The records of the Amherst College Anti-Slavery Society provide an interesting glimpse into a formative period in College history. In addition to detailing the early history of activism about race at Amherst, they show the first strong challenge to the administration by students of the college.

The Anti-Slavery Society was founded on July 19, 1833, just two weeks after the formation of the Amherst College and Amherst Colonization Society. Both groups were intended as local chapters of state or national organizations, and their activities on campus mirrored the debate playing out on the national level.

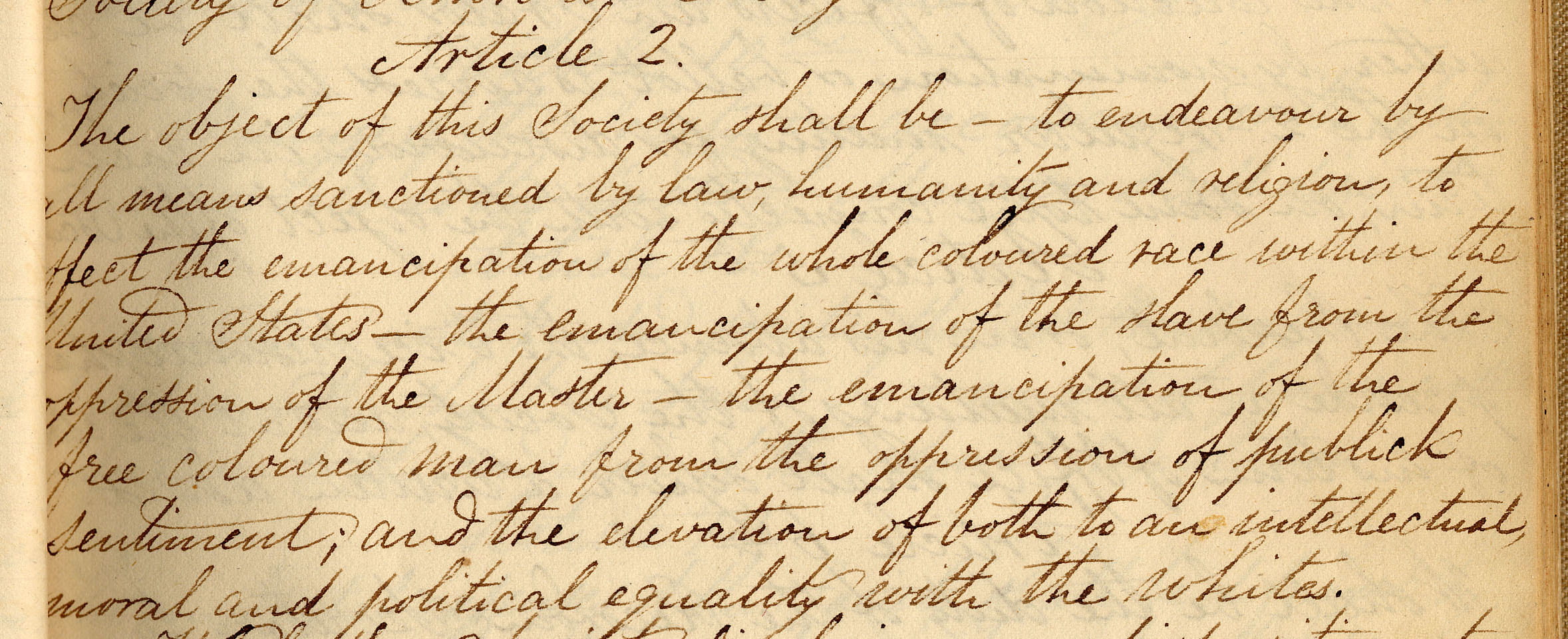

While the idea of colonization had been discussed for many years, it crystallized in 1816 with the formation of the American Colonization Society. The Society advocated the removal of free Black people from the United States to a colony in Africa. While the idea of colonization was critiqued from all angles right from the beginning, it remained the primary outlet for anti-slavery activity for many years and was very strongly supported in New England and in the Congregational Church with which Amherst was associated. The abolition movement, advocating the immediate emancipation of enslaved people, was most vocally championed by William Lloyd Garrison, who founded the first anti-slavery newspaper in 1831 and the New England Anti-Slavery Society in 1832. While the Colonization Society considered slavery an evil, it did not condemn slave-holders and advocated “gradual emancipation” with the free Black population being forced to move to Africa to eliminate the need for white and Black people to mix in society and interact as equals. Many enslavers supported colonization for the same reasons and out of fear that free Black people might incite rebellion among their slaves. In contrast, the Anti-Slavery Society considered slavery an individual sin on the part of every person in a slave-holding society, which necessitated the immediate end of slavery and every effort to bring Black people to a position of equality with white people. The constitution of the Amherst Anti-Slavery Society reflects this principle as seen in its second article (revised on Nov 24, 1834):

