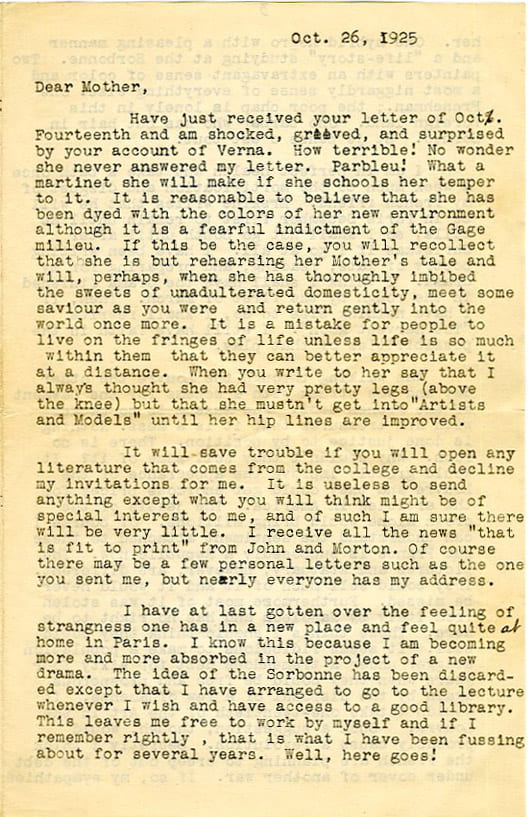

Among his many letters home, this one, dated October 26, 1925 (and below it, an excerpt) gives a flavor of his experience at the time:

An excerpt:

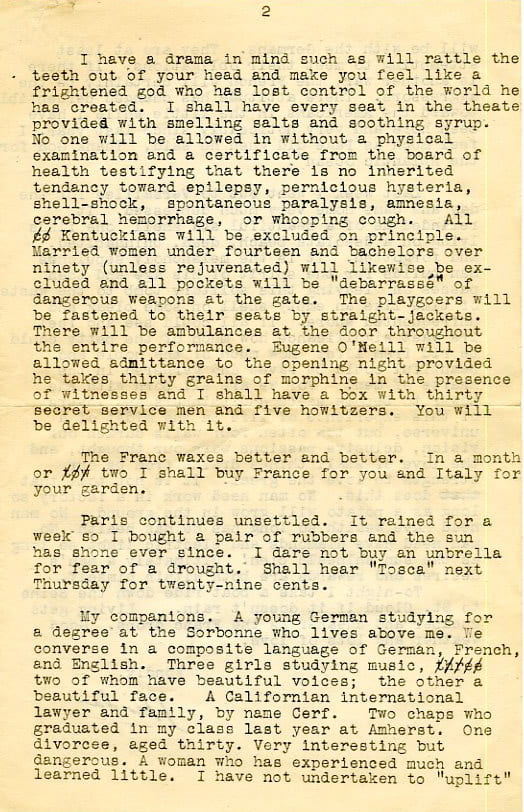

I have a drama in mind such as will rattle the teeth out of your head and make you feel like a frightened god who has lost control of the world he has created. I shall have every seat in the theatre provided with smelling salts and soothing syrup. No one will be allowed in without a physical examination and a certificate from the board of health testifying that there is no inherited tendency toward epilepsy, pernicious hysteria, shell-shock, spontaneous paralysis, amnesia, cerebral hemorrhage, or whooping cough. All Kentuckians will be excluded on principle. Married women under fourteen and bachelors over ninety (unless rejuvenated) will likewise be excluded and all pockets will be “débarrassé” of dangerous weapons at the gate. The playgoers will be fastened to their seats by straight-jackets. There will be ambulances at the door throughout the entire performance. Eugene O’Neill will be allowed admittance to the opening night provided he takes thirty grains of morphine in the presence of witnesses and I shall have a box with thirty secret service men and five howitzers. You will be delighted with it.

The franc waxes better and better. In a month or two I shall buy France for you and Italy for your garden.

Paris continues unsettled. It rained for a week so I bought a pair of rubbers and the sun has shone ever since. I dare not buy an umbrella for fear of drought. Shall hear Tosca next Thursday for twenty-nine cents.

