In the fall of 2011 we mounted an exhibition of Native American materials housed in the Archives & Special Collections to coincide with an extended visit from Fred Hoxie, a specialist in Native American history. Professor Hoxie graduated from Amherst College in 1969 and returned to campus as the 2011 Frost Fellow, sponsored by the Friends of Amherst College Library. While Native American history and culture is not one of our greatest strengths, the collection does contain a few gems.

Amherst College holds an excellent copy of the three-volume History of the Indian tribes of North America, with biographical sketches and anecdotes of the principal chiefs. Embellished with one hundred and twenty portraits, from the Indian gallery in the Department of war, at Washington by Thomas L. McKenney and James Hall issued between 1836 and 1844. More information about the fascinating story of this book and access to a fully digitized set of this work can be found at the University of Washington. The 121 hand-colored lithographs in this work present both a remarkable glimpse into nineteenth-century views of Native Americans and an example of the height of American printing technology in the 1830s and 40s. It’s simply a beautiful work of art:

One of the portraits included in this work is of Sequoyah, the man who single-handedly invented a writing system for the Cherokee language. Here he is shown with the syllabary he developed.

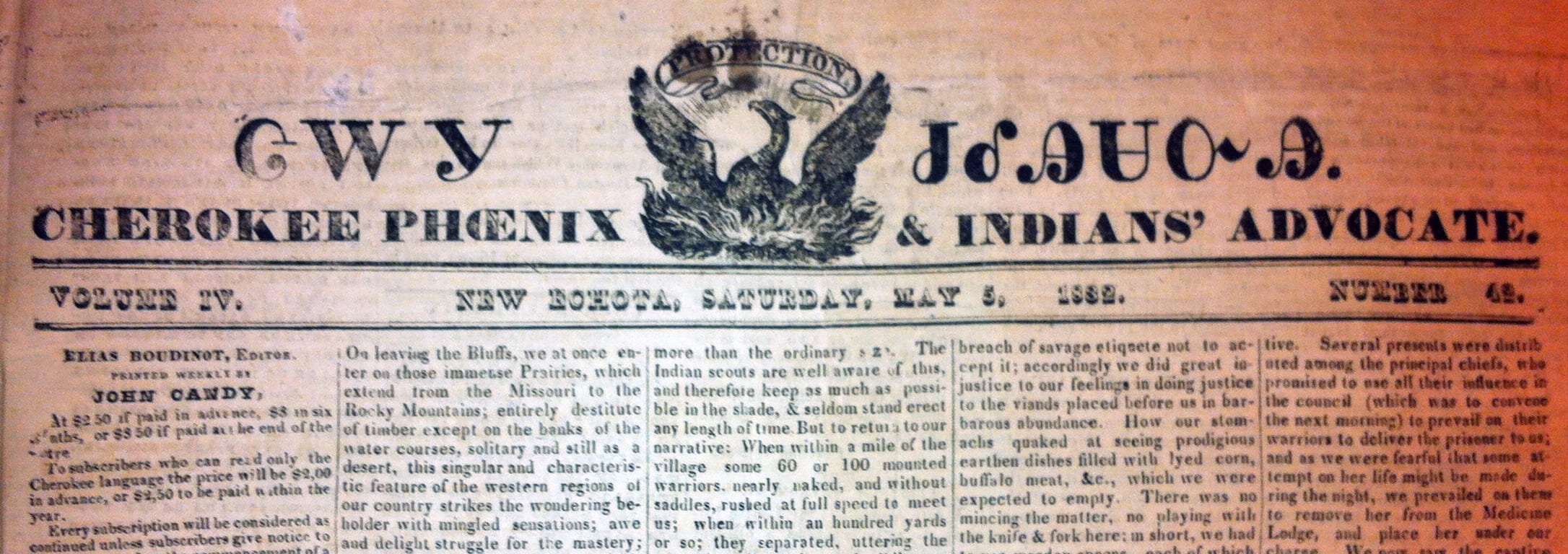

Sequoyah’s system is a “syllabary” because he developed symbols to represent each spoken syllable in the Cherokee language rather than an alphabet of characters that are combined to form different syllables. The Cherokee officially adopted Sequoyah’s writing system in 1825 and the missionary Samuel Worcester created the first Cherokee printing type in 1828. The typeface was used to print The Cherokee Phoenix, a newspaper dedicated to the news and events of concern to the Cherokee nation during a time of tremendous upheaval, to put it mildly. I was amazed and delighted to discover that we have two issues of The Cherokee Phoenix in our collections.

Shortly after the paper began, the name was expanded from Cherokee Phoenix to Cherokee Phoenix and Indians’ Advocate, to signal that the paper intended to advocate for the rights of all the native people of North America. The paper ceased publication in 1834. The Digital Library of Georgia includes what appears to be a complete set of the paper under both titles from 1828 through 1834. Efforts were made to revive the paper throughout the nineteenth century; it is now published by the Cherokee Nation and current issues are available online at http://www.cherokeephoenix.org.

The newspaper was printed in both English and Cherokee, but we recently purchased three books printed almost entirely in the Cherokee language.

Samuel Worcester relocated from Georgia to Park Hill, Oklahoma where he established a new mission and a new press to serve the Cherokee forced west on the Trail of Tears. He produced these translations with Stephen Foreman, a missionary whose mother was Cherokee. These three volumes complement the volumes of scripture translated into the Choctaw language already in the collection.

We hold many other books that relate to the history and culture of Native Americans, including James Adair’s The History of the American Indians (London, 1775), Samuel George Morton’s Crania Americana; or, a Comparative View of the Skulls of Various Aboriginal Nations of North and South America (Philadelphia, 1839), Samson Occam’s A Sermon at the Execution of Moses Paul, an Indian (London, 1788). We also have a very fine set of Edward S. Curtis’s monumental photographic work, The North American Indian Being a Series of Volumes Picturing and Describing the Indians of the United States and Alaska. In addition to the three translations pictured above, we also recently acquired The Lost Journals of Sacajewea — a beautiful collaboration between Debra Magpie Earling and book artist Peter Koch.

I would like to transcibe this article into Cherokee, strictly for my pleasure.

Can you direct me to the nearest syllabary?

I should have included this link in the original post. Amherst doesn’t own a copy, but Columbia University has made theirs available online:

https://ldpd.lamp.columbia.edu/omeka/exhibits/show/plimpton/early-modern/item/159

It’s also worth noting that Columbia’s copy of the Syllabary was a gift from George A. Plimpton who graduated from Amherst College in 1876. The collection of French and Indian War materials he donated to Amherst will be the subject of a post here sooner or later:

http://asteria.fivecolleges.edu/findaids/amherst/ma195_main.html