Article 2

The object of this society shall be – to endeavour by all means sanctioned by law, humanity, and religion, to effect the emancipation of the whole coloured race within the United States – the emancipation of the slave from the oppression of the Master – the emancipation of the free coloured man from the oppression of publick sentiment; and the elevation of both to an intellectual, moral and political equality with the whites.

Interestingly, the paragraph following disavows any use of violence or political force to achieve these aims and appeals instead to the moral duty of enslavers.

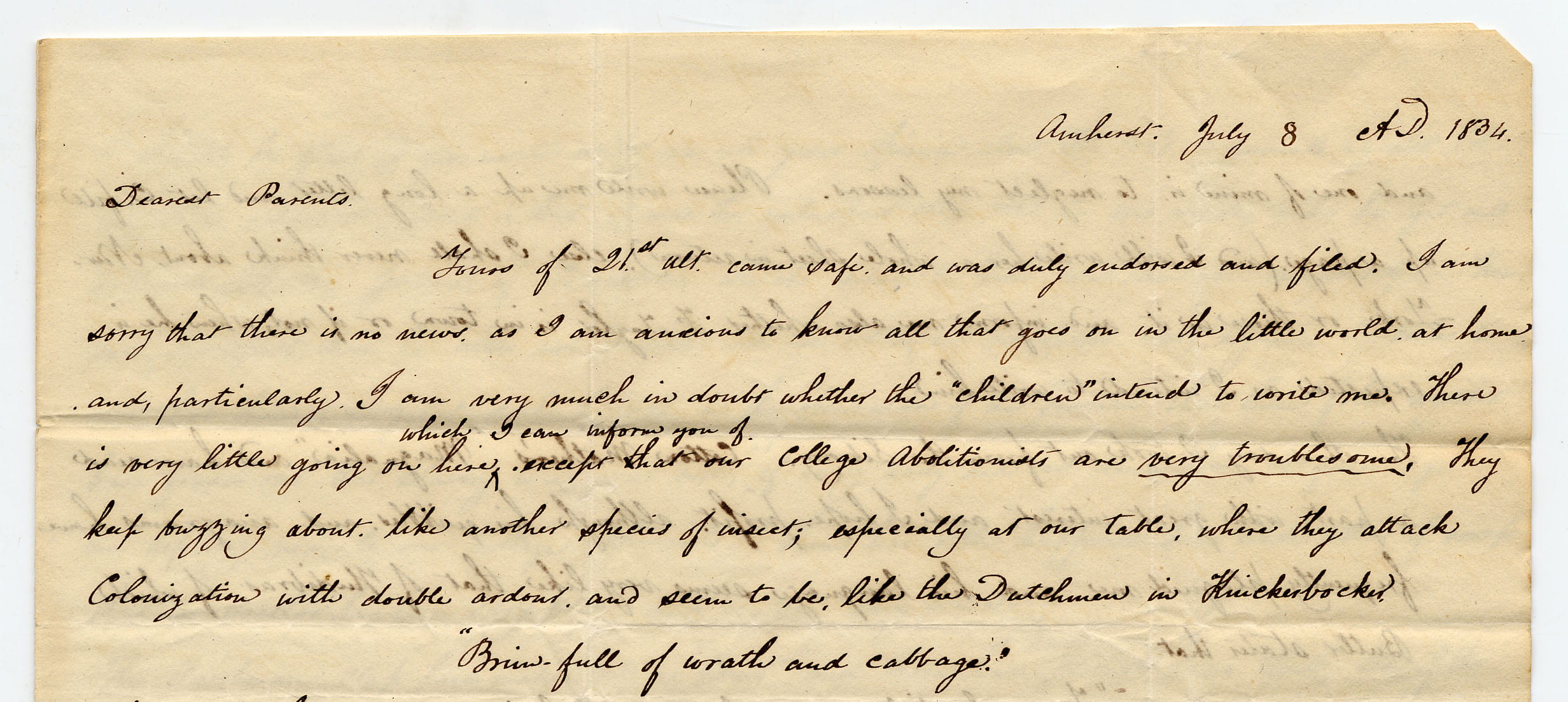

In the course of the first year and a quarter of the Anti-Slavery Society’s existence, it grew from the founding 8 members to a flourishing group of 78 (about one third of the student body) and held regular prayer meetings and debates focused on abolition and the various related events of the day. The students actively sought to recruit others, as mentioned in a letter home by an annoyed George Bacon, class of 1837 (and member of the Colonization Society) on July 8, 1834:

