The topic of tax-exempt status has been much in the news lately—who gets it, what they do with it, and what IRS hoops they have to jump through in order to secure it. In spring 2013, news outlets revealed that the IRS had singled out some conservative and liberal groups’ applications for tax-exempt status under 501(c)(4) for extra scrutiny, sometimes allowing their applications to languish for years. Political wrangling over tax exemption is nothing new. The case of the Charles E. Merrill Trust provides an interesting mid-20th century example of the way political influence was leveraged to change the tax code.

Charles E. Merrill (AC 1908), founder of Merrill Lynch & Company, attended Amherst College for two years. Even though he left before graduating, he remained devoted to Amherst College, attending many reunions and donating large sums of money, including paying the tuition of more than 300 Amherst students during his lifetime, funding the construction of on-campus faculty housing, and hosting the Amherst College Merrill Center for Economics at his estate in Southampton, NY. Merrill was equally generous to Amherst College in his will. In his will, Charles Merrill established the Charles E. Merrill Trust, which would exist for twenty years and distribute his estate (a large portion of which was his personal stake in Merrill Lynch & Co.) to various institutions and charitable organizations.

Amherst College stood to gain the largest single chunk of this trust fund—twenty percent of the total pool of money. As the tax code stood in 1956 when Merrill died, however, any interest from his limited partnership in Merrill Lynch & Co. stood to be, “taxed to the Trustees at the rates imposed on individuals as ‘unrelated business income’ even though all the uses are charitable.” [Letter to Senator Albert Gore, Sr., March 14, 1958, J. Alfred Guest Alumni Biographical File (1933)]. Interested parties at Amherst College—including politically-connected faculty and alumni—and Deerfield Academy, which was also a named beneficiary in the will, went into action, lobbying U.S. Representatives and Senators to change tax law.

The Amherst College Archives and Special Collections have a folder of letters and memoranda that document this campaign. One memo, dated March 11, 1958, details who is responsible for contacting which senator, with notes including the following for the person responsible for lobbying Senator Albert A. Gore, Sr. of Tennessee: “J.A.G. [J. Alfred Guest (AC 1933)] to ask Vic Johnson [Victor Johnson (AC 1938)] to go ahead, reminding Johnson that Maryville College in Tennessee has already received $50,000 from Charlie Merrill.” [March 11, 1958 memo, J. Alfred Guest Alumni Biographical File (1933)].] In his book The Checkbook: The Politics and Ethics of Foundation Philanthropy, Charles E. Merrill, Jr. suggests that House Majority Leader John W. McCormack was prompted to introduce a bill changing the tax code by an agreement that the Trust would fund a pet project for his friend Cardinal Richard Cushing, who was building a home for “wayward girls” near Boston [pg. 12]. Unfortunately, while we hold the grant records of the Charles E. Merrill Trust from September 1959 onward, we do not have the records of their earliest grants, so it is unclear whether the home was funded or not.

Ultimately, the US Congress approved a very narrow statue, Public Law 85-367, on April 7, 1958, which gave tax-exempt status to the funds for the Charles E. Merrill Trust. The Merrill estate is not mentioned by name in the law, but the language in the act is highly specific. To wit: “In the case of a trust (A) created by virtue of the provisions of the will of an individual who died after August 16, 1954, and before January 1, 1957…” and, “…the amendment… shall apply to taxable years of trusts beginning after December 31, 1955.”

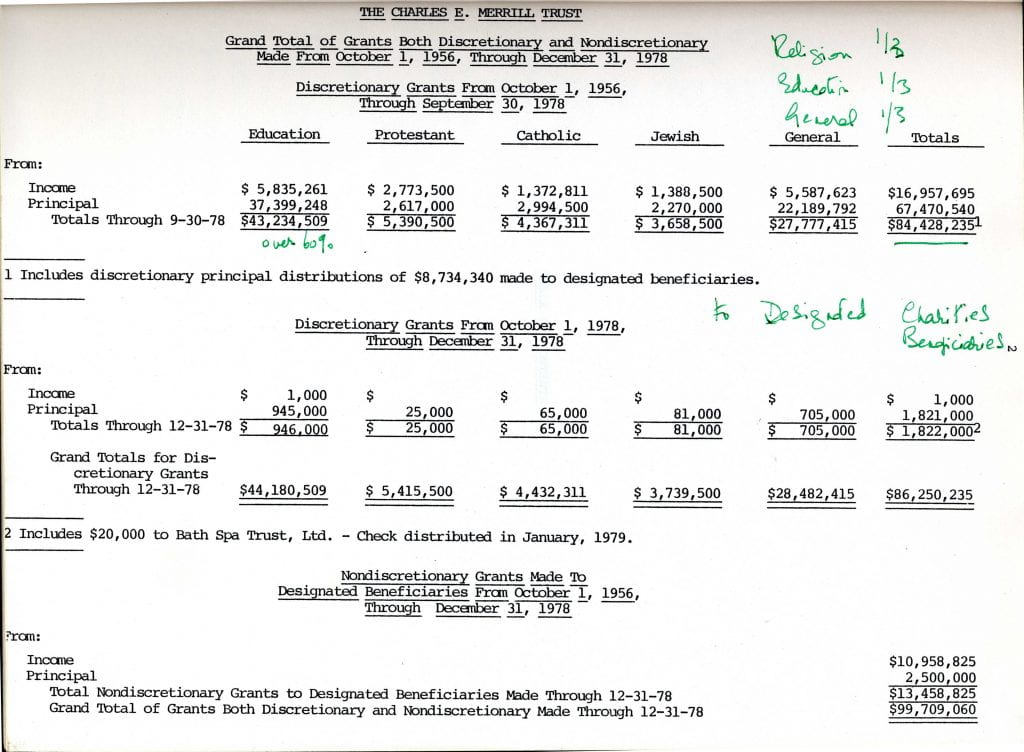

The Charles E. Merrill Trust went on to donate over 114 million dollars to various organizations—including Amherst College—during its twenty-three year existence (extended from the original twenty year time frame laid out in Merrill’s will). According to Charles E. Merrill, Jr., the Trust only spent an average of 2.8 percent of its income on overhead costs, apparently making quite effective use of its tax exemption.