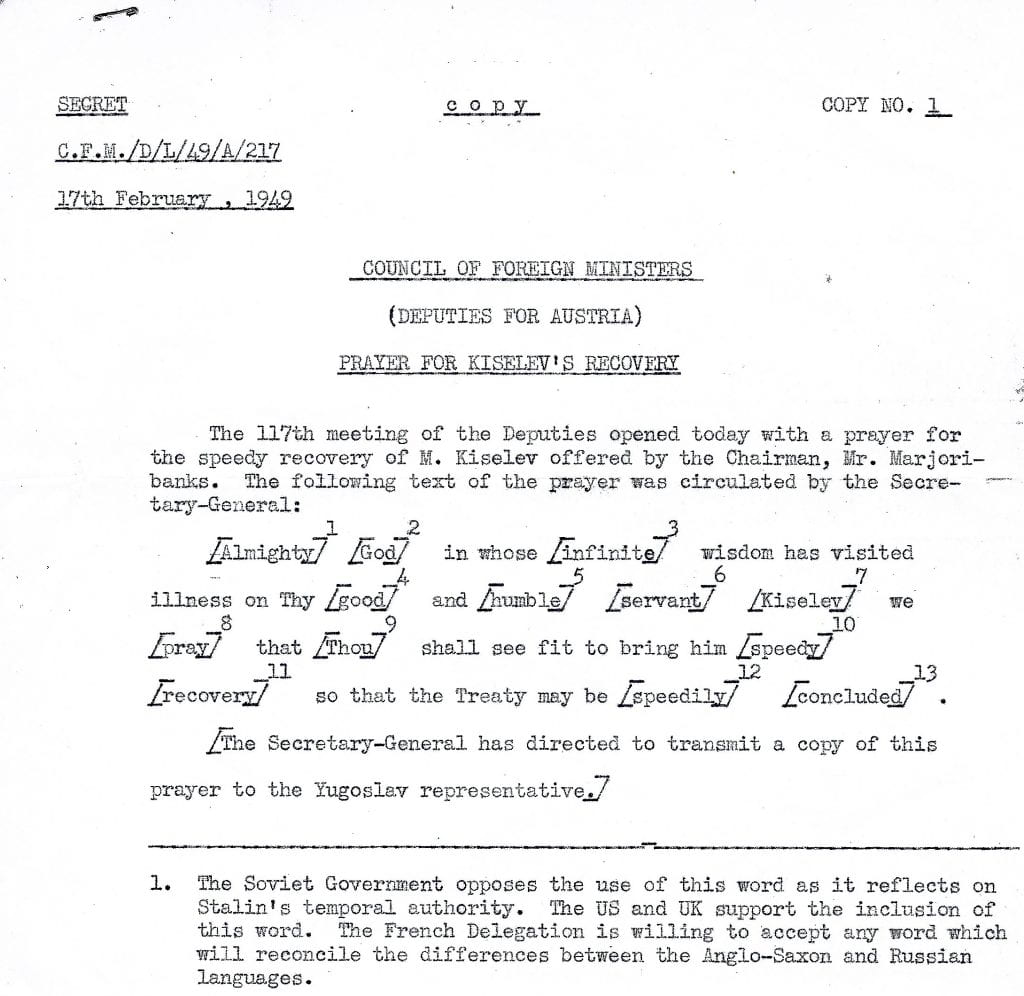

Buried in the papers of Willard L. Thorp, who was at the time Assistant U.S. Secretary of State for Economic Affairs and U.S. delegate to the United Nations Economic and Social Council, we found this puzzling “secret” document dated February 17, 1949. In reading the heavily footnoted “Prayer for Kiselev’s Recovery,” we realized that we had found a rare recorded instance of edgy, high-level diplomatic humor. The document pretends to be a secret memorandum circulated to members of the Council of Foreign Ministers in response to the illness of a top-level Russian diplomat. Formed in 1945, the Council of Foreign Ministers gave representatives of the Four Powers (Russia, France, the United Kingdom, and the U.S.) a forum for crafting peace settlements among and between European countries in the aftermath of World War II. Appreciating this high-stakes humor requires some close reading, as well as some knowledge of both the tenets of Marxism and the course of post-war diplomacy.