“…our College Abolitionists are very troublesome. They keep buzzing about like another species of insect; especially at our table, where they attack Colonization with double ardour and seem to be, like the Dutchman in Knickerbocker, “Brim-full of wrath and cabbage.”

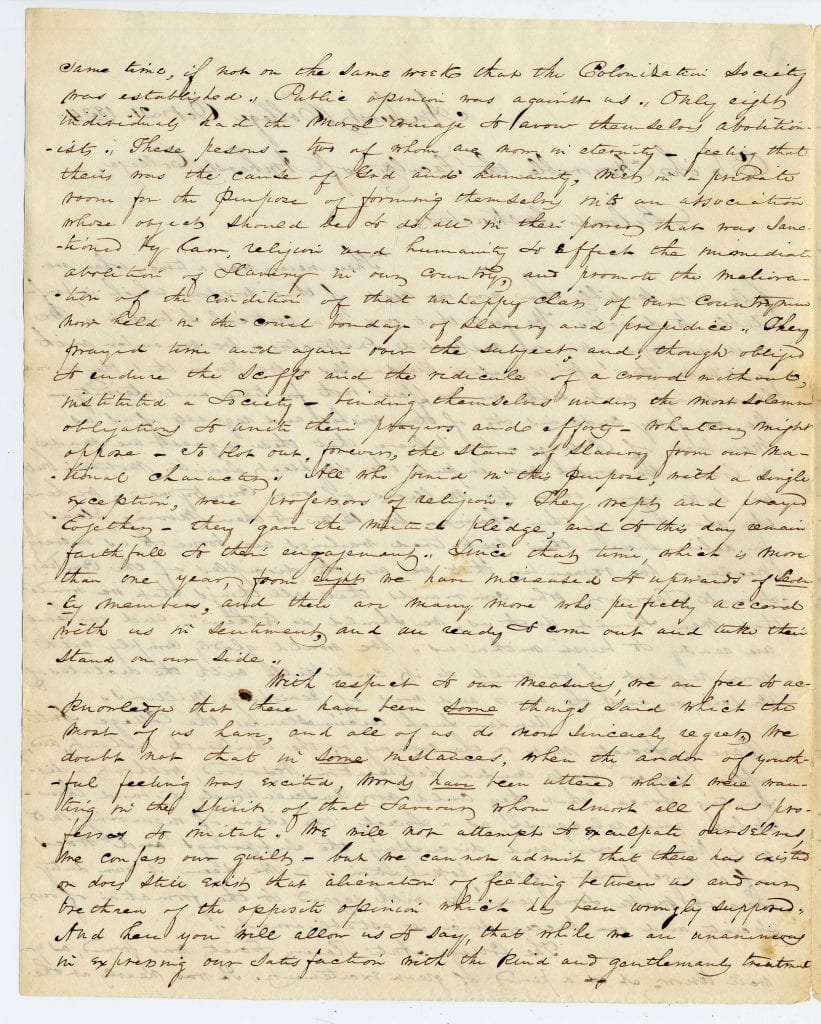

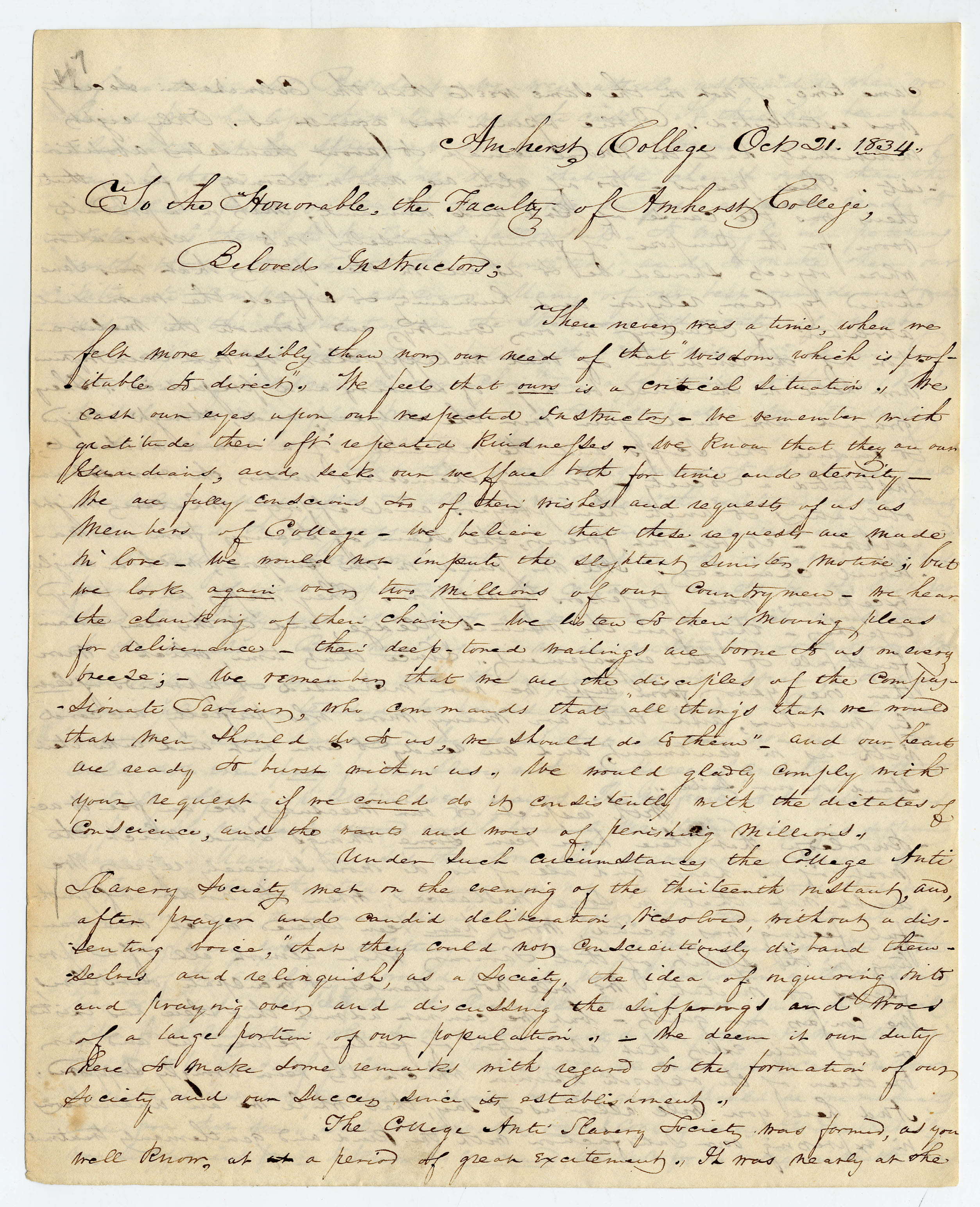

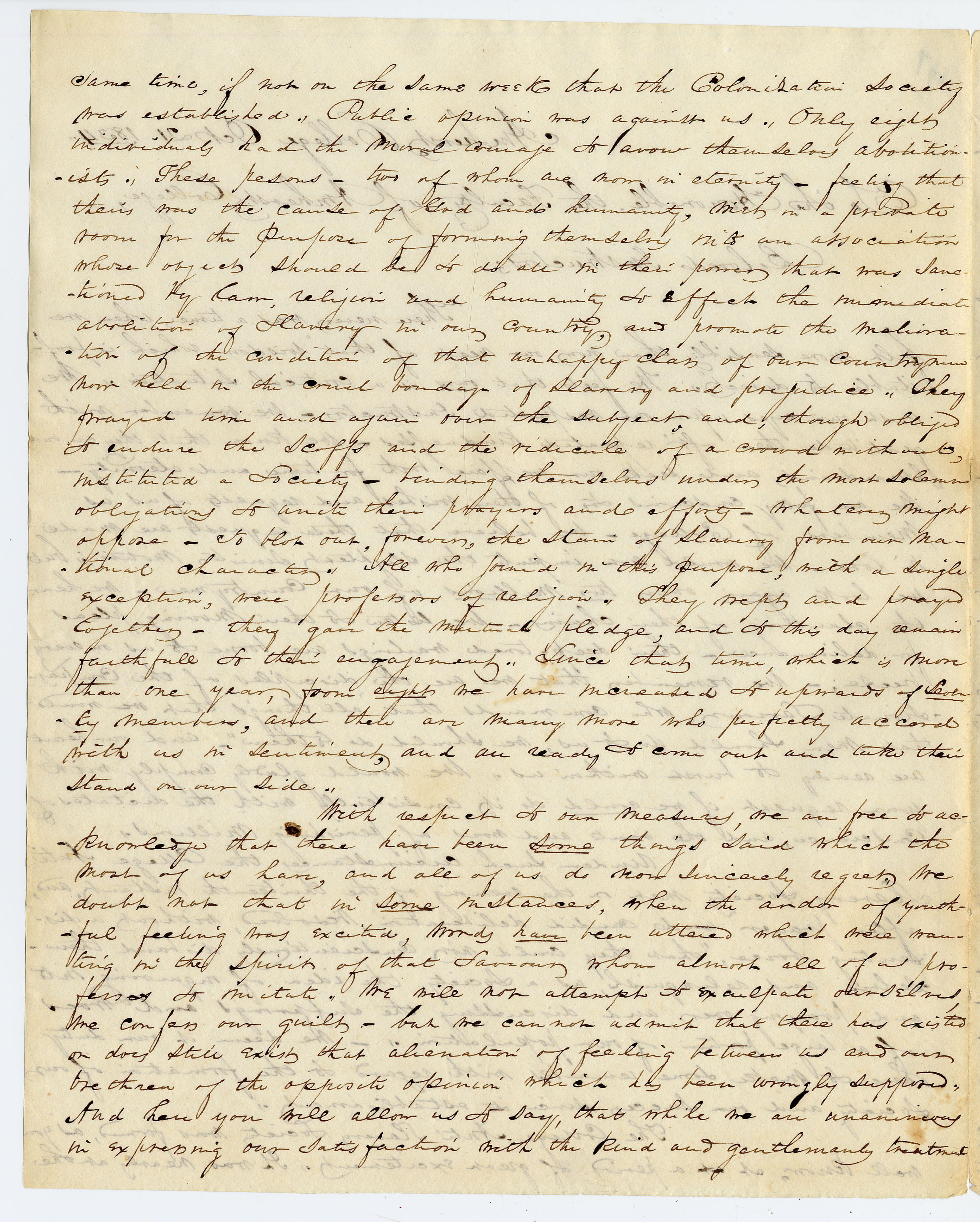

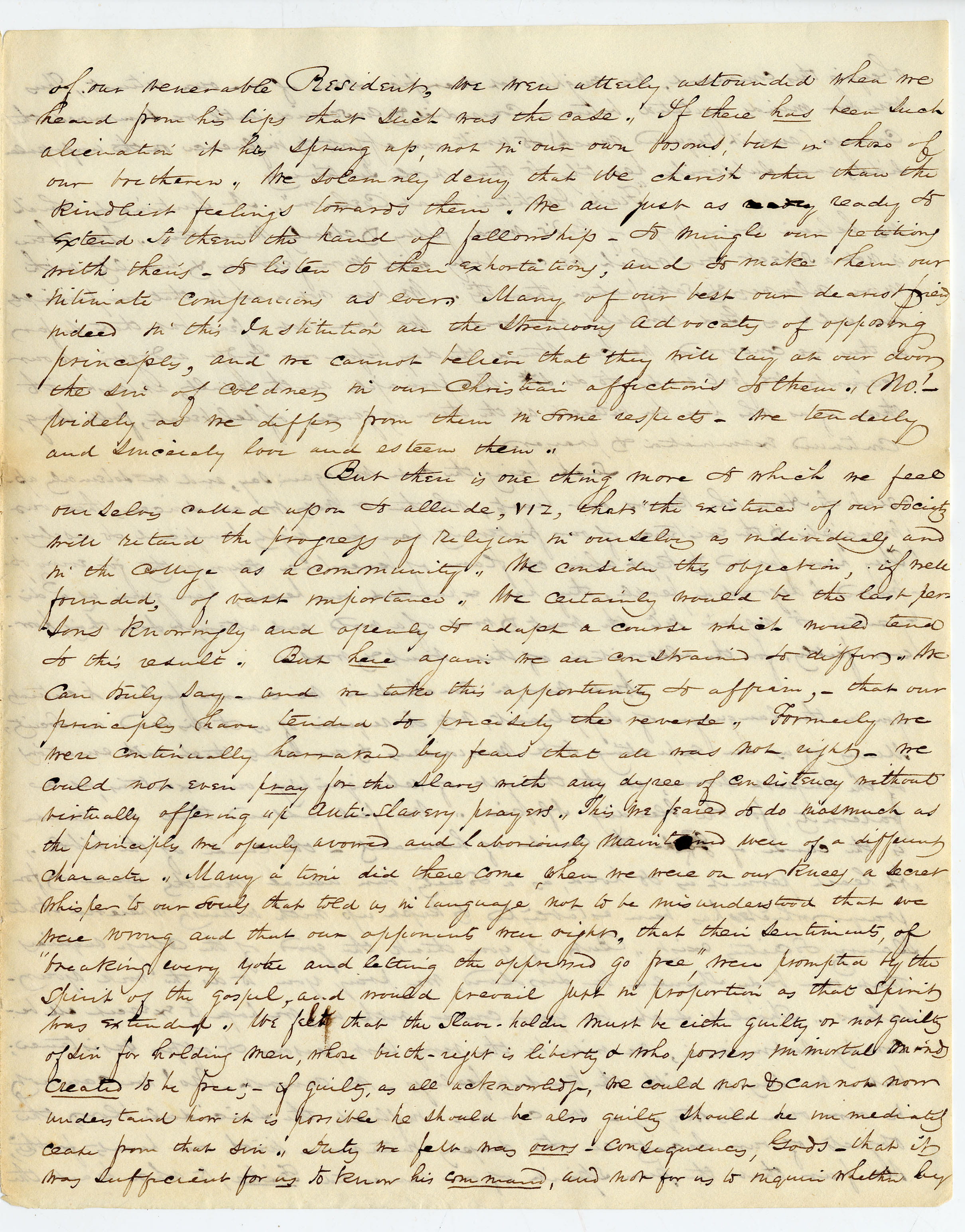