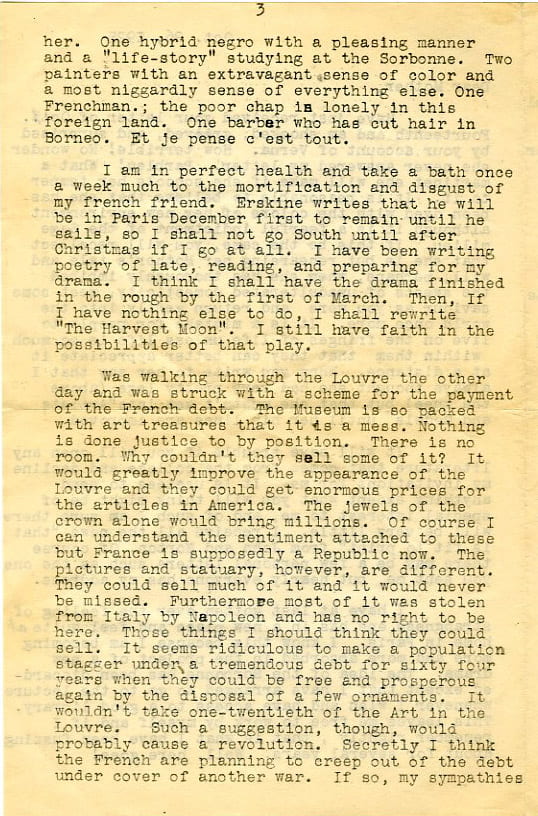

My companions. A young German studying for a degree at the Sorbonne lives above me. We converse in a composite language of German, French, and English. Three girls studying music, two of whom have beautiful voices: the other a beautiful face. A Californian international lawyer and family, by name Cerf. Two chaps who graduated in my class last year at Amherst. One divorcee, aged thirty. Very interesting but dangerous. A woman who has experienced much and learned little. I have not undertaken to “uplift” her. One hybrid negro with a pleasing manner and a “life story” studying at the Sorbonne. Two painters with an extravagant sense of color and a most niggardly sense of everything else. One Frenchman; the poor chap is lonely in this foreign land. One barber who has cut hair in Borneo. Et je pense c’est tout.

Erskine writes that he will be in Paris December first to remain until he sails, so I shall not go South until after Christmas if I go at all. I have been writing poetry of late, reading, and preparing for my drama. I think I shall have the drama finished in the rough by the first of March. Then, if I have nothing else to do, I shall rewrite The Harvest Moon. I still have faith in the possibilities of that play.

[…]

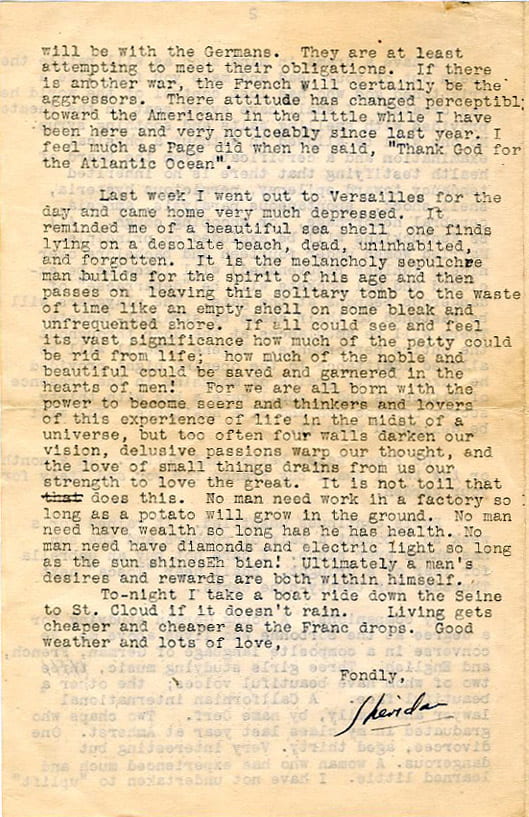

Last week I went out to Versailles for the day and came home very much depressed. It reminded me of a beautiful sea shell one finds on a desolate beach, dead, uninhabited, and forgotten. It is the melancholy sepulchre man builds for the spirit of his age and then passes on leaving this solitary tomb to the waste of time like an empty shell on some bleak and unfrequented shore. If all could see and feel its vast significance how much of the petty could be rid from life; how much of the noble and beautiful could be saved and garnered in the hearts of men! For we are all born with the power to become seers and thinkers and lovers of this experience of life in the midst of a universe, but too often four walls darken our vision, delusive passions warm our thought, and the love of small things drains from us our strength to love the great. It is not toil that does this. No man need work in a factory so long as a potato will grow in the ground. No man need have wealth so long as he has health. No man need have diamonds and electric light so long as the sun shines. Eh bien! Ultimately a man’s desires and rewards are both within himself.

Tonight I take a boat ride down the Seine to St. Cloud if it doesn’t rain. Living gets cheaper and cheaper as the franc drops again. Good weather and lots of love.

Fondly,

Sheridan