Jim Steinman (AC 1969), the phenomenally successful composer, lyricist, Grammy-winning record producer, arranger and performer, was awarded an honorary degree at the Amherst College commencement this May.

(Photo: Amherst College Office of Public Affairs)

Steinman is still probably best known for penning such songs as “Bat Out Of Hell” and “Paradise By The Dashboard Light” on Meat Loaf’s album Bat Out of Hell—the second best-selling record of all time—and “I’d Do Anything for Love (But I Won’t Do That)” on Bat Out Of Hell II. But his work in musical theater is equally deserving of attention; for example, he wrote the lyrics in a collaboration with Andrew Lloyd Weber for Whistle Down the Wind (1996).

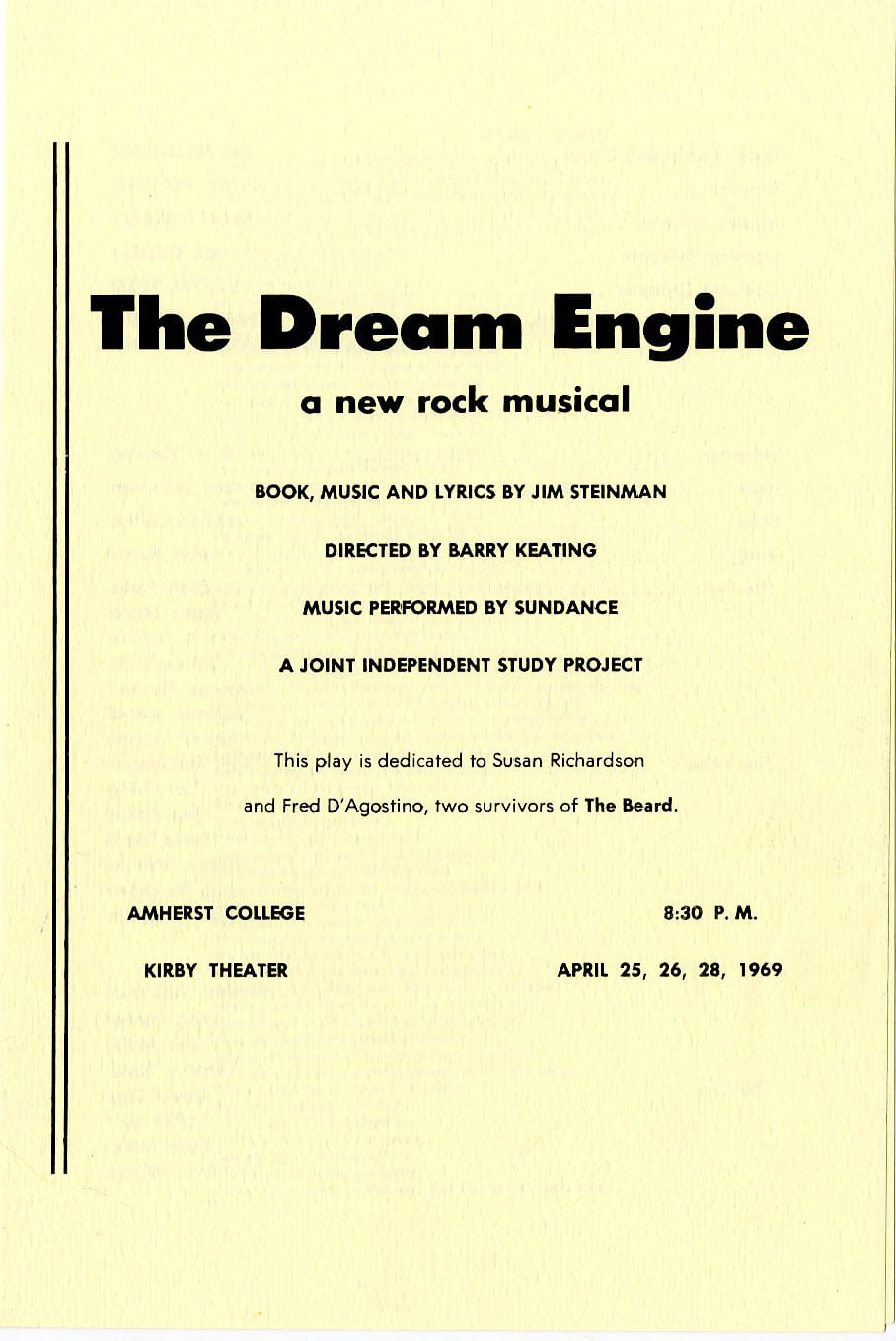

The hoop-la surrounding the return of a veritable musical superstar to Amherst made me wonder about what Steinman got up to while he was an undergraduate. Given his high-gothic sensibility and the generally turbulent nature of the ’60s when he was here, it’s not surprising that the answer is: quite a lot, actually. While at Amherst, Steinman indulged his passion for musical theater by writing a number of rather daring works. Most notable among them was The Dream Engine, a rock musical that Steinman wrote as an independent study project in his senior year.

Let’s have a look at this work, as documented in our Dramatic Activities Collection and our College Photographer’s Negatives Collection.

[Dramatic Activities Collection]