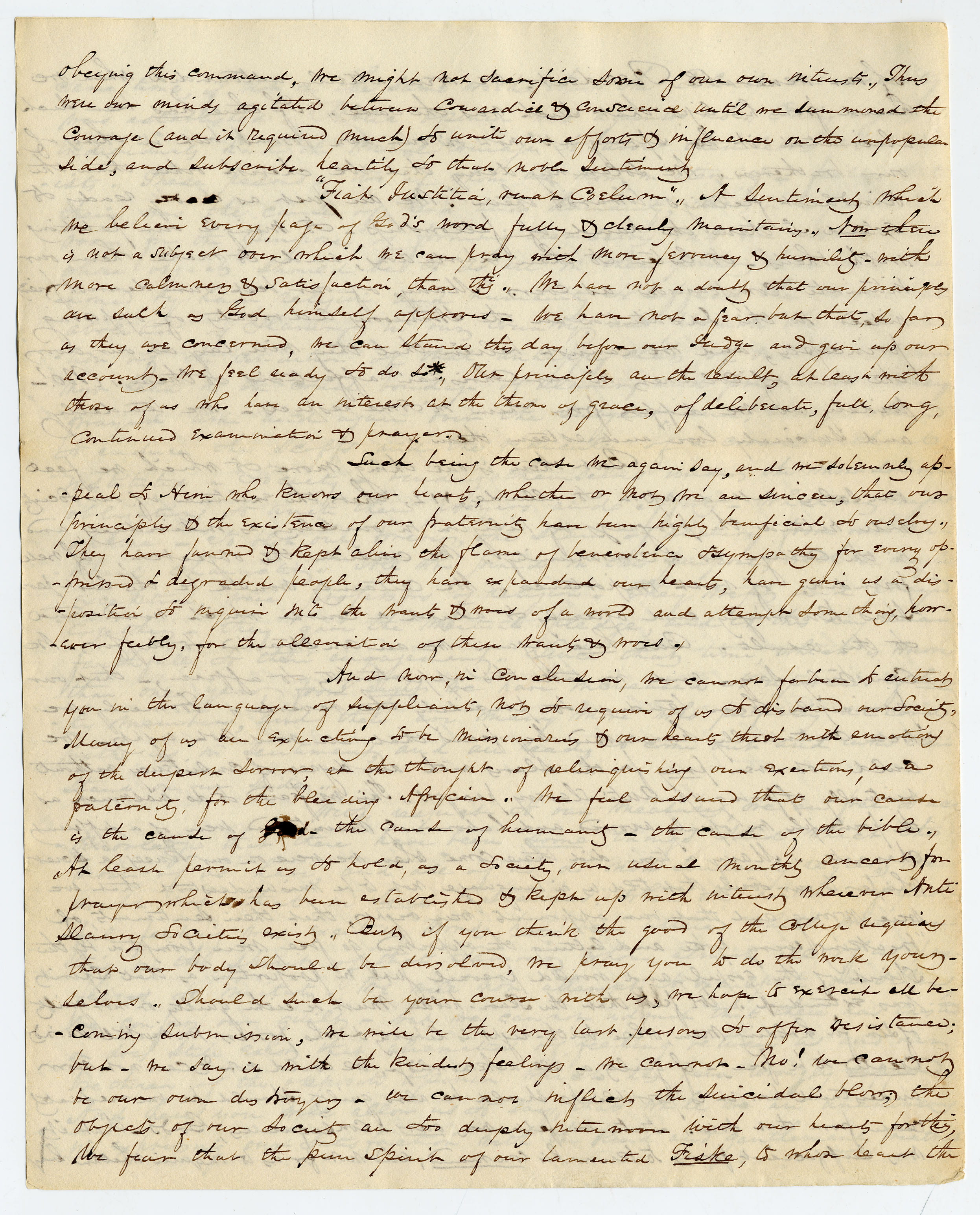

The College administration, many of whom belonged to the Colonization Society themselves, were also troubled by the Anti-Slavery Society, particularly in light of recent events at Lane Seminary in Ohio, where the quashing of anti-slavery activity among the student by the administration led the majority of the students at the seminary to leave the school. Amherst College had been founded and run, up to this time, as a very paternalistic and rigidly religious institution. The faculty maintained near absolute control of student life and students gave professors complete respect and deference. The increasing size of the student body and increasing diversity of religious and social backgrounds were already beginning to challenge this order and the schism and strong feelings around slavery prompted the faculty to attempt to regain control in October of 1834 by ordering both the Colonization Society and the Anti-Slavery Society to disband. The Colonization Society left campus with no protest and continued its existence as an organization based in the town of Amherst. The Anti-Slavery Society, on the other hand, had an extraordinary series of exchanges with the faculty protesting the decision even while using language that from modern prospective is humble and obsequious to the extreme.

