Nearly every student who has attended Amherst College is represented in the Alumni Biographical Files collection, which documents the lives of alumni from 1821 to the present. Biographical files may contain as little as basic information about a student’s enrollment dates at the college, or may contain many folders of items related to alumni lives and careers, depending on how much material has been gathered or donated for each student. Calvin Coolidge’s “bio file” is equal in size to a small manuscript collection, while others contain just enough for one folder.

Nearly every student who has attended Amherst College is represented in the Alumni Biographical Files collection, which documents the lives of alumni from 1821 to the present. Biographical files may contain as little as basic information about a student’s enrollment dates at the college, or may contain many folders of items related to alumni lives and careers, depending on how much material has been gathered or donated for each student. Calvin Coolidge’s “bio file” is equal in size to a small manuscript collection, while others contain just enough for one folder.

Questions and requests from researchers frequently send us to these biographical files, giving us the opportunity to learn about some fascinating Amherst alumni. Looking into these files allows us to rediscover their contributions and learn something about the social and cultural contexts for their work. One of the alumni who came to our attention this way was educator Charles Henry Moore.

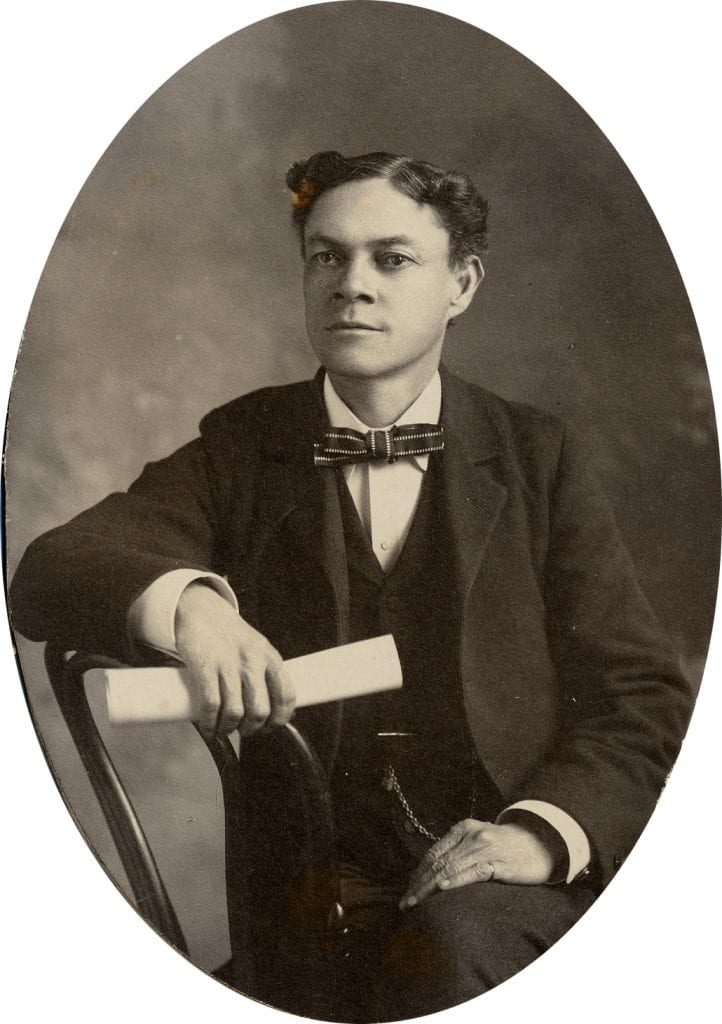

Charles Henry Moore, class of 1878, was one of the first black graduates of Amherst College. His name is still associated with milestones in African-American education in the South. This is particularly true in Greensboro, North Carolina, where the Charles H. Moore elementary school is named in his honor and where he was instrumental in the establishment of the North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University in 1891 (then called The Agricultural and Mechanical College for the Colored Race). Writing sometimes under the name “Justice,” Moore crusaded in print and on the ground against racial prejudice in the South, particularly in the field of education.

Very little is known of Charles Moore’s early life. From Amherst College questionnaires now found in his biographical file, we know that he was born on June 6, 1855 in Wilmington, North Carolina, the son of a Scotch-Irish father also named Charles, and mother Emily, who Moore listed as “colored.” There are conflicting secondary accounts of Moore’s childhood and of how he came to Amherst, but it seems that George Kidder, associated with Amherst, was largely responsible for his attendance. The deRosset family, employers of Emily Moore, had brought the promising student to Kidder’s attention. According to one story, before Charles Moore left North Carolina for Massachusetts, he promised Fannie deRosset that he would return to the South and “direct his efforts toward educating his people.”*

Whatever the reason, Moore returned to North Carolina following his graduation from Amherst in 1878, and committed to working against educational and financial inequality. In addition to his work with the North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, he was the first principal of a “negro graded school” in the state, helped to organize the Negro North Carolina Teachers’ Association, became the regional director of the Julius Rosenwald Fund, in which role he helped to build schools for black students in rural areas, helped establish the L. Richardson Memorial Hospital and worked with Booker T. Washington as vice-president of the national Negro Business League.

Moore’s 1916 inspection and report on rural schools in North Carolina was groundbreaking, and showed that thousands of public dollars earmarked for black education had gone instead to build schools, hire teachers and increase resources for white students. The work of researching the report had not been easy. Moore traveled more than 12,000 miles, from county to county, studying the conditions of schools, speaking with superintendents and advocating for equal education of black children. In some locations, opposition to public money for black education was so fierce that he received threats and sometimes had to “flee at night.”* His work not only resulted in more support from white officials and better educational opportunities for Southern blacks, but encouraged members of these communities to hope and work for better lives for themselves and their children. “Wherever I have gone,” Moore wrote, “I have endeavored to commit our people to the policy of self-help, and be it said to their credit, they have become aroused and enthusiastic.” Charles Henry Moore died at the age of ninety-seven in 1952, on the eve of the Second Reconstruction, having begun his life in a pre-emancipation South. He is remembered as an important crusader against the negative social and educational legacies of slavery.

Further information on Moore’s life and on other alumni can be found in the Alumni Biographical Files collection, arranged by class year. The finding aid for this collection includes appendixes that list unpublished manuscripts; academic class notes; and essays and orations from 1821-1889 in the Alumni Biographical Files and Class Shelves.

* Arnett, Ethel S., For Whom Our Public Schools Were Named, Greensboro, North Carolina, Piedmont Press, 1973

I attended Charles H. Moore Elementary School in Greensboro. A painting of him was in the hallway near the school entrance. My teachers did not mention his work as a pioneering educator. This article fills in that gap.

It sounds like he is an unsung hero.