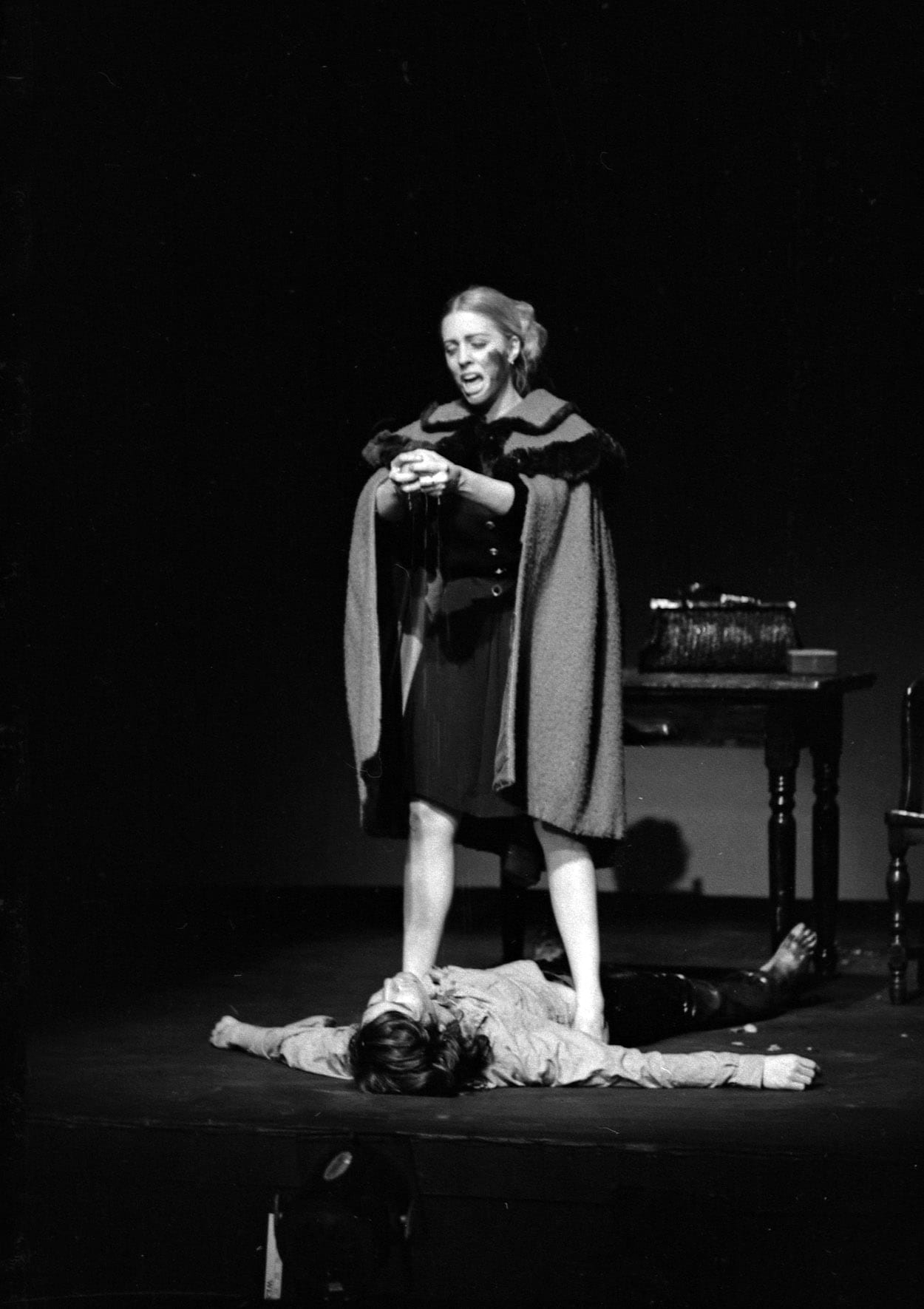

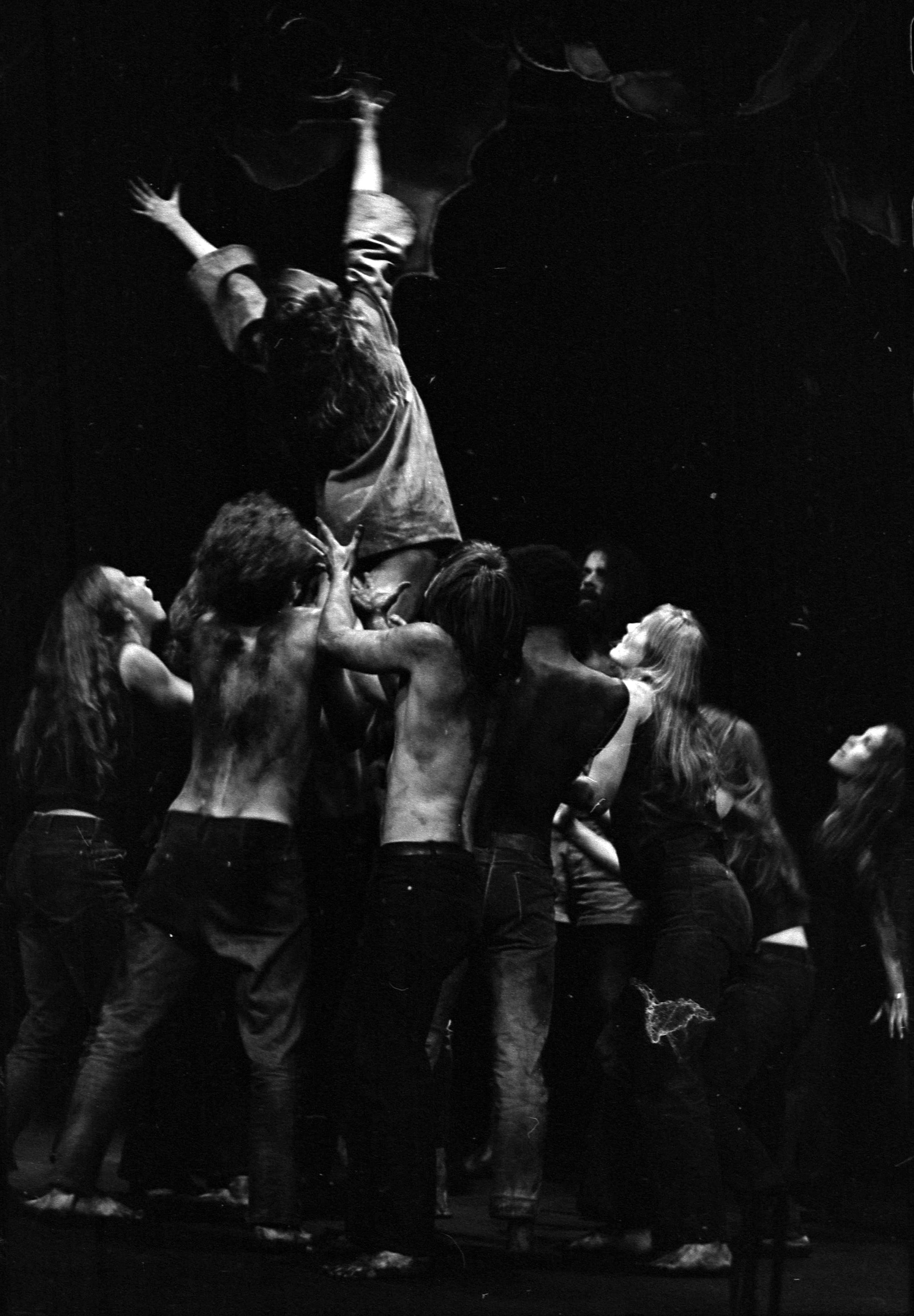

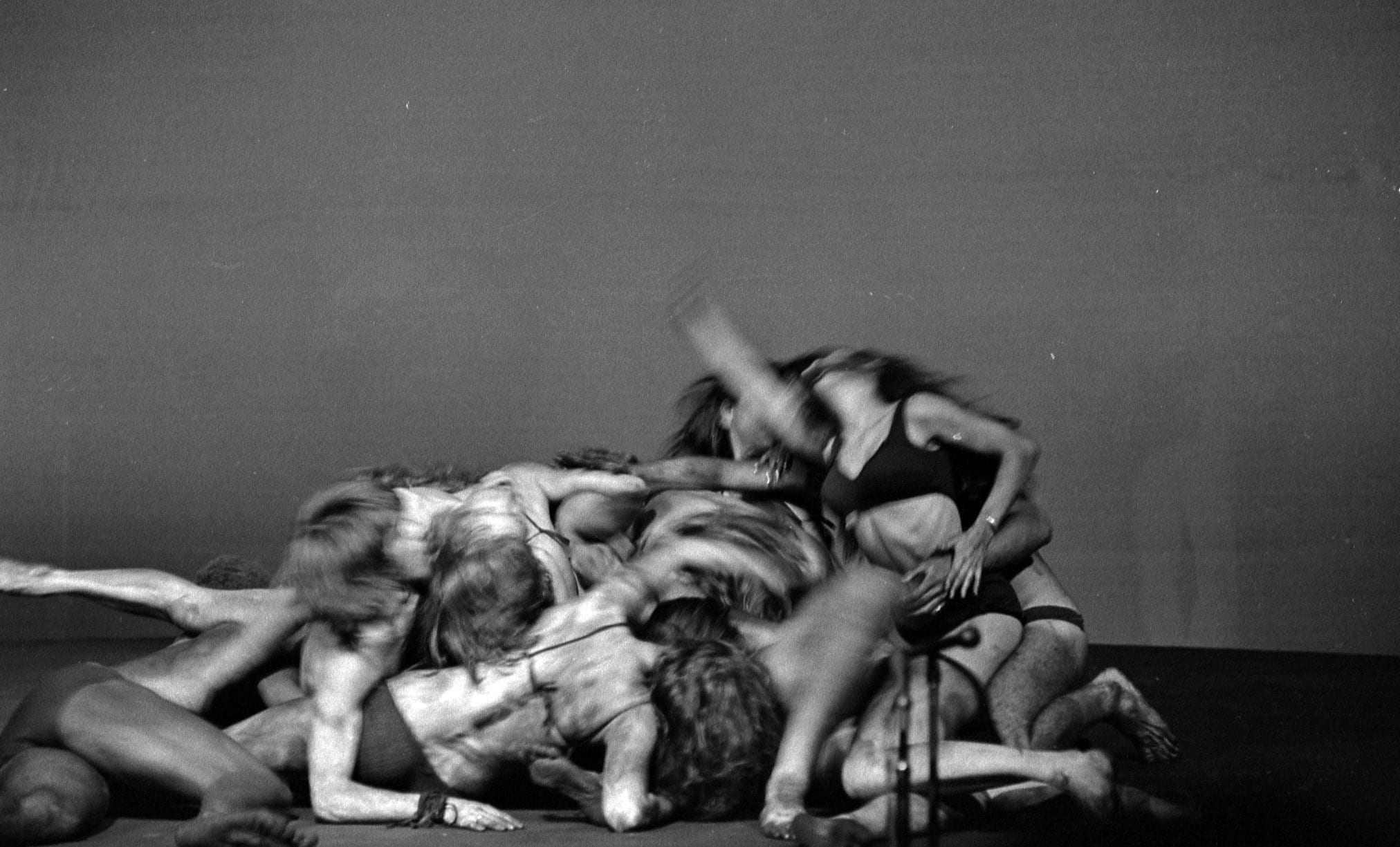

A tale of youthful rebellion culminating in revolution, The Dream Engine is set in the distant future and stars Steinman himself in the role of Baal, a young man who leads a group of wild boys called The Tribe. Baal falls in love with The Girl, whose parents (naturally) become pitted against him as mortal enemies. The final scenes of the opera depict a society in a cataclysmic revolution in which humanity reverts to a primitive state. Performances at Amherst College and Mount Holyoke College were sold out. (Excerpts from Steinman’s draft manuscript can be found on his web site, here.)

[This and following images: College Photographer’s Negatives Collection]

The Dream Engine caused a stir for its rather shocking depiction of societal conflict, which led in turn to a refusal by the college’s Independent Study Committee to allow its performance on a Sunday. “Blue Laws” at that time prevented public events like this from taking place unless they were “in keeping with the character of the Lord’s Day and not inconsistent with its due observance.” Accordingly, the Sunday performance had to be rescheduled to the following day.