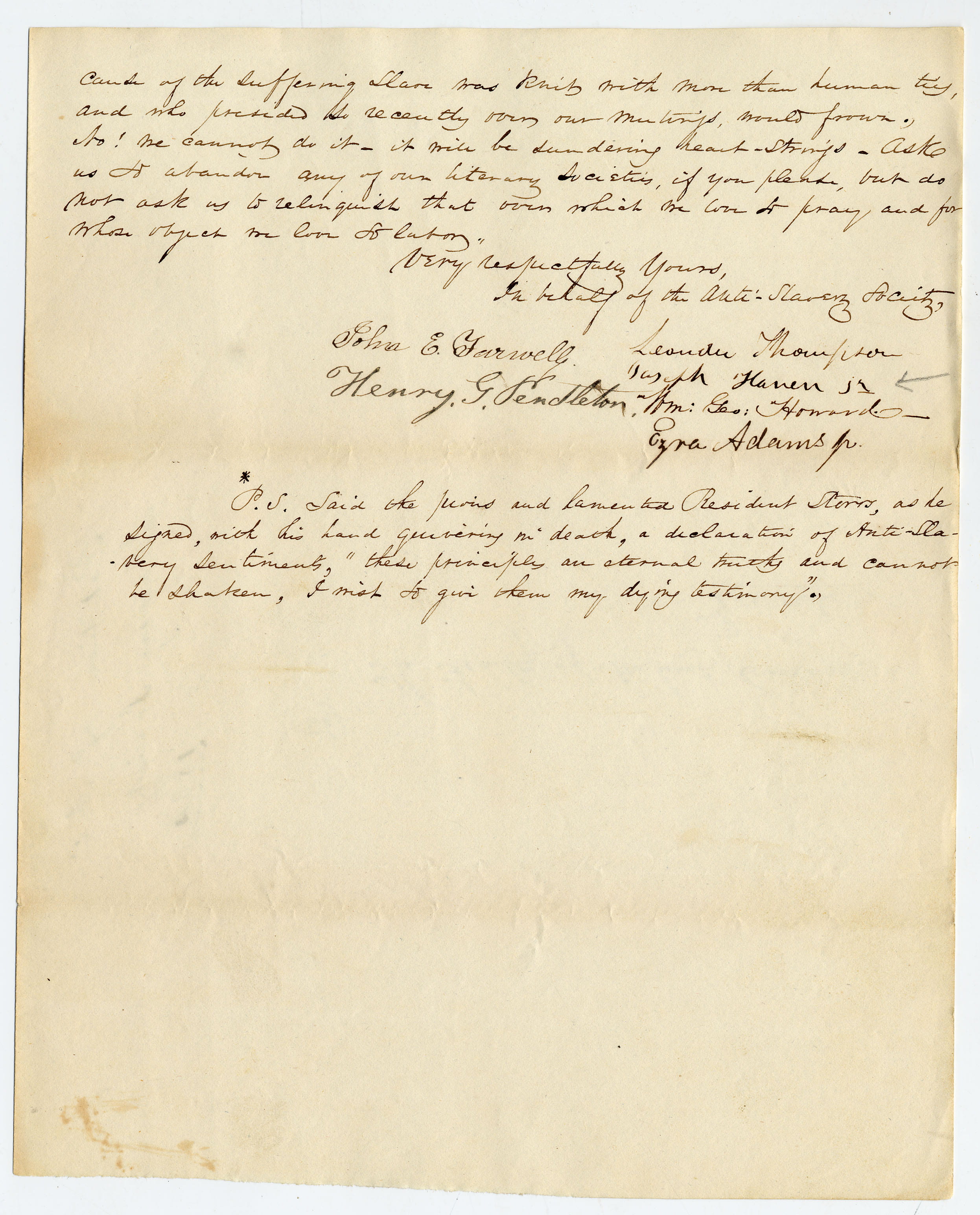

The students attempted to address the faculty’s stated concerns that the “the Society was alienating Christian brethren, retarding and otherwise injuring the cause of religion in the College, and threatening in many ways the prosperity of the Institution” (Tyler, History of Amherst College, p. 247) by giving an impassioned plea for the religious imperative of the anti-slavery cause and its positive impact on their own religious lives. The faculty was impressed by the respectful tone of the letter and they offered that the society could remain in existence if it held only prayer meetings, with no debates, no discussion, and no attempts to solicit new members. This was unacceptable to the students and in a final communication the faculty declared that the society “must cease to exist.”

As is often the case, the attention and sense of injustice surrounding the suppression of the Anti-Slavery Society brought more sympathy and attention to its cause. In the following years, events on the national and local level brought increasing support for abolition and increasing autonomy for the students at Amherst. One of these events was the beating of an anti-slavery student by a student from the south, Robert McNairy, on commencement day, 1835. The McNairy case turned public opinion at the college strongly in the direction of abolition. This sea change in campus sentiment led the faculty to grant permission on November 23, 1836 for a monthly “anti-slavery concert” (which would have included speeches and prayers) and in December of 1837 to grant “the request of the petitioners for an Anti-Slavery