The framework of a prayer provides a marvelous opportunity for a series of not-so-subtle digs at Marxism, which supplied much of the ideological foundation of the Soviet state. Arguing that religion functioned only to make more tolerable the oppressions of class society, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels had asserted that “Communism abolishes eternal truths, it abolishes all religion, and all morality… it therefore acts in contradiction to all past historical experience.”* In the fictional debate over the crafting of this simple “prayer,” which takes place in the fourteen (!) footnotes, the representative of the U.S.S.R. therefore feels compelled to object to every word suggestive of belief in divinity or religious doctrine (notes 1, 2, 3, 8). Religious expression had indeed come under brutal attack during the first decades of Soviet rule in Russia: most churches were shut down or destroyed and clergy suffered persecution. Stalin had relaxed religious repression in the 1940s, when total mobilization for the war against Germany demanded the full cooperation of all sectors of society.** Without that “thaw,” it might not have been possible to poke fun at the Soviet state’s rejection of religion; the topic would have been too morbid—too real—to be amusing.

The framework of a prayer provides a marvelous opportunity for a series of not-so-subtle digs at Marxism, which supplied much of the ideological foundation of the Soviet state. Arguing that religion functioned only to make more tolerable the oppressions of class society, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels had asserted that “Communism abolishes eternal truths, it abolishes all religion, and all morality… it therefore acts in contradiction to all past historical experience.”* In the fictional debate over the crafting of this simple “prayer,” which takes place in the fourteen (!) footnotes, the representative of the U.S.S.R. therefore feels compelled to object to every word suggestive of belief in divinity or religious doctrine (notes 1, 2, 3, 8). Religious expression had indeed come under brutal attack during the first decades of Soviet rule in Russia: most churches were shut down or destroyed and clergy suffered persecution. Stalin had relaxed religious repression in the 1940s, when total mobilization for the war against Germany demanded the full cooperation of all sectors of society.** Without that “thaw,” it might not have been possible to poke fun at the Soviet state’s rejection of religion; the topic would have been too morbid—too real—to be amusing.

While diplomatic negotiations were indispensable in post-war Europe, with its ravaged economies and millions of dislocated persons, the writer of the “prayer” also takes undisguised delight in poking fun at the cumbersome and often petty nature of diplomatic talks. Picking a favorite jab is not easy: would it be the fact that the French cannot offer an opinion on the word “infinite” without consulting the Institute of Cartesian Physics in Paris (note 3)? or the assumption that a committee would have to be formed to discuss the spelling of Kiselev’s name (which was sometimes written “Kisselev”) (note 7)?

Beneath these jibes are a series of references to the emergent Cold War stances of the United States and Russia. Austria figures large here because in the year it was written (1949), the Four Powers nearly came to terms on how to end the occupation of Austria. According to the scholar Audrey Kurth Cronin, treaty negotiations over Austria failed in 1949 primarily because members of the U.S. Department of Defense and those with the State Department could not agree on how to negotiate with the U.S.S.R.*** The “prayer” appears to ridicule hardline rhetoric by painting the U.S. delegation as utterly unable to pass up an opportunity—no matter how miniscule or nonsensical—to provoke the Soviet deputies (notes 4, 10, 14 ). Mentions of neighboring Yugoslavia appear nearly as often. Not only were Yugoslavia’s unsettled issues deeply intertwined with those of Austria, but, in soon-to-be typical Cold War fashion, the U.S. delegates rush to object to anything Yugoslavia might want or get (including a copy of this memorandum!) as a symbol of their opposition to all things connected to the U.S.S.R. (note 14). 1949 marked the year when the lines of Cold War politics began to harden. One wonders if such jokes existed—or were even conceivable—ten or fifteen years hence.

Readers (especially students of post-war and Cold War politics) will surely find even more to chuckle at or reflect on; we hope you will let us know what we may have overlooked or misunderstood.

The Willard L. and Clarice Brows Thorp Papers are the last of three collections currently being processed at the Archives with the help of a grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission. The other two, the Charles L. Kades Papers and the Karl Loewenstein Papers are available for research, as the Thorp Papers soon will be. For more collections at Amherst documenting post-war diplomacy, see the subject guide to our Collections.

*Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto (Signet Classic Edition) (New York: Penguin Putnam, 1998), 74. [First published in 1848.]

** Thomas Hopko and Hilarion Alfeyev, “The Russian Orthodox Church” in The Encyclopedia of Religion, edited by Lindsay Jones (2nd ed., vol. 12) (Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2005), 7941-7947. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 19 Dec. 2011.

***Audrey Kurth Cronin, “East-west negotiations over Austria in 1949: Turning-point in the Cold War,” Journal of Contemporary History, vol. 24 (1989): 129-131; 134-138. It took until 1955 for the powers involved to reach an agreement on Austria’s future.