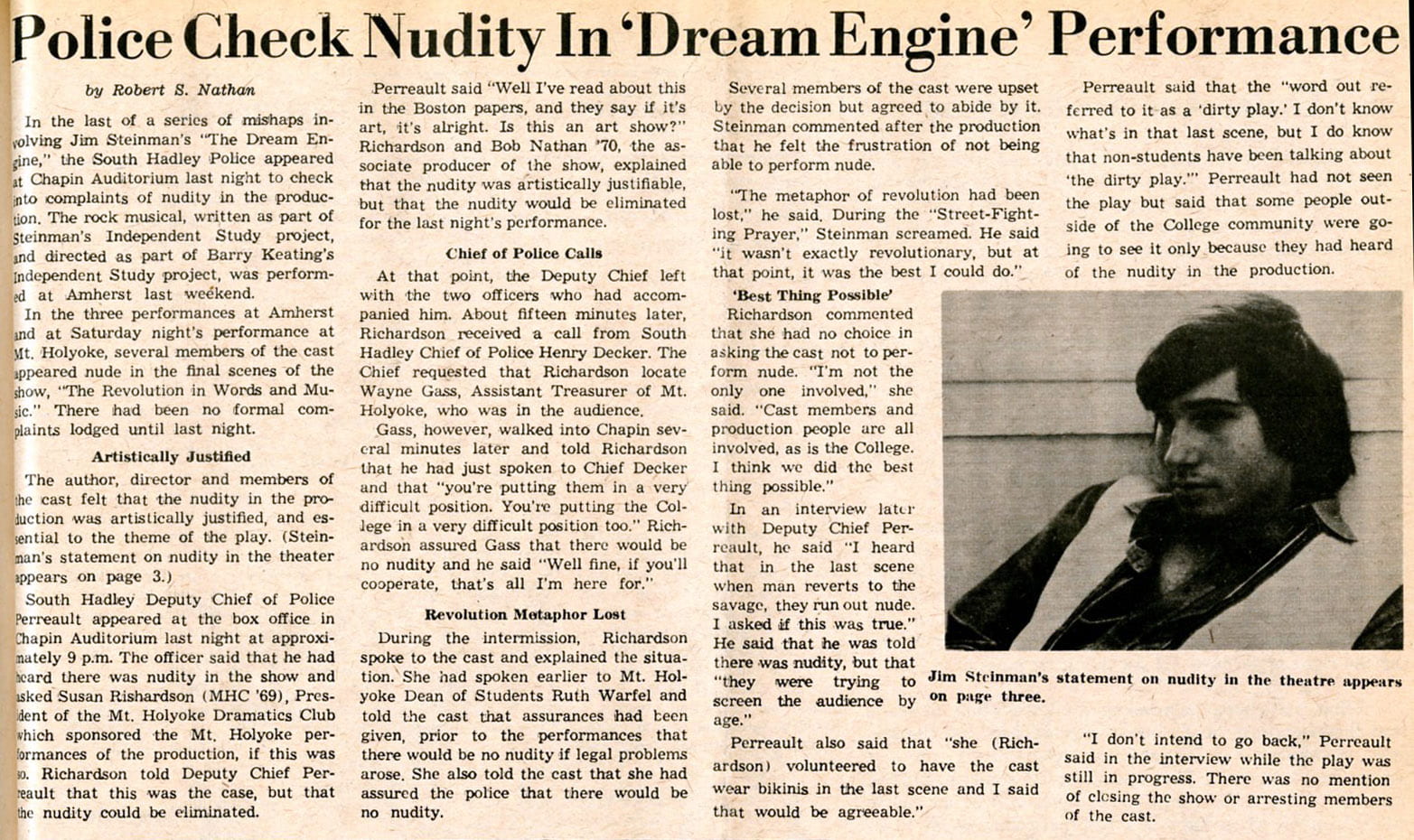

But Steinman’s play encountered much bigger problems for another reason. It called for some of the actors to appear nude in the final scenes (collectively called “The Revolution in Words and Music”). Apparently, the first three performances at Amherst’s Kirby Theater, as well as the first performance at Mount Holyoke College the following week, featured the nudity; there were no formal complaints. Only on May 4, 1969, the final night of performance at Mount Holyoke, did South Hadley’s Chief of Police feel compelled to investigate. According to news reports in the Amherst Student (see below), it appears that the police didn’t ban the nudity outright or threaten to shut down the performance; but simply by inquiring into the nature of the nudity (“They say that if it’s art, it’s alright. Is this an art show?”), the president of the Mount Holyoke Dramatics Club (which was sponsoring the performance) was induced to urge the actors to wear bathing suits instead.

Thus:

Steinman’s reaction to the last-minute decision to clothe the actors was blistering. As he insisted in the following defense published in a subsequent issue of the student paper, “the bare flesh helped make the ‘Revolution’ scenes exciting, moving and extraordinarily powerful.”

Steinman could take heart, however, that despite the obstacles encountered by his senior independent study project, it led to a major breakthrough for him. Joseph Papp, the renowned New York theatrical producer and director who founded the New York Shakespeare Festival as well as the Public Theater, saw the show and wished to bring it to New York immediately. While this never came to fruition, it did lead to a lifelong collaboration between Steinman and Papp.

This is a fantastic article about Jim Steinman and “The Dream Engine,” which has influenced my life like no other piece of theatre! Thank you for the great information and releasing these photos.