Society” (Tyler, p. 250). This reconstituted Anti-Slavery Society flourished for some years until its activity apparently ended in November of 1841. The decline of the society tracks the shift in emphasis, nationally and among members of the society, from a focus on individual moral persuasion to political action. The last debates of the Anti-Slavery Society were on the the topic “Is the present organization of the Liberty Party expedient?” and drew a large portion of the student body. In the last entry in the Anti-Slavery Society record book, on November 15, 1841, the secretary records this debate and the resulting decision in the affirmative as: “this we record as the decided triumph of Abolition over Slavocracy in this institution.”

_______________________________

This summary of Anti-Slavery Society at Amherst College is heavily indebted to the excellent student thesis by Robert J. Brigham, Class of 1985, titled, Amherst College: A Pious Institution’s Reaction to Slavery, 1821-1841.

Other sources:

Anti-Slavery Society Records, 1833-1842 in Clubs and Societies Collection (box 1, folders 18-20)

Correspondence regarding abolition of Anti-Slavery Society, 1834 Oct – 1835 Feb in Amherst College Early History Manuscripts and Pamphlets Collection (box 1, folders 47-51)

George Bacon letter to parents, 1843 Jul 8, in Historical Manuscripts Collection (box 3, folder 28)

The Anti-Slavery Movement in Hampshire County, Amherst College thesis by James C. Cochrane, class of 1946.

W. S. Tyler, History of Amherst College during its first half century, 1821-1871. Springfield, MA: C. W. Bryan, 1873.

3 thoughts on “Amherst College Anti-Slavery Society”